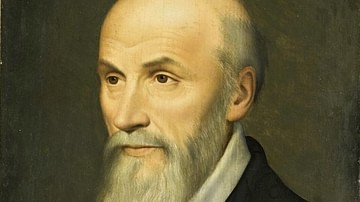

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a post-modernist French philosopher and is considered one of the most influential philosophers of modern times. Aside from his critiques of social institutions, his influence can be seen in both the humanities and social sciences. A central theme of Foucault's work is the relationship between power and knowledge, more specifically, how power controls and defines knowledge.

As an observer and critic of both the penal system and mental institutions, Foucault believed that "schools serve the same function as prisons and mental institutions — to define, classify, control and exploit people" (Despeyroux 78). He held that society and social institutions are controlled through relations of power. While some critics view him as being pessimistic, to Foucault, the value of philosophy, if organized according to his methods, is a means of changing the balance of authority over the individual through the exposure of the power structures intended to control us.

Life

Paul-Michel Foucault was born in Poitiers, France, on 15 October 1926, the second child of Anne Malapert and Paul Foucault, a prominent and wealthy surgeon and professor of anatomy. His father wanted the young Michel to follow in his footsteps and become a doctor, but claiming his ambitions were affected by World War II, Foucault thought otherwise. He entered the distinguished graduate school École Normale Supérieure in 1946, graduating in 1951 with degrees in philosophy and psychology. It was while he was a student that he allegedly made his first attempt at suicide, which, according to one historian, demonstrated a self-destructive tendency in his character (Oliver, 178).

After graduating, he left France to escape the conservative sexual mores of the post-war French culture. He chose, instead, to travel for several years, teaching in Sweden, Poland, and Germany.

He returned to France in 1960 and taught philosophy and psychology at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. He published his first book Madness and Civilization, an analysis of the treatment of madness in the Middle Ages and beyond.

In 1970, he was elected to the most prestigious Collège de France, but by the late 1970s, a disillusioned Foucault quit teaching and traveled the world until he died of an AIDS-related disease in 1984. Jeremy Stangroom in his The Great Philosophers wrote that Foucault lived his life as if he were driven by the need to "transcend both physical and cultural limits" (155)

Influences

Aside from the writings of the existentialist Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), Foucault found solace and inspiration in the works of the controversial German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Foucault wrote:

Nietzsche was a revelation to me. I felt that there was someone quite different from what I had been taught, I read him with great passion and broke with my life, left my job in the asylum, left France. I had the feeling I had been trapped.

(quoted in Despeyroux, 79)

While Foucault may have disagreed with other philosophers – e.g. Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud – he drew inspiration from Nietzsche. Nietzsche, like Foucault, challenged traditional philosophy.

Major Works

Michel Foucault's major works cover such topics as human sexuality, the systems of thought, and the penal system:

- Madness and Civilization (1961) – an analysis of the treatment of madness from the Middle Ages to the modern day

- The Birth of the Clinic (1963) – a history of the development of the clinic as a medical institution and the application of medical knowledge

- The Order of Things (1966) – an analysis of the history of human sciences

- Discipline and Punish (1975) – an analysis of the history and changes in the penal system

- The History of Sexuality (1976) – a multivolume analysis of the changing attitudes toward human sexuality in the Western world

Power & Knowledge

The Order of Things and Discipline and Punish, demonstrate how Foucault wanted to create a new direction for French philosophy. To accomplish this goal, he drew upon such academic disciplines as philosophy, history, psychology, and sociology. Through his understanding of the correlation between power and knowledge, he wanted to demonstrate how both power and knowledge interact to produce an individual or the self that is constituted as a knowing, knowable, and self-knowing subject in the relations of power and discourse. This new direction necessitates both a rethinking of the concept of power and an examination of the relationship between power and knowledge.

Foucault, like Nietzsche, argued that knowledge and power are inseparable; power and knowledge imply one another. Without power, there is no knowledge, and without knowledge, there is no power. To Foucault, power is more than just the ability of one person to persuade another person to do what he might otherwise not want to do.

According to Philip Stokes in his Philosophy: The Great Thinkers, Foucault's intent throughout his work was to focus on what people generally consider to be knowledge – i.e. concepts such as reason, normality, and sexuality – concepts through which they can understand themselves. This rethinking can be difficult because these concepts do not evolve along a specific path of progress. Any new concept of knowledge can be difficult to define, for it means something totally different from one culture to another and from era to another. It changes in response to the needs of authority to control and regulate the behavior of the individual.

One of Foucault's aims as a philosopher was to expose the hidden structures of power. In order to find these hidden structures, he used genealogies – an idea taken from Nietzsche's On the Genealogies of Morals. This approach is a historical consideration of the notions of both truth and falsehoods as well as good and evil and how these concepts uphold power within a society. One of Foucault's genealogies is his Discipline and Punish. In it, he writes about an 18th-century public execution. This depiction of an execution illustrates a point of evolution from the methods of punishment that centered on the body to the more modern focus of punishment on the mind. This change reflects the development of what he called "the disciplinary society."

Modes of Objectification

Philosophy has long been intent on categorizing the human existence. Through categorizing the psychological, moral, and status of people, society could then be organized accordingly. Philosophers such as Karl Marx (1818-1883) contributed to this concept by his creation of such categories as proletariat and bourgeoisie. Foucault was the first philosopher to understand – albeit disagree with – this tendency and its consequences. He contended that in Western societies there are three modes of what he termed 'objectification', which serve as a way to treat people as objects, not human beings. These three modes are:

- dividing practices

- scientific classification

- and subjectification

In his explanations, it should be noted, that he drew many of his examples for all three modes from his experiences studying the penal system and mental institutions. Using a mental institution as an example, in dividing practices, people become objects by distinguishing and separating them from their peers on the basis of various distinctions such as normal and abnormal, sane and insane, or the permitted and the forbidden. It is through these dividing practices that people are categorized as mad, prisoners, or mental patients, identities through which they can recognize themselves and be recognized by others. In his book Madness and Civilization, Foucault analyzed how this mode was established as a specific category of human behavior allowing for people to be detained in institutions.

In the mode of scientific classification, distinctions are accomplished through the practices of the human and social sciences. For example, mental illness can be broken down into various categories. In the 19th century, the human body was treated as an object to be analyzed, labeled, and cured, which, according to Foucault, is still in practice today.

Lastly, subjectification is slightly different from the other two modes; it refers to the way in which people actively consider themselves as objects. The desire to understand oneself leads to one confessing one's innermost thoughts, feelings, and desires to oneself and others. Through these confessions, one learns how to change oneself. In the end, this process of the objectification of the individual is linked to a historical change in the nature of power and to developments in the areas of human and scientific knowledge.

Penal System & Madness

The nature of power has changed over the centuries. In the 17th century state power began to make its presence known in all areas of a person's life. With the arrival of industrial capitalism, the state moved away from an era of physical force as a kind of negative power and began to focus on the growth and health of its population. One area of change was in the penal system. In the West, the use of torture and physical abuse changed from the focus on the body to the soul or mind.

Foucault made reference to the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and his Panopticon where punishment was meant to be a method of reform. Bentham's idea employed supervision, observation, safety, and individualization. Under 24-hour watch, each person was isolated, alone, in his cell, watched by guards from a centrally located observation tower. However, the prisoner had no way of knowing if he was being watched, so he had to act as if he were, thereby becoming his own guard. Foucault believed it brought together power, knowledge, and the control of space into a simple, integrated disciplinary technology. Similarly, society exerts power to produce individuals who police themselves on matters of social, moral, physical, and psychological normality.

Conclusion

Foucault's concern with the matters of power and its control of knowledge was mirrored in his political activities and interest in such areas as LGBTQ+ rights, prison reform, mental health, and the welfare of refugees. Foucault's importance is that he showed how power operated; its ability to create human bodies, human subjects, and populations, which in various ways are surveyed, categorized, disciplined, and controlled.