The art of the Minoan civilization of Bronze Age Crete (2000-1500 BCE) displays a love of animal, sea, and plant life, which was used to decorate frescoes and pottery and also inspired forms in jewellery, stone vessels, and sculpture. Minoan artists delighted in flowing, naturalistic shapes and designs, and there is a vibrancy in Minoan art which was not present in the contemporary East. Aside from its aesthetic qualities, Minoan art also gives valuable insight into the religious, communal, and funeral practices of one of the earliest cultures of the ancient Mediterranean.

Inspirations

The Minoans, as a seafaring culture, were in contact with foreign peoples throughout the Aegean, as is evidenced by the Near East, Babylonian, and Egyptian influences in their early art but also in trade, notably the exchange of pottery and foodstuffs such as oil and wine in return for precious objects and materials such as copper from Cyprus and ivory from Egypt. Thus Minoan artists were constantly exposed to both new ideas and materials which they could use in their own unique art.

Minoan art was not only functional and decorative but could also have a political purpose, especially the wall paintings of palaces where rulers were depicted in their religious function, which reinforced their role as the head of the community. It is also important to remember that art objects were largely reserved for the ruling elite, who were in the considerable minority when compared to the rest of the population who were mostly farmers. Thus, costly art works became a means to emphasise differences in social and political status for those fortunate enough to own them.

Minoan Pottery

Minoan pottery went through various stages of development, and the first were the pre-palatial style known as Vasiliki with surfaces decorated in mottled red and black and Barbotine wares with decorative excrescences added to the surface. Next came polychrome Kamares ware. Probably originating from Phaistos and dating from the Old Palace period (2000 BCE - 1700 BCE), its introduction was contemporary with the arrival of the pottery wheel in Crete. The distinctive elements of Kamares pottery are lively red and white designs on a black background. Geometric forms are common but there are also impressionistic fish and polyps as well as abstract human figures. Sometimes, shells and flowers were also added to the vessel in relief. Common forms are beaked jugs, cups, pyxides (small boxes), chalices, and pithoi (very large handmade vases, sometimes over 1.7 m high and used for food storage).

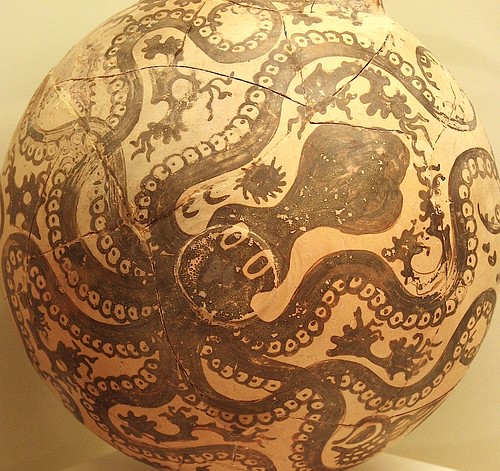

The New Palace period (c. 1600 BC to 1450 BCE) saw an evolution in technique and, with it, developments in both form and design, including the production of terracotta sarcophagi. More slender vases, tapering at the base became common, and new designs appeared such as the stirrup jar with one real opening and a second false one with two handles. Spirals and lines are now restricted to areas around handles and necks with, instead, plants and marine life taking centre stage. The Floral Style most commonly depicts slender branches with leaves and papyrus flowers. Perhaps the most celebrated example of this style is the jug from Phaistos which is entirely covered with grass decoration.

The contemporary Marine Style, meanwhile, is characterised by detailed, naturalistic depictions of octopuses, argonauts, starfish, triton shells, sponges, coral, rocks and seaweed. Further, the Minoans took full advantage of the fluidity of these sea creatures to fill and surround the curved surfaces of their pottery. Bull's heads, double axes, and sacral knots also frequently appeared on pottery, too.

The New Palace Style arrives from 1450 BCE. Perhaps influenced by increasing contact with the Mycenaean culture from the Greek mainland, typical examples are the three-handled amphorae, squat alabastron vessels, goblets and ritual vessels with figure-of-eight handles. Wares are decorated with much more schematic and stylised representations than the previous styles, with new designs not seen before including birds, warriors, and shields.

Minoan Stone Vessels

Besides terracotta, the Minoans also made vessels from a wide variety of stone types, laboriously carving the material out using chisels, hammers, saws, drills and blades. The vessels were finished by grinding with an abrasive such as sand or emery imported from Naxos in the Cyclades. Most designs were inspired by contemporary pottery shapes and even pottery decoration such as the Marine Style was transferred to stone vessels.

Popular shapes in stone include the 'bird's nest' lidded bowl which tapered significantly at the base and was probably used to store thick oils and ointments. As artists grew in confidence other, more ambitious and larger, vessels were made such as ritual vases or rhyta which could take many forms and which were usually covered in gold leaf. Perhaps the most famous example is the serpentine bull's head from the Little Palace at Knossos (c. 1600-1500 BCE) which is now in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. With gilded wooden horns, rock crystal eyes and a white tridacna shell muzzle the animal is superbly rendered, capturing a life-like pose that would not be equalled in art until Classical Greek sculpture a millennium later.

Minoan Sculpture

Figure sculpture is a rare find in the archaeology of Crete but enough small figurines survive to illustrate that Minoan artists were as capable of capturing movement and grace in three dimensions as they were in other art forms. Early figurines in clay are less accomplished but show the dress of the time with men (coloured red) wearing belted loin cloths and women (coloured white) in long flowing dresses and open-fronted jackets. There are also bronze figurines, typically of worshippers but also of animals, especially oxen.

Later works are more sophisticated and amongst the most significant is a figurine in ivory of a man leaping in the air (over a bull which is a separate figure). The hair would have been added using bronze wire and the clothes in gold leaf. Dating to 1600-1500 BCE, it is perhaps the earliest known attempt in sculpture to capture free movement in space. Another representative piece is the striking figure of a goddess brandishing a snake in each of her raised hands. Rendered in faience, the figurine dates to around 1600 BCE. Her bare breasts represent her role as a fertility goddess, and the snakes and cat on her head are symbols of her dominion over wild nature. Both figures are in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, Crete.

Minoan Frescoes

The Minoans decorated their palaces with true fresco painting (buon fresco), that is, the painting of colour pigments on wet lime plaster without a binding agent so that when the paint is absorbed by the plaster it is fixed and protected from fading. Fresco secco, which is the application of paint, in particular for details, onto a dry plaster was also used throughout the palaces as was the use of low relief in the plaster to give a shallow three-dimensional effect. Colours employed were black, red, white, yellow, blue, and green. There are no surviving examples of shading effects in Minoan frescoes, although, interestingly, sometimes the colour of the background changes whilst the foreground subjects remain unchanged. Although the Egyptians did not use true fresco, some of the colour conventions of their architectural painting were adopted by the Minoans. Male skin is usually red, female is white, and for metals: gold is yellow, silver is blue, and bronze is red.

Frescoes decorated the walls (either in their entirety or above windows and doors or below the dado), ceilings, wooden beams, and sometimes floors of the palace complexes. They depicted first abstract shapes and geometric designs, and then, later, all manner of subjects ranging in scale from miniature to larger-than-life size. Scenes of rituals, processions, festivals, ceremonies, and bull sports were most popular. Once again scenes from nature were common, especially of lilies, irises, crocuses, roses, and also plants such as ivy and reeds. Indeed, the Minoans were one of the earliest cultures to paint natural landscapes without any humans present in the scene; such was their admiration of nature. Animals, too, were often depicted in their natural habitat, for example, monkeys, birds, dolphins, and fish. Although Minoan frescoes were often framed with decorative borders of geometric designs the principal fresco itself, on occasion, went beyond conventional boundaries such as corners and covered several walls, surrounding the viewer.

Celebrated examples of Minoan frescoes include two young boxers, young men carrying rhytons in a procession, a group of male and female figures leaping over a bull, a large-scale seated griffin against a bold red background, and dolphins swimming above a sea floor of urchins. These can be seen at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, and in situ (reproductions) at Knossos, Crete.

Minoan Jewellery

Smelting technology in ancient Crete allowed for the refining of precious metals such as gold, silver, bronze, and gold-plated bronze. Semi-precious stones were used such as rock crystal, carnelian, garnet, lapis lazuli, obsidian, and red, green, and yellow jasper. Amethyst was also popular and was imported from Egypt where it was no longer fashionable in jewellery, a fact which illustrates the Minoan independence of mind regarding materials and design. Faience, enamel, steatite (soapstone), ivory, shell, glass-paste, and blue frit or Egyptian blue (a synthetic intermediate between faience and glass) were also at the disposal of Minoan jewellers.

Minoan jewellers possessed the full repertoire of metalworking techniques (except enamelling) which transformed precious raw material into a staggering array of objects and designs. The majority of pieces were constructed by hand, but such items as rings were often made using three-piece moulds and the lost-wax technique. Beads were sometimes made that way, too, allowing a certain mass production of these items.

Gold was the most prized material and was beaten, engraved, embossed, moulded, and punched, sometimes with stamps. Other techniques included dot repoussé, filigree (fine gold wire), inlaying, gold leaf covering and finally, granulation, where tiny spheres of gold were attached to the main piece using a mixture of glue and copper salt which, when heated, transformed into pure copper, soldering the two pieces together.

Jewellery took the form of diadems, necklaces, bracelets, beads, pendants, armlets, headbands, clothes ornaments, hair pins and hair ornaments, pectorals, chains, rings, and earrings. Rings deserve special mention as they were not only decorative but also used in an administrative capacity as seals. The majority consisted of a slightly convex oval gold bezel at a right angle to a plain hoop, also of gold. Ring bezels were most often engraved with detailed miniature scenes representing hunting, fighting, bull-leaping, goddesses, mythological creatures, and flora and fauna. These miniature masterpieces, like frescoes and pottery decoration, illustrate the Minoan fondness for filling the entire available surface even if figures had to be distorted in order to be accommodated. Another field of the Cretan jeweller and engraver was decorated weapons such as sword blades, hilts and pommels engraved with figures.

Two of the finest Minoan jewellery pieces are pendants, one of a pair of bees and the other showing a figure holding birds. The former was found at Malia and is in the form of two bees (possibly also wasps or hornets) rendered in great detail and realism, clutching between them a drop of honey which they are about to deposit into a circular, granulated honeycomb. Above the bees is a spherical filigree cage enclosing a solid sphere, and below the pendant hang three cut-out circular disks decorated with filigree and granulation. The second pendant, commonly known as the Master of the Animals pendant, is from Aegina, although research has shown it to be of Cretan origin and most probably looted in the Mycenaean period. The pendant consists of what appears to be a nature god or priest holding the neck of a water bird or goose in each hand and dressed in typical Minoan costume - belt, loincloth, and frontal sheath. Five disks hang from the base of the pendant.

Legacy

Minoan artists greatly influenced the art of other Mediterranean islands, notably Rhodes and the Cyclades, especially Thera. Minoan artists were themselves employed in Egypt and the Levant to beautify the palaces of rulers there. The Minoans also heavily influenced the art of the subsequent Mycenaean civilization based on mainland Greece. Mycenaean potters, jewellers, and fresco painters, in particular, copied Minoan techniques, forms, and designs, although they did make their marine life, for example, much more abstract, and their art, in general, included many more martial and hunting themes.

As for later times in Archaic and Classical Greece, the influence of Minoan and then Mycenaean art is difficult to trace with concrete examples. The later Greeks were certainly aware of the heritage of their forefathers in the Aegean; tholos tombs and the citadel of Mycenae were never buried from sight, for example. Depictions of double axes (or labrys) in stone and fresco may have combined to give birth to the legend of Theseus and the labyrinth-dwelling Minotaur so popular in classical Greek mythology. The lasting legacy of the Minoans, though, is best described here by the art historian R. Higgins:

Perhaps the greatest contribution of the Bronze Age to Classical Greece was something less tangible; but quite possibly inherited: an attitude of mind which could borrow the formal and hieratic arts of the East and transform them into something spontaneous and cheerful; a divine discontent which led the Greek ever to develop and improve his inheritance. (Higgins, 190)