Mesopotamian religion was central to the people's lives. Humans were created as co-laborers with their gods to hold off the forces of chaos and to keep the world running smoothly. As in ancient Egypt, the gods were honored daily for providing humanity with life and sustenance, and people were expected to give back through works that honored the gods.

It was understood that, in the beginning, the world was undifferentiated chaos and that order was established by the gods. The gods had separated the sky from the earth, the land from the water, saltwater from freshwater, plants from animals, and this order needed to be maintained. As the gods had many different responsibilities, humans were created to help them in the operation of the world. The meaning of life, therefore, was to live in accordance with this understanding, and so one's daily life would be a form of worship.

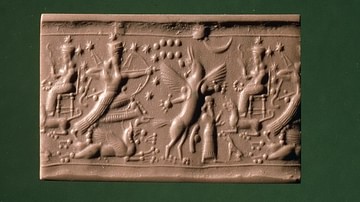

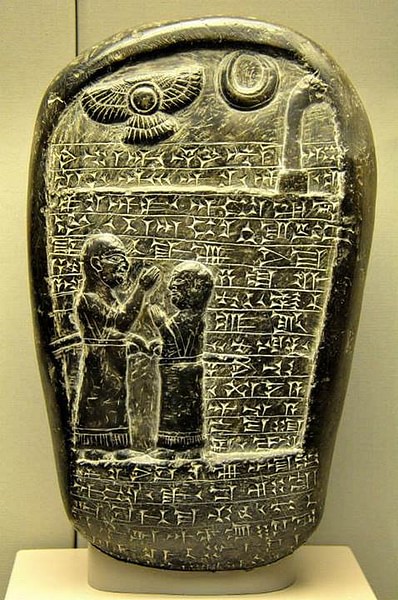

Every city had a temple complex clearly visible from afar for its ziggurat, the monumental architecture most closely associated with Mesopotamia, which was usually topped by a temple or shrine, elevating the officiant closer to the gods. The gods were understood as inhabiting their own realm but also living in the temple, in the statues created in their images in every city. This belief was already firmly in place by the time of the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) and developed fully during the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE).

Although Mesopotamian religion changed in focus and the names of the deities over the centuries, the central understanding of the relation between humanity and the gods did not. As late as c. 650 CE, the people of Mesopotamia still adhered to the belief that they were the gods' coworkers who assisted in the maintenance of order. This paradigm only changed after 651 CE with the invasion of the Muslim Arabs and the new monotheistic religious model of Islam.

Mesopotamian Creation Myth

According to the Babylonian creation myth, the Enuma Elish, (meaning 'When on High') life began after an epic struggle between the elder gods and the younger. In the beginning, there was only water swirling in chaos and undifferentiated between fresh and bitter. These waters separated into two distinct principles: the male principle, Apsu, which was freshwater, and the female principle, Tiamat, saltwater. From the union of these two principles, all the other gods came into being.

These younger gods were so loud in their daily concourse with each other that they came to annoy the elders, especially Apsu, and, on the advice of his Vizier, he decided to kill them. Tiamat, however, was shocked at Apsu's plot and warned one of her sons, Ea, the god of wisdom and intelligence. With the help of his brothers and sisters, Ea put Apsu to sleep and then killed him. Out of the corpse of Apsu, Ea created the earth and built his home; though, in later myths 'the Apsu' came to mean the watery home of the gods or the realm of the god Enki.

Tiamat, upset now over Apsu's death, raised the forces of chaos to destroy her children herself. Ea and his siblings fought against Tiamat and her allies, her champion, Quingu, the forces of chaos, and Tiamat's creatures, without success until, from among them, rose the great storm god Marduk. Marduk swore he would defeat Tiamat if the gods would proclaim him their king. This agreed to, he entered into battle with Tiamat, killed her, and from her body, he created the sky. He then continued on with the act of creation to make human beings from the remains of Quingu as helpmates to the gods.

According to scholar D. Brendan Nagle:

Despite the gods' apparent victory, there was no guarantee that the forces of chaos might not recover their strength and overturn the orderly creation of the gods. Gods and humans alike were involved in the perpetual struggle to restrain the powers of chaos, and they each had their own role to play in this dramatic battle. The responsibility of the dwellers of Mesopotamian cities was to provide the gods with everything they needed to run the world. (11)

Temples, Gods & Worship

The gods, in turn, took care of their human helpers in every aspect of their lives. From the most serious concerns of praying for continued health and prosperity to the simplest, the lives of the Mesopotamians revolved around their gods and so, naturally, the homes of the gods on earth: the temples. People did not attend regular worship services; the veneration of the gods was the business of the clergy. People prayed to and honored the gods at personal shrines, offered sacrifices at the temple, and gathered for festivals in the courtyard of the temple complex but did not enter the temple for any kind of service. Priests interceded for the people with the gods and delivered divine messages for the community.

Every city had at its center the temple of the patron deity of that city honored through the construction of a ziggurat. Eridu (founded c. 5400 BCE), home of the god Enki, was regarded as the first city in the world where the gods established order, but there were many sacred sites and centers. Among the most famous holy cities was Nippur where the god Enlil legitimized the rule of kings and presided over pacts. So important a center was Nippur that it survived, intact, into the Christian and then the Muslim periods and continued, until 800 CE, as an important religious center for those new faiths.

Among the most popular gods of the Mesopotamian Pantheon (which numbers over 3,600 deities) were:

- Anu – the Sumerian sky god

- Assur/Ashur – supreme god of the Assyrians

- Enlil – Sumerian lord of the air, Anu's son, king of the gods

- Enki – Sumerian god of wisdom

- Ereshkigal – Sumerian goddess of the underworld

- Gula – Sumerian goddess of health and healing

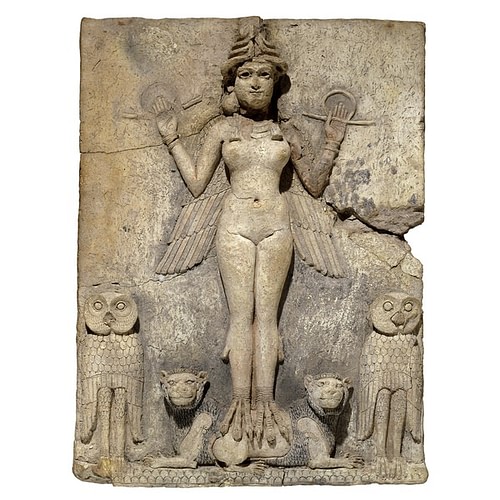

- Inanna – Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and war; later known as Ishtar

- Marduk – Babylonian king of the gods

- Nabu – Babylonian god of writing, Marduk's son

- Nanna – Sumerian god of the moon

- Nanshe – Sumerian goddess of social justice

- Nergal – Sumerian god of war

- Ninhursag – Sumerian Mother Goddess

- Ninkasi – Sumerian goddess of beer and brewing

- Nisaba – Sumerian goddess of writing and accounts

- Utu-Shamash – Sumerian god of the sun

Among these were the Seven Divine Powers, the oldest Sumerian deities:

- Anu

- Enki

- Enlil

- Inanna

- Nanna

- Ninhursag

- Utu-Shamash

The patron god or goddess of a city had the largest temple, but there were smaller temples and shrines to other gods throughout any urban center. The god of a particular temple was thought to literally inhabit that building and most temples were designed with three rooms, all heavily ornamented, the innermost being the room of the god or goddess where that deity resided in the form of his or her statue. Every day the priests of the temple were required to tend to the needs of the god. According to Nagle:

Daily, to the sound of music, hymns, and prayers, the god was washed, clothed, perfumed, fed and entertained by minstrels and dancers. In clouds of incense, meals of bread, cakes, fruit and honey were set before the deity, along with offerings of beer, wine and water ... On feast days the statues of the deities were taken in solemn procession through the courtyard [and] the streets of the city accompanied by singing and dancing. (12)

The gods of every city were offered this same respect and, it was believed, they needed to make the rounds of the city at least once a year in the same way a good ruler would ride out from his palace to inspect his territory regularly.

The gods could even visit each other on occasion as in the case of the god Nabu whose statue was carried once a year from Borsippa to Babylon to visit his father Marduk. Marduk, himself, was honored greatly in this same way at the New Year Festival in Babylon when his statue was carried out of the temple, through the city, and to a special little house outside the city walls where he could relax and enjoy some different scenery. Throughout this procession, the people would chant the Enuma Elish in honor of Marduk's great victory over the forces of chaos.

Mesopotamian Underworld

The Mesopotamians not only revered their gods but also the souls of those who had gone on to the underworld. The Mesopotamian paradise (known as Dilmun to the Sumerians) was the land of the immortal gods and was not given the same sort of attention the underworld received. The Mesopotamian underworld (Kurnugia, Irkalla, or Allatu) where the souls of departed humans went, was a dark and dreary land from which no one ever returned, but even so, a spirit who had not been honored properly in burial could still find ways to slip out and inflict misery on the living.

As the dead were often buried under or near the home, each house had a small shrine to the dead inside (sometimes a chapel built onto the existing homes of the more affluent, as seen at Ur) where daily sacrifices of food and drink were made to the spirits of the departed. Should one fail in one's duties to the dead, one could expect to be haunted, and ghosts in ancient Mesopotamia were understood as a fact of life like any other. If, however, one had done one's duty to the departed and honored the gods and others in the community, but still suffered some unfortunate fate or string of bad luck, a necromancer was consulted to see if one had unknowingly offended the spirits of the dead in some way.

The famous Babylonian poem Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi of c. 1700 BCE (known as "the Sumerian Job" owing to its similarity to the biblical Book of Job) makes mention of this when the speaker, Tabu-Utul-Bel (known in Sumerian as Laluralim) in questioning the cause of his suffering, says how he consulted the necromancer, "but he opened not my understanding." Like the Book of Job, the Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi asks why bad things happen to good people, and, in Laluralim's case, asserts that he did nothing to offend fellow man, gods, or spirits to merit the misfortune he is suffering.

Divination

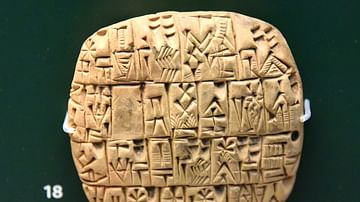

Divination was another important aspect of Mesopotamian religion and was developed to a high degree. A clay model of a sheep's liver, found at Mari, indicates in great detail how a diviner was to go about interpreting the messages found in that organ. To the Mesopotamians, divination was a scientific method of interpreting and understanding the messages from the gods in earthly contexts. If a certain type of bird acted in an unusual way, it could mean one thing, while if it acted in another, the gods were saying something different.

A man suffering from certain symptoms would be diagnosed by a diviner in one way while a woman with those same symptoms in another, depending on how the diviner read the signs presented. The great rulers of the land had their own special diviners (as later kings and generals would have their personal doctors), while the less affluent had to rely on the care provided by the local diviner.

Influence of Mesopotamian Myths

The people of Mesopotamia relied on their gods for every aspect of their lives, from calling on Kulla, the god of bricks, to help in the laying of the foundation of a house, to petitioning the goddess Lama for protection, and so developed many tales concerning these deities. The myths, legends, hymns, prayers, and poems surrounding the Mesopotamian gods and their interaction with the people introduced many of the plots, symbols, and characters which modern-day readers are acquainted with, including:

- the story of the fall of man (The Myth of Adapa),

- the tale of the Great Flood (The Atrahasis, Eridu Genesis, Gilgamesh),

- the tree of life (Inanna and the Hulappu Tree),

- the tale of a wise man/prophet taken up to heaven (The Myth of Etana),

- the story of creation (The Enuma Elish),

- the quest for immortality (The Epic of Gilgamesh),

- the dying and reviving god figure (a deity who dies or goes into the underworld and returns to life or the surface of the world to in some way benefit the people) who is famously depicted through Inanna's Descent to the Underworld.

These tales, among many others, became the basis for later myths in the regions the Mesopotamians traded and interacted with, most notably the land of Canaan (Phoenicia), whose people, in time, would produce the narratives which now comprise the scriptures known as the Old and New Testaments of the Bible.

Conclusion

Mesopotamian religion is understood as among the oldest in the world. The belief system of the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 7000 to c. 600 BCE) is possibly older, but, as their script has not yet been deciphered, this is unclear. The understanding of the meaning of life as maintaining order in accordance with the divine also informed ancient Egyptian religion, but the claim that Mesopotamian beliefs influenced Egyptian religious concepts has been challenged and continues to be debated.

As noted, the religious beliefs and practices of Mesopotamia continued for thousands of years, its central understanding unchanged, even with the rise of monotheistic Zoroastrianism after c. 550 BCE, until the advent of Islam in the region. Monotheistic Islam, like Judaism and Christianity, removed the gods from the world of humanity and set a single, all-powerful deity high in the heavens. As there was no longer a reason to continue the care and upkeep of the statues and temples of the gods of Mesopotamia, they fell into ruin as the old faith was slowly abandoned.