Mesrop Mashtots (360/370 - c. 440 CE) invented the Armenian alphabet in 405 CE. Besides greatly increasing levels of literacy in the country, the language permitted ordinary people to read the Bible for the first time, thus helping to further spread and entrench Christianity in Armenia, which was the original intention behind the script's invention. For these achievements Mashtots (Mastoc) was made a saint of the Armenian Church.

Early Life

Mashtots came from a family of modest status living in Hatsekats, a provincial town in the Taron province of ancient Armenia. After an education focussed on Greek literature and an early career in the military, Mashtots served at the Armenian royal court before joining the Christian church and working as a missionary in the southeast of Armenia. It was then that the young evangelist realised how important it could be for his conversion rates if the people could read about the Gospel message in their own language, spoken Armenian not having, at that time, a written form. Christian texts were useless to common people as they were written in either Greek or Syriac, both of which only highly educated people could read. To do anything useful, though, Mashtots needed a powerful sponsor and state backing.

Creating a New Alphabet

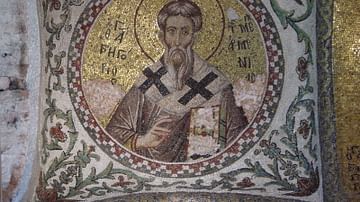

Fortunately for Mashtots, the founder of the ruling Arsacid dynasty, Tiridates the Great (r. c. 298 - c. 330 CE), had converted to Christianity in 301 CE thanks to the efforts of Saint Gregory the Illuminator (c. 239 - c. 330 CE). Tiridates' successors were equally keen on spreading Christianity, especially as it reinforced the role of the monarch in the state as God's representative, and allowed the Arsacids to persecute and confiscate the property of any lingering adherents to the old pagan traditions. The reigning Arsacid monarch, then, Vrampshapuh (r. 392-415 CE), was willing to patronise Mashtots' project. Another supporter was the head bishop of the Armenian church, the Catholicos Sahak the Great (387-428 CE). Both men saw the value of enlightening the people and at the same time unifying them and creating a greater spirit of nationhood. Finally, the Christian faith in Armenia was far from secure and was continuously threatened by the religion of the neighbouring Persia.

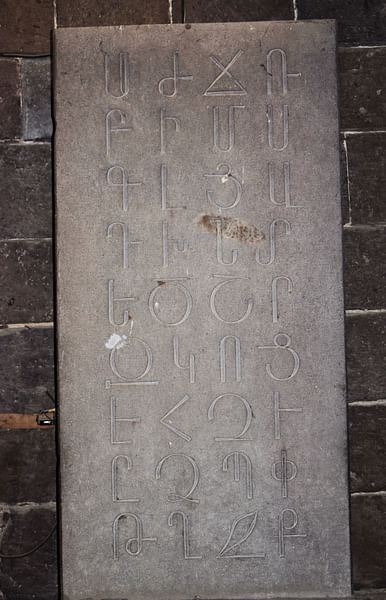

Mashtots began his task by researching possible existing languages which might most easily be adapted for his purpose. For this, he visited Edessa in northern Syria, a great centre of culture and learning, especially Christian scholarship. Disappointed in his quest, Mashtots decided that nothing short of a whole new alphabetic script was required. Relocating to Samosata, a Hellenized city in western Armenia, Mashtots discovered that the link between the Greek and Armenian languages could be exploited to create a coherent and practical script. Assisted by Rufinus, a Greek calligrapher, Mashtots compiled his alphabet of 36 symbols (28 consonants and 8 vowels) to capture the phonetic sounds of Armenian. The traditional date for the finished product is 405 CE, and it remains in use today with only two symbols added in later centuries to express sounds imported from foreign languages.

Mashtots' new alphabet mixed 21 Greek letters with 15 new phonemes. The Historical Dictionary of Armenia gives the following technical description of the complexity of the language:

Classical Armenian was a highly inflected language, with an elaborate system of declensions that retained all seven Indo-European noun cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, locative, ablative, and instrumental. In this and other respects, the grammar of classical Armenian bears similarities with that of Classical Greek. (393)

To help people get to grips with the new system Mashtots ordered the letters of the alphabet, when possible, according to the Greek alphabet and put them into harmonious clusters of three. The linguist then set about testing the system on friends and pupils to see which symbols proved more troublesome in mastering. His efforts were clearly worthwhile given the speed with which the new alphabet was picked up across Armenia. Not only helping to increase literacy and usher in a golden period of Armenian literature, it was another important factor in unifying the Armenian people, cementing their identity and sense of nationhood in what was still a young state.

Translating the Bible

Mashtots' work was not finished there, though. Now he had to put his creation to the purpose for which it was really invented: to spread the Christian message. Realising that he could not do this alone, the scholar set about assembling a trained team of linguists who were sent off to various cities to learn Greek or Syriac and who were then given the task of translating canons of the early church councils, liturgies, patristic texts and any other sources of value. Mashtots and the bishop Sahak assumed personal responsibility for the really big project: translating the Bible. Getting themselves an official copy from Constantinople, they cross-referenced it with other versions in Greek and Syriac to produce their definitive version in Armenian. The opening line of the Armenian Bible chosen by Mashtots was from the Proverbs of Solomon: “That men may know wisdom and instruction”.

Later Life & Legacy

Mashtots did not limit himself to translation work but also produced brand new literature in his brand new script. The scholar composed many hymns and homilies, amongst other works. In the first biography of Mashtots (and the first Armenian biography to be written), titled The Life of Mashtots (Vark Mashtotsi) and written by his pupil Koriun, the scholar is credited with inventing the Georgian and Albanian alphabets.

Mesrop Mashtots died in the Armenian capital of Vagharshapat on 17 February 439 (or 440 CE). He was buried in Oshakan which became a site of pilgrimage thereafter, especially following his raised status as a saint of the Armenian Church. Mesrop Mashtots continues to be revered today, too, by modern Armenians as here explained by the political historian R. Panossian:

The celebration of the alphabet and the literary work of the fifth century is sanctioned by the Armenian church as an official holiday (in October) called Surb Tarkmanchats (Holy Translators). It is noted both by the church and the laity in Armenia and in the diaspora as a celebration of Armenian literature and books. (46)

Saint Mashtots' work continues to live on today as, while the lower case of modern Armenian is based on the medieval script, the upper case of the alphabet he invented 16 centuries ago is still in use today.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.