Merrymount Colony (1624-1630 CE) was a settlement first established in New England as Mount Wollaston in 1624 CE but renamed Mount Ma-re (referred to as Merrymount) in 1626 CE by the lawyer, writer, and colonist Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE), best-known, primarily, from his book New English Canaan (a treatise on the Native Americans of the region, natural history, and satiric critique of his colonist neighbors) and the work Of Plymouth Plantation by William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE), second governor of Plymouth Colony, in which he is referred to as the “heathen” who established a “school of Atheism” at Merrymount.

Unlike Plymouth Colony, or the later Massachusetts Bay Colony, Merrymount was more of a trade center than a residential/agricultural community but, owing to Morton's liberal attitude toward religion, and the rapport he developed with the Native Americans, became (according to Morton) more successful and popular than its neighbors. Morton encouraged a celebratory atmosphere and, in 1627 CE, had an 80-foot (24 m) tall Maypole erected in the town square and, declaring himself the community's host, welcomed colonists and Native Americans to a days-long festival.

Bradford sent his militia's commander Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) to arrest Morton in 1628 CE, and he was deported back to England. He returned in 1629 CE, however, and again took up residence at Merrymount until he was again arrested and deported and Merrymount burned in 1630 CE. The story of the colony is given in a number of 17th-century CE sources, including those by Morton, Bradford, and John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The site of Merrymount is now a residential development in Quincy, Massachusetts, but the memory of the settlement as a progressive alternative to the Puritan or separatist models is still celebrated there occasionally by admirers of Morton in the present day.

Mount Wollaston Becomes Merrymount

Morton was employed as a lawyer by the merchant and investor Sir Ferdinando Gorges (l. c. 1565-1647 CE) in 1622 CE, went on a reconnaissance mission for him to North America, returning in 1623 CE, and was then sent back in 1624 CE on an expedition, led by Captain Richard Wollaston (d. 1626 CE) and comprised of 30 indentured servants, to establish a permanent colony for trade some 40 miles (64 km) away from Plymouth Colony. Plymouth Colony had a profitable fur trade established with the Native Americans of the region by this time and, based on Bradford's work, seem to have taken little notice of the new colony, named Mount Wollaston, at first.

In 1626 CE, according to Bradford, Wollaston took some of the indentured servants to Jamestown and hired them out to others. He died at some point the same year and, also according to Bradford, Morton convinced the servants left at Mount Wollaston to rebel against the second-in-command Wollaston had left there (a man named Fitcher), and join him in a venture in which they would all share the profits equally. Once this was accomplished, Morton renamed the settlement Mount Ma-re (from the French mer for “sea” as it was near the coast but a play on “merry”), later known as Merrymount.

Merrymount & Plymouth Conflict

The Plymouth Colony had been founded in 1620 CE by the passengers of the ship Mayflower, who were both religious separatists and Anglicans. The colony was governed according to the Mayflower Compact, signed by the majority of the men in November 1620 CE, establishing a democratic form of government, elected officials, and rule of law. The separatists and Anglicans lived together peacefully at Plymouth, each respecting the other's rights and beliefs, and worked together in establishing a treaty with the Wampanoag Confederacy under their chief Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661 CE) in March of 1621 CE. Once Merrymount came to their attention, Bradford has nothing good to say about the new colony - which departed from his own vision dramatically - devoting a long passage to criticizing Morton and his group. After Morton had removed Fitcher, Bradford writes:

They then fell to utter licentiousness and led a dissolute and profane life. Morton became lord of misrule and maintained, as it were, a school of Atheism. As soon as they acquired some means by trading with the Indians, they spent it in drinking wine and strong drinks to great excess – as some reported, 10 pounds worth in a morning! They set up a Maypole, drinking and dancing about it for several days at a time, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together like so many fairies – or furies, rather – to say nothing of worse practices. It was as if they had revived the celebrated feasts of the Roman goddess Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians. Morton, to show his poetry, composed sundry verses and rhymes, some tending to lasciviousness and others to the detraction and scandal of some persons, affixing them to his idle, or idol, Maypole. They changed the name of the place and instead of calling it Mount Wollaston, they called it Merry Mount, as if this jollity would last forever…In order to maintain this riotous prodigality and excess, Morton, hearing what profit the French and the fishermen had made by trading guns, powder, and shot to the Indians, began to practice it hereabouts, teaching them how to use them. Having instructed them, he employed some of them to hunt and fowl for him, until they became far more able than the English, owing to their swiftness on foot and nimbleness of body, being quick-sighted, and knowing the haunts of all sorts of game. With the result that, when they saw what execution a gun would do, and the advantage of it, they were mad for them and would pay any price for them, thinking their bows and arrows but baubles in comparison. (Book II. ch. 9.)

Merrymount could not have been more different from Plymouth in every way. Morton abolished any sort of hierarchy or leadership, referring to himself as “Mine Host” and seeming to consider himself as just another among equals. There is no mention made of Merrymount forming a treaty with the Native Americans because Morton would not have thought one necessary as he treated the natives as equals and found them more honorable than the Christian colonists he had engaged with in the region. Although alcohol was certainly used at Plymouth, it was done so in moderation while, at Merrymount, the people seem to have enjoyed strong drink as often as possible.

According to Morton, the Plymouth Colony's leaders (and later those of Massachusetts Bay Colony) objected to his use of the Book of Common Prayer, his “revels” which included natives and colonists, and his success in the fur trade. Morton downplays Bradford's charge of regular “licentiousness”, claiming they only had a celebration of Mayday:

[After re-naming the colony Merrymount], and being resolved to have the new name confirmed for a memorial to after-ages, [the inhabitants] did devise amongst themselves to have it performed in a solemn manner, with revels, and merriment after the old English custom; prepared to set up a Maypole upon the festival day of [Mayday] and therefore brewed a barrel of excellent beer and provided a case of bottles to be spent, with other good cheer, for all comers that day. And, because they would have it in a complete form, they had prepared a song fitting to the time and present occasion. And upon Mayday, they brought the Maypole to the place appointed, with drums, guns, pistols, and other fitting instruments for that purpose, and there erected it with the help of savages that came thither of purpose to see the manner of our revels. A goodly pine tree of 80-foot-long was reared up, with a pair of buck's horns nailed on somewhat near unto the top of it; where it stood as a fair sea-mark for directions, how to find out the way to Mine Host of Ma-re Mount. (Book III. ch. 14.)

Morton himself makes no mention of selling guns and ammunition to natives but, according to Bradford, this was the primary cause of the conflict:

Morton, having taught them [the natives] the use of guns, sold them all he could spare, and he and his associates determined to send for large supplies from England, having already sent for over a score by some of the ships. This being known, several members of the scattered settlements hereabouts agreed to solicit the settlers at [Plymouth Colony], who then outnumbered them all, to join with them to prevent the further growth of this mischief and to suppress Morton and his associates. (Book II. ch. 9.)

Bradford then wrote to Morton demanding he stop selling guns to the natives but Morton refused, claiming there was no law against it. The later writer Charles Francis Adams, Jr. (l. 1835-1915 CE), who edited and published the 19th-century CE edition of Morton's New English Canaan, notes how the lawyer Morton "at least showed himself in this dispute better versed in the law of England than those who admonished him" as there was no law against selling arms to the natives, only a proclamation against it by King James I (r. 1603-1625 CE) and, since he had recently died, the power of the proclamation – which had never actually been law – died with him (Adams, 26). Morton, Adams points out, may have recognized it would be good policy to abide by his neighbors' request and maintain good relations, but this sort of consideration does not seem to have mattered to him.

Arrest & Deportation

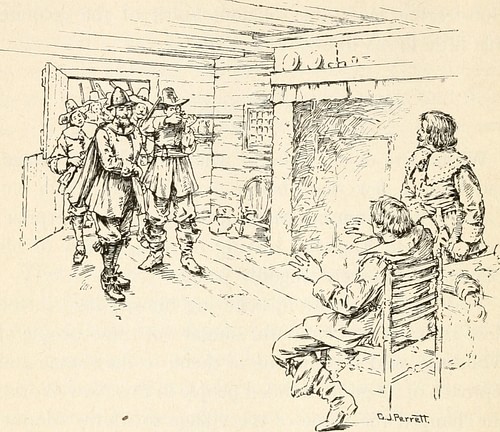

After Morton refused his demands, Bradford sent Myles Standish to arrest him in 1628 CE. Bradford writes:

[Morton] defended himself stiffly, closed his doors, armed his associates, and had dishes of powder and bullets ready on the table; and if they had not been over-armed with drink, more harm might have been done. They summoned him to yield, but they got nothing but scoffs from him. At length, fearing [Standish and his men] would wreck the house, some of his crew came out, intending not to yield but to shoot, but they were so drunk that their guns were too heavy for them. [Morton] himself, with a carbine, overcharged and almost half filled with powder and shot, tried to shoot Captain Standish; but he stepped up to him and put aside his gun and took him. No harm was done on either side. (Book II. ch. 9.)

Morton gives a different version of events:

The Separatists [of Plymouth Colony], envying the prosperity and hope of the plantation at Ma-re Mount (which they perceived began to come forward, and to be in a good way for gain in the Beaver trade), conspired together against Mine Host especially (who was the owner of that plantation) and made up a party against him and mustered up what aid they could, accounting of him as of a great monster. [They found Mine Host at Wessagussett and] because Mine Host was a man that endeavored to advance the dignity of the Church of England, which they (on the contrary part) would labor to vilify with uncivil terms, inveighing against the sacred Book of Common Prayer, and Mine Host that used it in a laudable manner amongst his family, [arrested him]…Much rejoicing was made that they had gotten their capital enemy, whom they purposed to hamper in such sort that he should not be able to uphold his plantation at Ma-re Mount. [They began to drink to celebrate, got drunk, and fell asleep, after which Mine Host escaped to Merrymount]. The word which was given with an alarm was O he's gone, He's gone, what shall we do, He's gone? The rest (half asleep) started up in a maze, and like rams, ran their heads one at another full-butt in the dark. Their grand leader Captain Shrimp [Standish] took on most furiously and tore his clothes for anger to see the empty nest and their bird gone. (Book III. ch. 15.)

Morton goes on to relate how Standish and his men then tracked him to Merrymount where he agreed to surrender on the condition that no one – especially himself – was harmed; after this was agreed to and he had come out of his house, however, he was attacked, bound, and taken away. He was marooned on the Isle of Shoals off the coast without provisions and only survived through the intercession of Native Americans who brought him food and cared for him until he took ship for England.

Morton returned in 1629 CE and was again at Merrymount when he was arrested by the Puritan (and future governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony) John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), who chopped down the Maypole and burned Morton's house and the settlement. Morton and Bradford give vastly different views of this event, as with any other, with Morton claiming innocence on his part, and Bradford triumphing in the destruction of the settlement which had come to be known as Mount Dagon (a reference to the biblical account of the statue of the Canaanite deity Dagon falling before the Ark of the Covenant as told in I Samuel 5:1-5). Morton was deported again after the colonists found a ship that would carry him, and Merrymount Colony was finished.

Conclusion

Morton was not finished with Merrymount, however, and initiated a lawsuit to have the charter of Massachusetts Bay Colony revoked. He eventually turned the briefs from the suit (which came to nothing) into the early drafts of the book that would become New English Canaan (published 1637 CE). Morton returned to New England in 1642 CE and was jailed in Boston by 1644 CE. He was finally released due to poor health (and lack of any evidence of the charge that he was a “Royalist Agitator”) and died in present-day York, Maine in 1647 CE.

New English Canaan, Merrymount, and Morton were more or less vilified for the next century by various authors. Even Adams, who edited and published the book in 1883 CE was not an admirer and only became interested in Morton because he owned the land which included the former site of the settlement. Although a number of 19th-century CE writers took a more positive view of Merrymount and its host, author Nathaniel Hawthorne (l. 1804-1864 CE), in his short story The May-Pole of Merry Mount (published 1832 CE) seems to mark the turning point.

The story is a fictionalized version of Endicott's arrival, the destruction of the Maypole, and the burning of the settlement. Morton does not appear by name but is represented by the figure of the officiant (“the flower-decked priest”) at the wedding ceremony of two young people who, though at first happy, lose their joy at the thought that all could change for them suddenly just before Endicott and his band of Puritans arrive. Endicott cuts down the Maypole, orders the people of Merrymount to be whipped, sparing the couple and priest for the moment, and orders a dancing bear, who was among the group, shot in the head. The young couple is led away by the Puritans in the end and “with the setting sun, the last day of mirth had passed from Merry Mount” (48). The story is regularly viewed as a striking juxtaposition between the “gloom” of the Puritans of New England and the “jollity” of the colonists of Merrymount, but not every 19th-century CE writer followed Hawthorne's lead or agreed with him on this. Morton and his colony continued to be viewed negatively, for the most part, even after Hawthorne's story was republished in his popular Twice-Told Tales and reached a wider audience in 1837 CE.

By the 20th century CE, however, Merrymount and its host were viewed more or less positively as Hawthorne's view gained wider acceptance, and in the last 50 years, this opinion has been adopted by more scholars. Scholar Philip Howard Gray published his essay Thomas Morton as America's First Behavioral Observer (in New England 1624-1646) in 1987 CE, demonstrating how Morton has been neglected by scholarship or misrepresented in texts which rely on Bradford's account, and others have since argued the same. The release of the scholarly edition of New English Canaan by Thomas Morton of “Merrymount” Text & Notes by Jack Dempsey in 2000 CE has generated more interest in the colony and its host, and this trend in scholarship, as well as the general shift toward a more positive view of Merrymount, will most likely only continue.