The Moche civilization (also known as the Mochica) flourished along the northern coast and valleys of ancient Peru, in particular, in the Chicama and Trujillo Valleys, between 1 CE and 800 CE. The Moche state spread to eventually cover an area from the Huarmey Valley in the south to the Piura Valley in the north, and they even extended their influence as far afield as the Chincha Islands. Moche territory was divided linguistically by two separate but related languages: Muchic (spoken north of the Lambayeque Valley) and Quingan. The two areas also display slightly different artistic and architectural trends and so the Moche state may be better described as a loose confederacy rather than a single, unified entity.

The Moche were contemporary with the Nazca civilization (200 BCE - 600 CE) further down the coast but, thanks to their conquest of surrounding territories, they were able to accumulate the wealth and power necessary to establish themselves as one of the most unique and important early-Andean cultures. The Moche also expressed themselves in art with such a high degree of aesthetics that their naturalistic and vibrant murals, ceramics, and metalwork are amongst the most highly regarded in the Americas.

Moche

The capital, known simply as Moche and giving its name to the civilization which founded it, lies at the foot of the Cerro Blanco mountain and once covered an area of 300 hectares. Besides urban housing, plazas, storehouses, and workshop buildings, it also has impressive monuments which include two massive adobe brick pyramid-like mounds. These monumental structures, in their original state, display typical traits of Moche architecture: multiple levels, access ramps, and slanted roofing.

The larger 'pyramid' is the Huaca del Sol, which has four tiers and stands 40 metres high today. Originally it stood over 50 m high, covered an area of 340 x 160 m, and was constructed using over 140 million bricks, each stamped with a maker's mark. A ramp on the north side gives access to the summit, which is a platform in the form of a cross. The smaller structure, known as the Huaca de la Luna, stands 500 metres away and was built using some 50 million adobe bricks. It has three tiers and is decorated with friezes showing Moche mythology and rituals. The entire structure was once enclosed within a high adobe brick wall. Both pyramids were constructed around 450 CE, were originally brightly coloured in red, white, yellow, and black, and were used as an imposing setting to perform rituals and ceremonies. The Spanish conquistadors later diverted the Rio Moche in order to break down the Huaca del Sol and loot the tombs within, suggesting that the pyramid was also used by the Moche for generations as a mausoleum for important persons.

Buildings excavated between the two pyramid-mounds include many large residences with courtyards enclosed by walls. The fields around the site are laid out in a regular grid pattern of small rectangular plots often with a small adobe viewing platform, which suggests some sort of state supervision and control by the elite (Kuraka) class. Moche agriculture benefitted from an extensive system of canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts, so that the land could support a population of around 25,000.

Other Moche sites include a pilgrimage centre at Pacatnamú, a mountain top site above the Jequetepeque River and actually used from the Early Intermediate Period (c. 200 BCE). There were also administrative centres at Panamarca - where there is another large adobe brick mound, this time with a switch-back ramp leading to the top of the structure - and at Huancaco in the Viru Valley and Pampa de Los Incas in the Santa Valley.

Moche Religion

Moche religion and art were initially influenced by the earlier Chavin culture (c. 900 - 200 BCE) and in the final stages by the Chimú culture. Knowledge of the Moche pantheon is sketchy, but we do know of Al Paec the creator or sky god (or his son) and Si the moon goddess. Al Paec, typically depicted in Moche art with ferocious fangs, a jaguar headdress, and snake earrings, was considered to dwell in the high mountains. Human sacrifices, especially of war prisoners but also Moche citizens, were offered to appease him, and their blood was offered in ritual goblets. Si was considered the supreme deity, as it was this goddess that controlled the seasons and storms that had such an influence on agriculture and daily life. In addition, the moon was considered even more powerful than the sun because Si could be seen both at night and during the day. It is also interesting that murals and such finds as the intact tomb of the priestess known as La Senora de Cao illustrate that women could play a prominent role in Moche religion and ceremony.

Another deity who frequently appears in Moche art is the half-man, half-jaguar Decapitator god, so-called because he is often represented holding a vicious looking sacrificial knife (tumi) in one hand and the severed head of a sacrificial victim in the other. The god may also be depicted as a gigantic spider figure ready to suck the life-blood from his victims. That such scenes mirror real life events is supported by archaeological finds, such as those at the foot of the Huaca de la Luna where skeletons of 40 men under 30 years of age show evidence that they were mutilated and thrown from the top of the pyramid. The bones of these skeletons display cut marks, limbs were ripped out of their sockets, and jaw bones are missing from severed skulls. Interestingly, the bodies lie above soft ground caused by heavy El Nino rains, which suggests the sacrifices may have been offered to the Moche gods in order to alleviate this environmental disaster. Ceremonial goblets have also been discovered which contain traces of human blood, and tombs have revealed costumed and be-jewelled individuals almost exactly like the religious figures depicted in Moche murals.

Moche Art

Many fine examples of Moche art have been recovered from tombs at Sipán (c. 300 CE), San José de Moro (c. 550 CE), and Huaca Cao Viejo, which are amongst some of the best preserved burial sites from any Andean culture. The Moche were gifted potters and superb metalworkers, and finds include exquisite gold headdresses and chest plates, gold, silver, and turquoise jewellery (especially ear-spools and nose ornaments), textiles, tumi knives, and copper bowls and drinking vessels. Fine pottery vessels were usually made using moulds, but each was individually and distinctively decorated, typically using cream, reds, and browns. Perhaps the most famous vessels are the highly realistic portrait stirrup-spouted pots. These are considered portraits of real people, and several examples could be made depicting the same individual. Indeed one face - easily identified by his cut lip - appears in over 40 such pots.

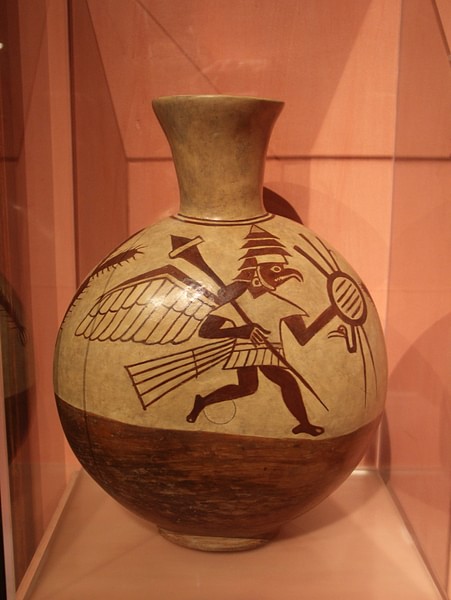

Pottery shapes and decorations did evolve over time and became more and more elaborate, although conversely, themes became less various in later Moche pottery and art in general. One of the most distinctive styles created by the Moche uses silhouette figures embellished with fine line details very similar to Greek black-figure pottery. Ceramic effigy figures are also common, especially of musicians, priestesses, and captives.

Popular subjects in Moche art - as seen on wall paintings, friezes, pottery decoration, and fine metal objects - include humans, anthropomorphic figures (especially fanged felines), and animals such as snakes, frogs, birds (especially owls), fish, and crabs. Whole scenes are also common, especially religious ceremonies with Bird and Warrior Priests, shamans, coca rituals, armoured warriors, ritual and real warfare with their resulting captives, hunting episodes, and, of course, deities - notably scenes showing night skies across which crescent boats carry figures such as Si. Many of these scenes are rendered to capture narratives and, above all, action; figures are always doing something in Moche art.

Sipán & Pampa Grande

In c. 550 CE the Moche canal systems and agricultural fields became covered in sand (blown inland from the coast where it had been deposited by erosive flooding from the valleys), and the population left the area, resettling further north in the Lambayeque Valley, notably at the sites of Sipán and Pampa Grande. The move may also have been precipitated by the expansion of the Huari based in the highlands of central Peru. At Sipán some of the best preserved and richest tombs in the Americas have been discovered, including the famous 'Warrior Priest' tomb with its outstanding precious metal objects such as a gold mask, ear-spools, bracelets, body armour, sceptre, ingots, and magnificently crafted silver and gold peanut necklace.

The site of Pampa Grande covered 600 hectares and included the once 55 metre high Huaca Fortaleza ritual platform. Reached by a 290-metre ramp the summit had a columned structure containing a mural of felines. However, after 150 years of occupation the site was also abandoned, once again, probably due to a combination of climatic factors such as an extended period of drought, Huari expansion, and internal strife as indicated by evidence of fire damage to many of the buildings.

![Moche Head [Pottery Vessel]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/c/p/360x202/9733.jpg?v=1599125404)