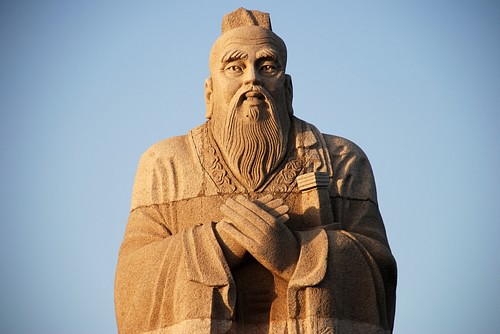

Mo Ti (l. 470-391 BCE, also known as Mot Tzu, Mozi, and Micius) was a Chinese philosopher of the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) associated with the Hundred Schools of Thought (different philosophical schools which established themselves in this era). He is the founder of Mohism (also given as Moism), a philosophical system advancing the concept of consequentialism (one's actions define one's character) and emphasizing universal love as the meaning of life and the solution to all conflict.

Little is known of his life other than he was a carpenter and inventor of various devices (specifics unknown) and came from the state of Lu (modern-day Shandong province), the same region as the philosopher Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE), whose precepts Mo Ti strongly disagreed with just as he rejected the vision of Lao Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE), the legendary (and possibly mythical) founder of Taoism.

Mo Ti's skill in carpentry made him a valuable asset to the warring states in constructing quality siege ladders and fortifications. In an effort to level any state's advantage over another, he provided each with exactly the same benefit, not only in material products but strategy and intelligence. He hoped, by this stratagem, to neutralize their efforts and bring them to an understanding of the value of peace and futility of war, but his labors were in vain. Even though he was able to clearly make his point to some kings, none of them adopted his philosophy. He seems to have continued, in spite of the apparent futility of his mission, until he realized that none of the states were going to choose universal love over the pursuit of personal power.

His dedication to the cause of peace was recognized and admired even by his harshest critic, the Confucian philosopher Mencius (l. 372 -289 BCE), and his philosophy did attract adherents, just not those he was hoping to convert. When the state of Qin finally defeated the others and founded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), Mo Ti's works (along with those of Confucius and Lao Tzu) were banned and the philosophy of Legalism embraced. During the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE), Confucianism was adopted as the national philosophy, and Mohism was forgotten until its revival in the 20th century CE.

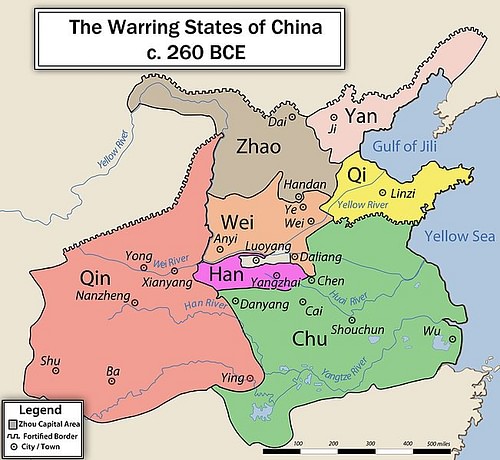

The Warring States & Mo Ti

The Warring States Period in China (c. 481-221 BCE) was the era in which seven independent states fought each other for supreme control of the government. The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was still recognized as the ruling house from Luoyang but in name only; they no longer had the power to enforce any of their laws nor perform any functions associated with a strong and stable state.

The Zhou Dynasty established itself as a decentralized government with separate states, nearly autonomous, loyal to the Zhou king who had granted the lands. In time, these states grew more powerful than the king and, as royal authority diminished, each state began to contend with the others for supremacy. None could gain the advantage, however, because each used the same tactics and observed the same laws of chivalry in warfare.

Mo Ti was a highly skilled carpenter and craftsman who became an expert in building siege ladders and designing fortifications and so was in high demand among the rulers of the seven states in helping them defeat each other. Although initially it appears that Mo Ti did design and build various devices and fortifications for the warring parties, he recognized that war was senseless and antithetical to the goodness of life and began trying to maintain each states' ability for attack or defense at the same level in order to maintain balance between them.

As noted, the states were already frustrated in trying to gain an advantage over each other and this led to their seeking Mo Ti's help in providing them with an edge; instead, he further leveled the playing field to impress upon them the futility of the ongoing wars. He understood that the states were only fighting each other out of self-interest, not because they wanted to do any good for the people, and believed this kind of behavior was simply selfish and fundamentally immoral. The historian Will Durant comments:

[Mo Ti believed] selfishness is the source of all evil, from the acquisitiveness of the child to the conquest of an empire [and] marvels that a man who steals a pig is universally condemned and generally punished while a man who invades and appropriates a kingdom is a hero to his people and a model to posterity. (678)

Mo Ti devoted himself to travel between the warring states in an effort to convince the rulers to embrace love and pacifism. One of the best-known examples of his strategy is when he traveled to the state of Chu in order to stop their ruler, Gonshu Ban, from attacking the state of Sung. Mo Ti ably defeated Gonshu Ban in a series of war games and then informed Gonshu that he had already provided Sung with help in fortifications and strategy and so an attack would be futile. Gonshu Ban then called off his attack.

Mohism

Even though, through episodes like this, Mo Ti seemed to make an impression on a ruler and was able to save lives, his successes appear to have been few. Still, although his efforts were largely unsuccessful and he was often mocked, this did not in any way dissuade him from his course. He had earlier set up a school in his native state of Lu, in which he trained students in carpentry and Chinese philosophy, and many of these students became ardent disciples and helped him spread his message of universal love.

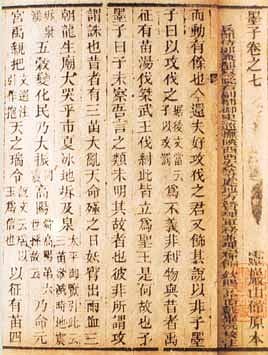

Mo Ti believed that love began close at hand with one's family and friends but should by no means end there. He preached an “impartial love” whereby one would regard all people as members of one's family. This teaching was at odds with the already-popular Confucian concept of respect for one's family and one's ancestors above all others, but Mo Ti countered the criticism by pointing out that, in his philosophy, one still had to honor one's family and kin but then treat others in the same way.

This belief formed the basis of Mo Ti's ethics of consequentialism in which one's individual behavior, regardless of proscribed ritual, dictates one's character and, by extension, the quality of the state. If one is kind and lives a harmonious existence, one will draw kindness and harmony to oneself and, conversely, if one is contentious and spiteful, one will attract a like response from others. Simplicity in all things, and adherence to the principle of universal love, was at the heart of Mohism. Mo Ti writes:

Men in general loving one another, the strong would not make prey of the weak, the many would not plunder the few, the rich would not insult the poor, the noble would not be insolent to the mean, and the deceitful would not impose upon the simple. (Durant, 678).

Through love, and sharing all things, he claimed, China would find peace and could leave behind the constant warfare which marked the world he knew.

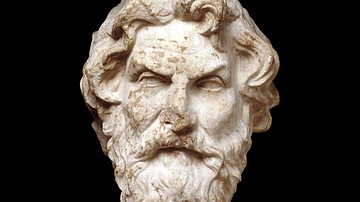

His philosophy gained a groundswell of support but was criticized as being too idealistic and impractical. The philosopher Mencius, the great proponent and codifier of Confucianism, condemned Mo Ti's concept of universal love as subversive and called for its suppression. He considered Mohism as dangerous a belief system as the hedonism of the egoist philosopher Yang Zhu (l. 440-360 BCE) claiming that they undermined the authority of traditional understanding and practice and were intent on turning rational people into wild beasts. Scholar Arthur Waley comments:

[Mencius] speaks of Mo Tzu, who taught that all men should love one another no less than they loved themselves as 'abolishing fatherhood', merely because fathers lose in Mo Tzu's system the unique position they hold in Confucianism. And because Yang Tzu held that each individual should perfect himself spiritually and physically, rather than sacrifice himself to the supposed good of the community, Mencius says that the followers of Yang Tzu 'abolish prince hood', that is to say, do away with all governmental authority, and that Yang Tzu and Mo Tzu both wish to reduce mankind to the level of wild beasts. (120-121)

Mo Ti was actually arguing the contrary of Mencius' claim: by embracing universal love for all people, regardless of their social class or relationship to one's self, one was actually upholding the fundamental principles of true government, the care for and protection of the people, as well as the spirit of Confucianism in improving one's moral character and conduct. Even so, Mo Ti's vision did contradict Confucian insistence on the importance of ritual and proper behavior in establishing good character and also refuted the Taoist claim that one need only align one's self with the cosmic Tao to find inner peace.

Conflict with Confucianism & Taoism

The Confucian concept of character, at first glance, seems in line with Mo Ti's consequentialism –behavior defines the individual – but the significant difference is that Mo Ti claims that one's behavior is a reflection of personal spiritual work while Confucius maintains it is the result of following precise rituals in a specific manner.

Confucius believed that proper behavior encouraged good character; if one behaved well, in accordance with accepted custom, one would become a good person. Mo Ti maintained that observing ritual and custom could not make a person good; one had to devote one's self to personal, spiritual work, subjugating self-interest for the good of others, in order to be considered a good person.

Mo Ti also disagreed with the Taoist vision of a cosmic force, the Tao, which informs and binds all things together. Mo Ti's philosophy would also seem to align with aspects of Taoism in the belief that there is a natural “flow” to human existence which, once one understands and recognizes it, encourages a more peaceful and harmonious relationship with the world, one's self, and other people but, in Taoism, this is the Tao; in Mohism, it is universal love. One could see the effects of embracing universal love in a person's behavior, Mo Ti noted, while one could not in claiming one was living in accord with an invisible force. Scholar John M. Koller comments:

[Mo Ti] argued that the way to improve the human condition was to tend to the immediate welfare of the people. The slogan of the Moists was “promote general welfare and remove evil.” The criterion advocated for measuring how good anything is was its usefulness in achieving human happiness. Ultimately, according to Moism, value was to be measured in terms of benefits to the people. Benefits, in turn, could be measured in terms of increased wealth, population, and contentment. (205)

Mo Ti maintained that only through reflection, self-study, and sincere behavior which was true to one's self and the concept of universal love could one become good, not through adherence to ritual and conformity and not through connection with some invisible “force” which flowed through all of existence. He argued that what was good for humanity was easily apprehended through empirical observation. One could recognize “good” through its effects on people just as one could understand what was “bad” through negative reactions and suffering.

Mo Ti & Ghosts

Mo Ti's philosophy was, of course, rejected by the Confucians and Taoists and its acceptance was not helped by his well-known belief in the existence of ghosts who walked among and could interact with the living on a daily basis (which ran counter to the accepted understanding of the dead as existing in another realm or appearing only when troubled) even though he argued his beliefs on rational grounds. He reasoned that, when people tell of how a certain machine operates with which one is not acquainted, or of how certain people behave or speak in a land one has never been to, one should accept what is said if their report seems credible and if they, themselves, have proven reliable in the past. Following this line of reasoning, one should accept what is said about ghosts if those who tell about them can be trusted in what they have said about other subjects.

As ancient historical accounts, as well as contemporary reports, contained references to ghosts interacting with the living, they should be accepted as a reality in the same way one recognized established history and news reports of the day, even if one has not experienced a ghost oneself. Further, he claimed, even if ghosts do not exist as reported, the communal rituals involved in honoring, appeasing, or protecting one's self from them would provide occasions to “gather our relatives and neighbors and participate in the enjoyment of the sacrificial victuals and drinks” (Durant, 678). These gatherings would offer the opportunity for people to express love for one another as well as the departed and would bind the community more closely.

Still, his arguments were not met with success since a belief in ghosts walking, talking, and otherwise interacting with the living contradicted the long-held belief in ancestor worship in which the dead enjoyed an existence removed from the world of mortality and strife. Reports of apparitions were never received well in ancient China as they were interpreted to mean the dead were troubled the natural order upset.

Conclusion

The Warring States Period was concluded with the victory of the state of Qin over the other six states and the ascent of the first emperor of China, Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE). Following Shi Huangdi's rise to power, the Chinese emperor ordered the burning of all books which did not support his philosophy of Legalism or his dynasty's version of history.

The works of Confucius, Mo Ti, and many others were burned but Confucian concepts survived through the devotion of his adherents and the widespread acceptance of his precepts which were revived during the Han Dynasty. Taoism, also, survived because its precepts had long been ingrained in the culture through its close association with folklore and legend.

Mo Ti's philosophy, however, which had never gained as widespread acceptance as either of these, was largely forgotten, as was his name, by the time the Han emperor Wu the Great (r. 141-87 BCE) made Confucianism the national philosophy of China. Mo Ti's work was more or less ignored until the Communist Party of China revived interest in it in the mid-20th century CE, recognizing in it a kind of proto-communist vision. Today he is recognized as one of China's greatest philosophers, and his concept of consequentialism is regarded as on par with any other philosophical system.