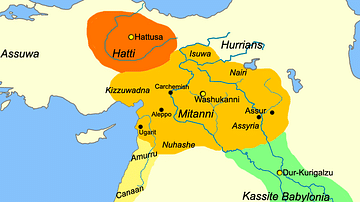

The Kingdom of Mitanni, known to the people of the land, and the Assyrians, as Hanigalbat and to the Egyptians as Naharin and Metani, once stretched from present-day northern Iraq, down through Syria and into Turkey and was among the greatest nations of its time, though today it is largely forgotten.

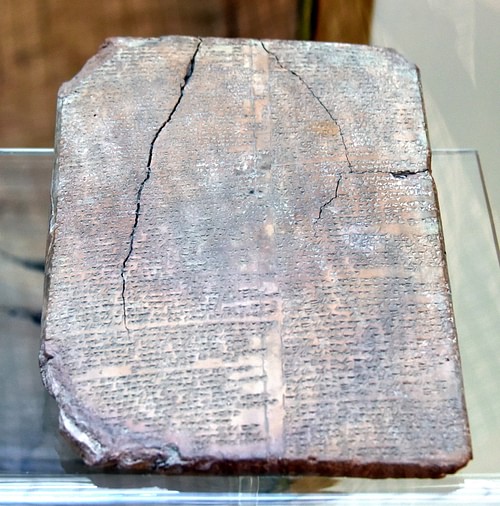

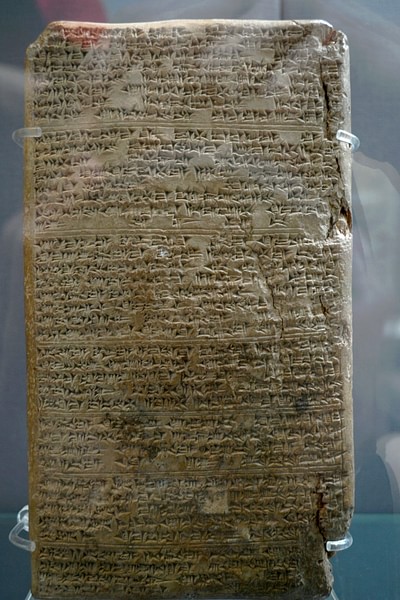

Few records of the people themselves exist, but correspondence between kings of Mitanni and those of Assyria and Egypt (the Amarna Letters) as well as the world's oldest horse-training manual, and a treaty between the Mitanni and Hittites, give evidence of a prosperous nation which thrived between 1500 and 1240 BCE. In the year 1350 BCE, Mitanni was powerful enough to be included in the Great Powers Club along with Egypt, the Kingdom of the Hatti, Babylonia, and Assyria.

Beginning in the 14th century BCE, however, Assyrian incursions weakened the Mitanni kingdom as the Assyrian king Ashur-Uballit I (r. 1365-1330 BCE) annexed significant territories. Disputes of succession among Mitanni royalty added to the kingdom's difficulties, and this lack of unity made Mitanni easy prey for the Hittites under their king Suppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344-1322 BCE) who deported large segments of the population and replaced them with Hittites.

The Assyrian king Adad Nirari I (r. c. 1307-1275 BCE) took the region and, again, deported segments of the population, replacing them with Assyrian subjects. His son and successor, Shalmaneser I, completed the conquest of Mitanni c. 1250 BCE, and his son, Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. c. 1244-1208 BCE), defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Nihriya c. 1245 BCE, eliminating them as a power in the region and obliterating the now greatly reduced Kingdom of Mitanni, which then became part of the Assyrian Empire.

People of Mitanni & Name

The Mitanni kingdom ruled over the northern Euphrates-Tigris region between c. 1475 BCE and c. 1275 BCE. The early people of the region have been variously identified as migratory Indo-Iranians or Indo-Aryans, and they have even been associated with the Semitic Hyksos, but their ethnicity continues to be debated. Scholars have attempted to identify them with one or another group based on the deities' names invoked in a treaty with the Hittites, but both Indo-Aryans and Indo-Iranians (once part of the same migratory band from Central Asia) venerated gods such as Indra, Mithra, and Varuna, among others.

It is thought the ruling class were warriors known as Maryannu, which gave the kingdom its name Mitanni when it was translated by the Egyptians as "Naharin" and "Metani". The Assyrians knew the kingdom as Hanigalbat (also given as Khanigalbat, Hani-Rabbat), and the Hittites referred to the people as the Huri and their territory as the land of the Huri (or Hurri) and land of the Hurrians, and so most modern-day scholars agree they were Hurrians. They used the language of the local people, which was at that time a non-Indo-Iranian language, Hurrian. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick writes:

The population of Mitanni was predominantly Hurrian, but the ruling elites were Indo-European warriors who called themselves Mariannu and who worshipped deities with Vedic names such as Indar, Uruwana, and the collective Devas. This elite was to intermarry with the local population, as the names of their children testify. (120)

The capital of Mitanni was Washukanni, located on the headwaters of the River Habur, a tributary of the Euphrates. The name "Washukanni" is similar to the Kurdish word bashkani, bash meaning "good" and kanî meaning "well" or "source", and so is translated as "source of good" but also as "source of wealth". Some scholars have claimed that the ancient city of Sikan was built on the site of Washukanni and that its ruins may be located under the mound of Tell el Fakhariya near Gozan in Syria.

Since there are few written records from the people themselves, however, any discussion of the Kingdom of Mitanni eventually involves considerable speculation. What the kings of the people did and what other nations they interacted with is known, but nothing of the people's daily lives and religious beliefs. It is clear, however, they were a considerable power in the Near East beginning c. 1500 BCE.

The Great Kingdom

At its height, the Mitanni kingdom controlled trade routes down the Habur to Mari and up the Euphrates to Carchemish. They also controlled the upper Tigris and its headwaters at Nineveh. Their allies included Kizuwatna in southeastern Anatolia, Mukish, which stretched between Ugarit and Qatna west of the Orontes to the sea, and the Niya which controlled the east bank of the Orontes from Alalakh down through Aleppo, Ebla, and Hama to Qatna and Kadesh in modern-day Syria.

To the east, the Mitanni had good relations with the Hurrian-speaking Kassites whose territory corresponds to present-day Kurdistan. The lands of the Mitanni in northern Syria bordered eastern Anatolia to its west and extended east as far as Nuzi (present-day Kirkuk, Iraq) and the river Tigris in the east. In the south, it extended from Aleppo across to Mari on the Euphrates to the east. The entire region was fertile and allowed for agriculture without artificial irrigation. Herds of cattle, sheep, horses, and goats were raised, and the Mitanni were famed horsemen and charioteers.

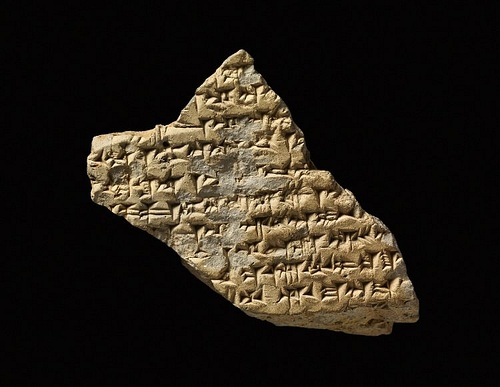

It is recorded that they were the innovators who spearheaded the development of the light war chariot with wheels that used spokes rather than solid wood wheels, such as those used by the Sumerians, so that the chariots were faster and easier to maneuver. Excavations of the Hittite archives of Hattusa, near present-day Boğazkale (Turkey), found the oldest surviving horse-training manual in the world. The work was written in 1345 BCE on four tablets and contains 1080 lines by a Mitanni horse-trainer named Kikkuli, beginning with the words, "Thus speaks Kikkuli, master horse trainer of the land of Mitanni" and exhaustively describes the proper methods of training horses.

Kings of Mitanni

Little is known of the early kings of Mitanni owing to the later destruction of the culture by the Assyrians, but the names of the early rulers are known through the correspondences with other countries. In the 16th century BCE, the most prominent kings seem to have been Kirta, his son Shuttarna I, and Barratarna (also given as Parshatatar). King Shaushtatar (r. c. 1430 BCE) extended the boundaries of Mitanni through the conquest of Alalakh, Nuzi, Assur, and Kizzuwatna. Egypt, under Thutmose III (r. 1479-1425 BCE), defeated the Mitanni at Aleppo after a long period of contention over control of the region of Syria.

The Mitanni king Artatama I reigned during the time of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE) and Thutmose IV (1400-1390 BCE), but little is known of him other than attempts at forming treaties with Egypt through marriages. His son, Shuttarna II, arranged the marriage of his daughter, Kilu-Hepa, with Amenhotep III (r. 1391-1353 BCE), strengthening relations and helping Mitanni to consolidate power and secure its borders.

Under Shuttarna II, Mitanni attained its height of power and prestige and was listed among the so-called Great Powers Club (also given as Club of the Great Powers). This is a modern-day designation for the strongest nations of the region including Egypt, Babylonia, and the Kingdom of the Hatti (Hittites) of Anatolia who interacted with each other through trade and alliances.

Treaties and trade agreements have survived from this era and later periods, but nothing more substantial to give a clear picture of how Mitanni operated as a political and cultural force in the region. Other civilizations are well-documented, but how, and often when, Mitanni interacted with them is far from clear. Scholar Marc van de Mieroop comments:

The greatest difficulty confronting us is the uncertainty about chronology. While we may feel cautiously confident about the sequence of rulers and lengths of reigns in certain states, information about other kings and kingships remains very vague. Thus, even writing the history of the Mitanni state, for example, poses great difficulties, as we cannot date events based on evidence from the state itself. We have to rely on synchronisms with Egypt and Hatti to find out approximately when and how long a Mitanni king ruled. (130)

One of the best-documented periods of the Mitanni kings is that of the reign of Shuttarna II and his son Tushratta, only because of the correspondence known as the Amarna Letters, and even this is hardly complete.

King Tushratta & the Coming of the Hittites

The daughter of King Tushratta, the princess Taduhepa (also given as Tadukhipa), was arranged in marriage to Amenhotep III as part of a treaty that further balanced power between the two nations. Some scholars have identified Taduhepa with the famous Egyptian queen Nefertiti (l. c 1370 to c. 1336 BCE), wife of Amenhotep III's son, Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) or with Akhenaten's lesser wife Kiya, but these claims are generally dismissed by scholars.

Tushratta sent a large dowry with his daughter which included the statue of the patron deity of Washukanni, the goddess of fertility Sauska. Amenhotep III was ill at this time, and Sauska, who also presided over healing, was sent to alleviate whatever ailed him but also, as a love goddess, to bless the marriage and strengthen the union. A list of the gifts is included in correspondence between the two kings and included gold, lavishly ornamented horse saddles and camel litters, jewelry, and expensive clothing.

This treaty was put to the test twice. First, when Tushratta wrote Amenhotep III afterwards that he had not received as much gold from Egypt as part of the marriage transaction as expected and then when Tushratta's authority was challenged by a coup in his home city. The treaty would not survive this second test which involved a power struggle in Washukanni between Tushratta and a relative (possibly his brother), known as Artatama II. Egypt backed Tushratta in this conflict while the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344-1322 BCE) backed Artatama II. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

The Hittites vied with the kingdom [of] Mittani which had sealed off the Mesopotamian north all the way from near the sea in the west to the mountains in the east, from the area of Aleppo to the region of Kirkuk. (219)

The Hittites, hoping to break the Mitanni hold on trade routes, seem to have brokered a deal with Artatama II to stage a coup, but it appears that Tushratta had the support of his nobles and clearly did have the strength of Egypt behind him at first. Tushratta seemed poised to succeed when Egypt, fearing the growing power of the Hittites, withdrew its support. Suppiluliuma I, tired of diplomacy and now free to do as he pleased without fear of Egyptian reprisal, led his forces on Washukanni and sacked it. Tushratta was assassinated by his son, perhaps in an effort to save the city. Following this conquest, Mitanni was ruled for a time by the Hittites through puppet kings who advanced their agenda.

The Assyrian Conquest of Mitanni

Suppiluliuma I divided the former kingdom into two provinces with their capitals at Aleppo and Carchemish. The remainder of the region kept some degree of autonomy, though still a vassal state, and was referenced by the Hittites as "Hanigalbat". At some point, the region fell under the yoke of the Assyrian Empire. Exactly when is not clear, but possibly during the reign of the Hittite king Mursili II, (r. 1321-1295 BCE) and definitely before the reign of Tudhaliya IV and the Battle of Nihriya in 1245 BCE, which marks the beginning of the decline of the Hittite Empire.

The Assyrian king Adad Nirari I left inscriptions telling of how an upstart Hittite king Shattuara I challenged his might and so Adad Nirari I marched on Mitanni, crushed their forces in battle, and carried Shattuara I back to Ashur in chains where he was forced to swear an oath of allegiance to the Assyrian ruler. While still an autonomous state, the kingdom now owed tribute and allegiance to Assyria and was no longer considered an equal of the other powers of the region.

Mitanni was further reduced during the reign of Adad Nirari's son, Shalmaneser I (r. 1270s to 1240s BCE), when King Shattuara II of Mitanni rebelled against Assyria with the aid of a nomadic tribe known as the Ahlamu around 1250 BCE. Shattuara's forces were well organized, fully armed, and had occupied all the mountain passes and waterholes to effectively cut off the Assyrian army's water supply and severely hamper their attempts at foraging.

Even so, hungry and thirsty, Shalmaneser's army won a crushing victory. He claims in the records to have slain 14,400 men and the survivors were blinded and carried away. His inscriptions mention the conquest of nine fortified temples, 180 Hurrian cities were "turned into rubble mounds" and Shalmaneser "…slaughtered like sheep the armies of the Hittites and the Ahlamu his allies…".

The cities from Taidu (also known as Taite) to Irridu were captured (an area which today comprises northern Iraq through Syria), as well as all of the region of the Mount Kashiyari range down to and including the city of Eluhat (also known as Eluhut which was located south-east in modern-day Turkey). A large part of the population of the conquered regions was sold into slavery and deported. Shalmaneser's son, Tukulti-Ninurta I, defeated the Hittites at Nihriya in 1245, ending their control of the region and absorbing Mitanni fully into the Assyrian Empire.

Conclusion

Afterwards, Mitanni was forgotten as a political entity until archaeological excavation of the region in the modern day and the discovery of the Amarna Letters in 1887. These letters, found at the site of el-Amarna in Egypt, are the correspondence between Egyptian monarchs and others of the Great Powers Club which, as noted, included Mitanni.

The Kingdom of Mitanni continues to pose problems for historians and archaeologists, however, owing to its complete destruction by the Assyrians. Even today, most scholars are able to provide only the briefest outline of the history of the kingdom and its culture based on the meager surviving documents and artifacts such as cylinder seals identified with the Mitanni. Scholar H. J. Kantor, for example, writes:

Among the states of the Second Millennium BCE, the kingdom of Mitanni was one of the most artificial and short-lived. For a few centuries, certain areas of northern Syria, centering around the Harbur Valley, which neither before or after enjoyed an independent political union, were wielded into a single unit by a small ruling group, a dynasty of kings with Indo-European names, supported by a knightly class. Although the independence of Mitanni was only maintained by adroit manipulation of the unstable balance of power that was characteristic of the Near Eastern world in the latter part of the Second Millennium, this state was yet sometimes powerful enough to extend its influence and hegemony beyond its own frontiers. (1)

Although Kantor goes on to discuss artifacts associated with Mitanni, her description of the state itself, as with other scholars, provides little more than a glimpse of what Mitanni may have been. Even though more is claimed to be known of Mitanni today than in the past, scholars are still working with, essentially, the same basic information they had in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until further artifacts or documentation are brought to light by archaeologists, this situation will remain unchanged, and persistent military conflict in the region continues to prevent efforts that could provide a clearer picture of the great kingdom that was Mitanni.