Michael IV the Paphlagonian was Byzantine emperor from 1034 to 1041 CE. He had an affair with Empress Zoe, then married her and was crowned emperor after the death of her first husband, Romanos III. He ran a competent regime that kept the status quo in the Byzantine Empire, although he achieved no conquests of note.

Rise to Emperor

Michael came from a family of money changers from the region of Paphlagonia in Anatolia, whose residents had a bad reputation in Constantinople. His brother John, a eunuch who had become an influential person at the Byzantine court under Basil II, introduced Michael to Empress Zoe (r. 1028-1050 CE), who was at that time ruling with her first husband, Romanos III Argyros (r. 1028-1034 CE). John was called the Orphanotrophos, literally the director of an orphanage, although it had gained a broader meaning as someone with large tax exemptions. Soon after meeting, Zoe and Michael began an affair.

According to contemporary historian Michael Psellos, Michael was a “finely-proportioned young man, with the fair bloom of youth in his face, as fresh as a flower, clear-eyed, and in very truth red-cheeked,” but he was also an epileptic (Psellus, 49). Shockingly, Romanos was not jealous and even treated Michael with sympathy due to his epilepsy. Romanos died in his bath on December 10 or 11, 1034 CE, and although no foul play was found, it was rumored that Zoe and Michael had poisoned him. At some point over the next few years, Michael stopped sleeping with Zoe and started to give alms to the poor, built monasteries, and engaged in public works to benefits monks and the destitute. This may have just been to boost popular support, but the combination of these acts also may signify a desire to make up for previous sins.

After Romanos died, Zoe immediately asked Patriarch Alexios to marry her and Michael. Alexios was concerned because Orthodoxy required women to grieve for a whole year before marrying again, and there was the well-known pre-existing affair between the two. Alexios eventually acquiesced, citing the importance for the Byzantine Empire, although a bribe of 50 gold pounds from John the Orphanotrophos certainly did not hurt.

Domestic Affairs

After Michael was married, he was crowned emperor and publicly acclaimed as such, helping legitimize his rule, which was also helped by the fact that Romanos III had not been very popular. Although Michael was now emperor, he left most of the administrative tasks in the hands of his brother, John. According to Psellos, John was an exacting and hardworking micromanager (Psellus, 62). Michael did not even spend that much time in Constantinople: unusually for emperors, he spent significant time in the provinces, especially in Thessalonica, where he believed there was a potential cure for his epilepsy.

But John and Michael also promoted their many brothers to positions of power as well, which caused the old elite to grow restless. The leading military magnate of this time, Constantine Dalassenos, was tricked into coming to Constantinople and kept there by John to prevent him from rebelling. Meanwhile one of Michael's brothers, Niketas, was now the doux, or duke, of Antioch, but when he arrived he was locked out of the city until he agreed to a general amnesty for the citizens who had killed an oppressive tax collector a few weeks earlier. Niketas agreed, only to execute the ringleaders upon entering the city. He then sent the remaining culprits to Constantinople, claiming they were in cahoots with Constantine Dalassenos. This led Michael to arrest Constantine and his son-in-law, the future Constantine X Doukas (r. 1059-1067 CE). Michael did not face any rebellions by the landed magnates of the Byzantine Empire for the rest of his reign, although in 1038 CE he did send the entire Dalassenos family into exile.

Although Michael had married into the ruling Macedonian Dynasty, there was no doubt that the Macedonian Dynasty, not Michael's upstart family from Paphlagonia, held the right to rule. However, Zoe and her sister, Theodora, were the only two surviving members of the Macedonian Dynasty, and both were over 50, meaning the dynasty would die with them. To set up a Paphlagonian dynasty, Michael had Zoe formally adopt his nephew, also named Michael (the future Michael V, r. 1041-1042 CE), and appointed him caesar, or heir to the throne.

Foreign Affairs

Although Byzantium still had substantial military power, during Michael's reign the Byzantine Empire was mostly on the defensive. Pecheneg raids across the Danube devastated parts of the Balkans, one group even reaching as far as Thessalonica, although they appear to have stopped after 1036 CE, signaling a possible truce. Local Muslim emirs attacked Edessa in 1036 and 1038 CE, the 1036 CE siege being ended only through the timely intervention of Byzantine forces from Antioch. The Georgian army attacked the eastern provinces in 1035 and 1038 CE, although in 1039 CE the Georgian general Liparit invited the Byzantines into Georgia to overthrow Bagrat IV and replace him with his half-brother, Demetre, and although the plot ultimately failed, it allowed the Byzantines to intervene in Georgia in the wars between Liparit and Bagrat for the next two decades. Michael also concluded a ten-year truce with the Fatimids, after which Aleppo ceased to be a major theater of war for the Byzantine Empire. In the Balkans, Michael cultivated client relationships with Serb lords, the zupans, to secure that flank as well.

The only aggressive theater of war during Michael's reign centered on Sicily. The Byzantine navy beat off Sicilian Arab ships attempting to raid the Aegean with the help of Varangian mercenaries under Harald Hardrada, the future King of Norway (r. 1046-1066 CE). Sicilian Arab raids had plagued Byzantine Italy even after the katepano, or senior military commander, Boioannes re-established Byzantine rule in Southern Italy between 1018 and 1028 CE. In the 1030s CE, a civil war broke out on Sicily between Ahmad al-Akhal and his brother, Abu Hafs. Ahmad made a treaty with the Byzantines in 1035 CE, being granted the honorific title of magistros and sending his son to Constantinople. This seeming subservience to the Byzantines led the North African Zirids to invade under their emir, 'Abd Allah. Although Ahmad called on the Byzantines, he was killed in battle.

A Byzantine army from Italy invaded in 1038 CE, as did a substantial fleet from Constantinople headed by Stephanos, the father of the caesar Michael, and the accomplished general George Maniakes, which included the Varangian Guard under Hardrada. Maniakes crushed the Arab forces at Rometta and conquered eastern Sicily, including the old Roman capital of Syracuse. 'Abd Allah escaped, however, and Maniakes blamed Stephanos, yelling at him and even whipping his head. Stephanos complained to Michael, and Michael replaced George with Basil Pediadites and arrested him. After George was removed, however, the Byzantines started to lose in Sicily, and by 1042 CE all of George's conquests were lost. No Byzantine attempt to recover Sicily would ever take place again.

The Bulgarian Rebellion & Michael's Final Year

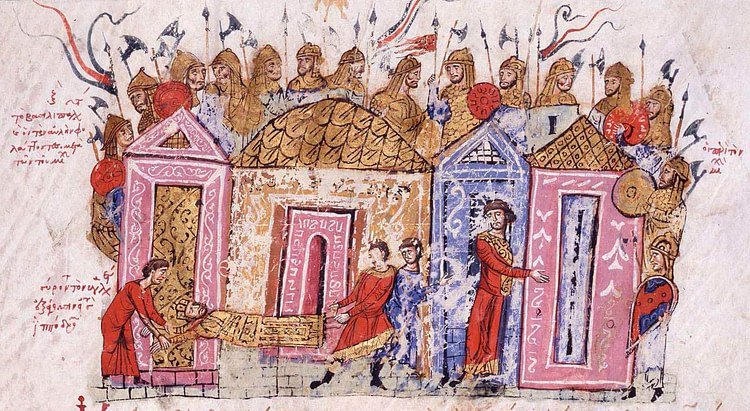

Part of the reason for the loss of Sicily was that Michael had to pull troops from Sicily to meet a massive Bulgarian uprising much closer to home. The Bulgarians possibly rose up because John the Orphanotrophos required Bulgarians to pay tax in coin, rather than in kind as Basil II had allowed after conquering Bulgaria. No doubt a sense of national identity did play some role in the rebellion too. This rebellion was led by Deljan, who said he was a grandson of Samuel (r. 997-1014 CE), the former Bulgarian tsar and great longtime adversary of Basil II (r. 976-1025 CE), and declared himself Tsar Petar II of Bulgaria. Tihomir also led a rebellion of Bulgarian troops at Dyrrachium, but Tihomir was tricked and killed by Deljan, and his forces were incorporated into Deljan's army. Deljan then marched on Thessalonica, forcing Michael, who was stationed there, to flee to Constantinople, even abandoning the imperial tent. At Thessalonica, Manuel Ibatzes, son of Samuel's leading general, also joined the rebellion. In the coming months, Deljan sent troops to take Dyrrachium and Thebes, and the theme of Nikopolis joined Bulgaria willingly against the Byzantine Empire.

Alusian, the son of Ivan Vladislav, the last Tsar of Bulgaria (r. 1014-1018 CE) then joined Deljan, who gave him an army to attack Thessalonica. The Byzantines defeated Alusian and returned to Deljan, but both were highly suspicious of the other, and Alusian eventually blinded Deljan after inviting him to a banquet. In 1041 CE, Michael marched against the Bulgarian rebels, despite having contracted dropsy. Alusian agreed to betray the Bulgarian rebels in exchange for money and titles. Michael's army then marched through the occupied territory, quashing the rebellion. Michael took Deljan in chains back to Constantinople and celebrated a triumph.

While Michael was popular, his family was not. Rebellions started to foment in Constantinople under the future patriarch Michael Keroularios and at the military camp of Mesmakta in Asia Minor, but both were snuffed out before they could begin. However, Michael had no more time to strengthen the position of his family before his death. At the end of 1041 CE, Michael was tonsured and became a monk. He refused to see Zoe as he lay dying, and he passed away on December 10, 1041 CE.

Michael's Legacy

Michael and his brothers had proven surprisingly capable for having started as nobodies from the backwaters of Paphlagonia, yet Michael's legacy was his nephew, Michael V (r. 1041-1042 CE), for whom that would not be true. Michael had kept Byzantine fortunes intact and had stopped the dangerous Bulgarian uprising, but he had failed to train a worthy successor to maintain and further the position of Byzantium.