The Moabite Stone, otherwise known as the Mesha Stele, contains an ancient inscription by Mesha, King of Moab during the late 9th century BCE, elements of which match events in the Hebrew Bible. The inscription describes two aspects of how Mesha lead Moab into victory against ancient Israel. First, he claims to have defeated ancient Israel on many fronts, capturing or reclaiming many cities and slaying the inhabitants. Second, Mesha claims to have reconstructed or repaired many cities and buildings, including a fortress, king's residence, and cisterns for water storage. Unfortunately, the last five lines of the inscription are broken. So, scholars are unsure exactly how the Moabite Stone ends.

In what follows, we will first consider how the Moabite stone was discovered. Subsequently, a brief summary of the Moabite stone, along with a full translation, will be presented. To understand the purpose of the text, we will briefly consider the function of the Moabite Stone. Having identified the function of the Moabite Stone in history, we will consider how it sheds light on the broader history of the region. Finally, two pressing issues will be discussed: the Moabite deity Chemosh and the representation of religion and politics in the Moabite Stone.

Discovery

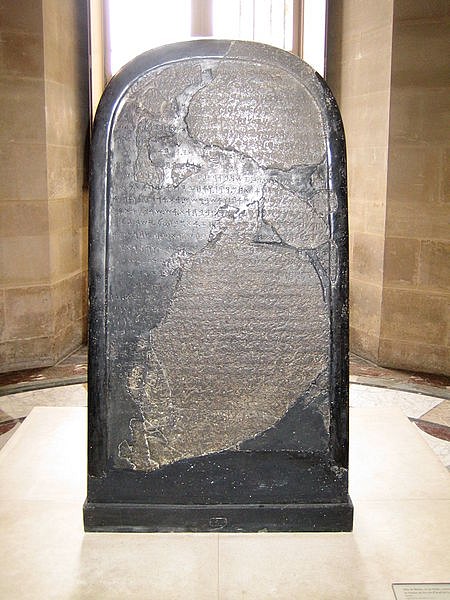

The Moabite Stone was discovered 1868 CE at Dhibān, amidst a time in which scholars sought for any inscriptions and other proofs for the historicity of the Bible. So, when the scholar Charles Clemont-Ganneau heard that the missionary F.A. Klein had discovered a large stone with writing in Dhibān, he sent two people for further information. The first person made a copy of the text. For unknown reasons, his second intermediary aroused the anger of villagers. This resulted in the shattering of the Moabite stone. After purchasing and locating the various fragments on the antiquities market, Clermont-Ganneau was able to reconstruct the entire stone.

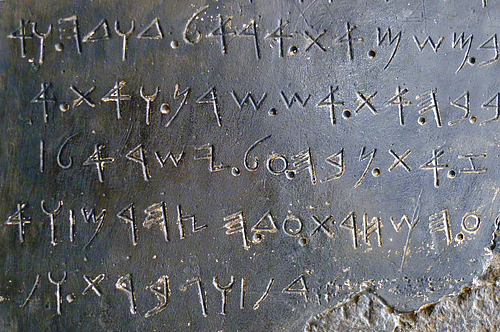

Its measurements are 1.15 metres high and 60-68 centimeters wide. 33 lines of writing are legible on the stone. The written language is most likely Moabite. Currently, the original Moabite Stone is housed at the Louvre Museum in Paris. A copy is on display at the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

Summary of the Moabite Stone

The Moabite Stone is written in the 1st person, the speaker being Mesha, King of Moab. Mesha ruled from about 850 BCE until the late 9th century BCE. Moab was located east of ancient Israel and Judah across the Dead Sea. To the south of Moab was Edom and to the north of Moab was Ammon.

The inscription opens by describing who Mesha is. In addition, the purpose of the stone itself is expressed: “because he (Chemosh, the Moabite deity; also written as Kemoš) delivered me from all assaults and because he let me see my desire upon all my adversaries” (modified from Gibson 1971). The adversary is specified as Israel, for King Omri of Israel had captured portions of Moab. Around the time when the son of Omri was king (c. 850 BCE), Mesha began to re-capture lost territory, rebuilding, slaying inhabitants, and taking Israelite slaves (lines 7-21). The next section of text describes various things which Mesha claims to have accomplished for the greater good: rebuilding towns, building cisterns for water, mending roads, and providing land for shepherds (lines 22-31). Unfortunately, the final five lines of the text are unclear and broken. Though conjectural, it is most likely that these lines further detail alliances established by Mesha or other campaigns completed by Mesha.

The Text of the Moabite Stone

[1] I am Mesha, the son of Kemoš-yatti, the king of Moab, from Dibon. My father was king over Moab for thirty years, and I was king after my father.

[2] And in Karchoh I made this high place for Kemoš [...] because he has delivered me from all kings, and because he has made me look down on all my enemies.

[3] Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemoš was angry with his land. And his son succeeded him, and he said - he too - "I will oppress Moab!" In my days he did so, but I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin, yes, it has gone to ruin for ever!

[4] Omri had taken possession of the whole land of Medeba and he lived there in his days and half the days of his son, forty years, but Kemoš restored it in my days. And I built Ba'al Meon, and I made in it a water reservoir, and I built Kiriathaim.

[6] And the men of Gad lived in the land of Ataroth from ancient times, and the king of Israel built Ataroth for himself, and I fought against the city, and I captured, and I killed all the people from the city as a sacrifice for Kemoš and for Moab, and I brought back the fire-hearth of [Daudoh] from there, and I hauled it before the face of Kemoš in Kerioth, and I made the men of Sharon live there, as well as the men of Maharith.

[7] And Kemoš said to me: "Go, take Nebo from Israel!" And I went in the night, and I fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, and I took it, and I killed its whole population, seven thousand male citizens and aliens, female citizens and aliens, and servant girls; for I had put it to the ban of Aštar Kemoš. And from there, I took the vessels of YHWH, and I hauled them before the face of Kemoš.

[8] And the king of Israel had built Jahaz, and he stayed there during his campaigns against me, and Kemoš drove him away before my face, and I took two hundred men from Moab, all its division, and I led it up to Jahaz. And I have taken it in order to add it to Dibon.

[9] I have built Karchoh, the wall of the woods and the wall of the citadel, and I have built its gates, and I have built its towers, and I have built the house of the king, and I have made the double reservoir for the spring, in the innermost of the city. Now, there was no cistern in the innermost of the city, in Karchoh, and I said to all the people: "Make, each one of you, a cistern in his house." And I cut out the moat for Karchoh by means of prisoners from Israel.

[10] I have built Aroer, and I made the military road in the Arnon. I have built Beth Bamoth, for it had been destroyed. I have built Bezer, for it lay in ruins.

[11] And the men of Dibon stood in battle-order, for all Dibon, they were in subjection. And I am the king over hundreds in the towns which I have added to the land.

[12] And I have built the House of Medeba and the House of Diblathaim, and the House of Ba'al Meon, and I brought there [...] the flocks of the land.

[13] And Horonaim, there lived [...]. And Kemoš said to me: "Go down, fight against Horonaim!" I went down [...] and Kemoš restored it in my days. And [...] from there [...]

[14] And I [...]

(from “The Stela of Mesha,” at Livius.org)

Historical Function of the Moabite Stone as Divine Justification

In the Moabite Stone, Mesha employs the same imperial strategies as other ancient Near Eastern kings: “A king must convince his god(s) and his subjects that his military acts have just causes in order to gain both divine and public support” (Na'aman 1997). In the Moabite Stone, Mesha accomplishes this by noting that Israel had suppressed Moab. Moreover, he mentions two times that Chemosh, the primary Moabite deity, commanded him to go and take the cities of Nebo and Horonaim. In doing so, Mesha provided divine justification for the wars that he waged against Israel. Similar rhetoric is present in texts like the Tel Dan inscription by an Aramaic King and 1 Samuel 23:2, both of which illustrate how kings needed to justify their military campaigns before their respective deities and subjects. That is to say, the Moabite Stone and its inscription are essentially a form of propaganda by Mesha, intended to justify his actions to both deities and people. Unfortunately, poorly planned archaeological digs at Dhibān, along with the problematic recovery of the Moabite Stone, make it difficult to identify how the Moabite Stone functioned in the broader, archaeological context.

History

Certain aspects of the Moabite Stone inscription agree with the only one other contemporary historical source, namely 2 Kings 3. According to 2 Kings 3:4, Mesha was subjugated under Ahab. Then, “when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel” (2 Kings 3:5). Subsequently, Joram, son of Ahab, attacked Moab: “When the Moabites came to Israel's camp, the Israelites rose up and struck down the Moabites. The Moabites fled from before them. They went forth into the land, slaughtering the Moabites” (2 Kings 3:24). In other words, the Moabites were suppressed by ancient Israel during the reigns of Omri (c. 885-874 BCE), Ahab (874-853 BCE), and Joram (854-841 BCE).

The Moabite Stone includes the similar timeline: “Omri, king of Israel, had oppressed Moab many days, for Chemosh was angry with his land. His son succeeded him, and he too said, I will oppress Moab” (Gibson 1971). Though the son is not mentioned by name, he is most likely the offspring of Omri, namely Joram. This is a point of contact consistent between the Moabite Stone and 2 Kings 3. At the same time, the Moabite Stone fails to mention how Omri, Ahab, and Joram went on campaigns against the Moabites. Likewise, 2 Kings does not detail how Mesha seized Israelite territory.

Moreover, 2 Kings 13:20 comments further on the Moabites: “Elisha died and they buried him. And a group of Moabites regularly invaded the land in the spring of that year.” If Elisha died around the beginning of the 8th century BCE, it suggests that Mesha successfully annexed certain regions of Israel during his reign, sometime between 840 BCE and 800 BCE; however, Moabite incursions into Israelite territory after the reign of Mesha were smaller in nature (i.e. groups of Moabites as opposed to the Moabite political entity).

The incursions of Moabites as small groups rather than a single, unified political entity by the end of the 9th century BCE can be corroborated with archaeological evidence, which suggests that Dhibān “shows little evidence from excavations of being a royal establishment” during the 9th century BCE (Dever 2016). In other words, Mesha appears to have attempted to make Moab a stronger political entity during his reign. Although Moabite leaders are mentioned in Neo-Assyrian documents in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE after the reign of Mesha, the strong, independent, political entity imaged in the Moabite stele failed to materialize nonetheless. Importantly, though, this interpretation is subject to change, as the studies on ancient Moabite archaeology are problematic and few in number.

For this reason, it is necessary to critically approach the Moabite Stone, or 2 Kings as a matter of fact, as it concerns history. Instead, the Moabite Stone needs to be corroborated with other historical texts, inscriptions, and archaeological data in order to identify the degree to which the Moabite stone reflects broader regional conflicts and the degree to which the Moabite stone reflects personal biases.

The Moabite Deity: Chemosh

As a chthonic (underworld) deity, Chemosh shows up in texts as early as the late 3rd millennium BCE in Ebla, Syria. He later appears in Ugarit texts around the 13th century BCE. He also appears as a chthonic deity in Neo-Assyrian texts (c. 8th century BCE). In the text of the Moabite Stone, he is mentioned ten times as the primary Moabite deity. So, though Chemosh is particularly significant to Moab in the 9th century BCE, he functioned in many cultures throughout the Levant prior to Moab.

Beyond the Moabite Stone, scholars know that Chemosh was important to Moabites on the basis of other archaeological sites and Moabite royal names in Neo-Assyrian texts. Another Moabite inscription, for example, is a brief dedicatory inscription, wherein Mesha claims to have built and dedicated a temple to Chemosh. Building temples to deities as a means of showing commitment to the deity and securing divine favor was common throughout the ancient Near East.

Religion & Politics in the Moabite Stone

Throughout the ancient Near East, religion and politics were inseparable. It is also so with the Moabite Stone. First, the primary deity of Moab, namely Chemosh, is said to have been the cause for Moab's oppression and Israel's success in war and politics: “Omri, king of Israel, had oppressed Moab many days, for Chemosh was angry with his land” (Gibson 1971). Mesha, then, claims to have become the remedy and means for re-capturing the land at the will of Chemosh. Similar sentiments are expressed throughout the Hebrew Bible, Assyrian inscriptions, and Babylonian inscriptions.

Second, one of the ways that Mesha established his political rule over ancient Israel was through employing symbolic, religious actions. So, after defeating the Israelite town of Ataroth, he claimed to have “brought back from there the cult stand of the god Daudoh, and dragged it before Chemosh at Kerioth” (modified from Gibson 1971; drawing from Na'aman 1997). Na'aman suggests that the cult stand of the god Daudoh was an object originally belonging to Moab, an object which a king of Israel had previously captured (Na'aman 1997). As such, it demonstrates how returning religious materials to their proper place was a way of demonstrating political might.

Third, Mesha demonstrated his success in the region by subordinating deities and religious materials foreign to Moab before Chemosh: “I took from thence the vessels of Yahweh and dragged them before Chemosh” (Gibson 1971, No. 16, ln. 17-18). Rather than just defeat a nation through reclaiming their cities and killing inhabitants, Mesha confirmed his success by bringing Yahweh's religious items before Chemosh. In doing so, Mesha ritually subordinated Yahweh to Chemosh. Such an action illustrates how his attempt to establish political rule over ancient Israel was accomplished through means of subordinating the primary deity of ancient Israel to the primary deity of Moab.

Conclusion

Though one of thousands of ancient inscriptions, the Moabite Stone is one of the longest inscriptions. As such, it can be extremely useful for reconstructing history. Nonetheless, we should be careful to recognize that even inscriptions have both implicit and explicit biases. These biases can result in a skewed understanding of history. As such, it must, as with any inscription, be corroborated with other data. Moreover, our readings of such ancient inscriptions should be careful not to strongly distinguish between “politics” and “religion.” As has been demonstrated, these categories were more intertwined in the ancient world than they are in our own world.