The Monmouth Rebellion of June-July 1685 involved James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (1649-1685), illegitimate son of Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), attempting to take the throne of his uncle James II of England (r. 1685-1688). Monmouth's ramshackle army was defeated by a professional Royalist army at Sedgemoor in Somerset on 6 July.

Although many Protestants did not want Catholic James II as their king, going so far as mounting an armed rebellion to dethrone him was a step too far for most. James had already promised his daughters and heirs would be brought up as Protestants, and so many were prepared to bide their time. The Duke of Monmouth was captured after the rebellion was quashed, and, despite pleading for his life, his uncle showed no mercy and had him executed. The king also ensured that hundreds of rebels or those suspected of supporting them were hanged, flogged or deported to the colonies for a life of hard labour.

The House of Stuart

When Charles II of England died without an heir in 1685, the crown was passed on to his younger brother who became James II of England (and James VII of Scotland). There had been another choice, though: James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (b. 9 April 1649), the illegitimate son of Charles II (although some modern historians question if Monmouth was his son at all). Monmouth became a favourite of his father who did acknowledge him as his own and who bestowed the dukedom upon the handsome youth in February 1663. This favouring did not stop the duke from trying to snatch the throne, or at least having a group of former English Civil War Roundhead veterans (Parliamentarians) plot in his name. The 1683 Rye House plot, named after a farmhouse in Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, attempted to oust Charles II by capturing the king and his brother James on their way home from the races at Newmarket to London. The poorly planned escapade failed thanks to a quirk of fate. A fire broke out at the racecourse, and the meet was cancelled, which meant the royals went home early and so missed their would-be abductors. The conspirators were arrested and executed, but Monmouth was dealt with leniently and only sent into exile in the Netherlands.

The historian N. Jones describes Monmouth as "a charming but weak chancer" (351). The strength of Monmouth's renewed claim in 1685 was really that he was a Protestant, while James II had converted to Catholicism in 1668 and his second wife, Mary of Modena (d. 1718), was also Catholic. Since the troubled reigns of the Tudors, England had been a Protestant country, but there were still many Catholics who dreamed of reinstating their faith as the official one of the kingdom. The two houses of Parliament were also divided, with the "Whigs" in the lower house eager to promote Protestantism and the "Tories" in the House of Lords keen to keep the Stuart line of succession as it should be. In 1679, James had even been excluded by Parliament from the succession because of his faith, but his brother had had him reinstated. There was the condition that James ensure his two surviving legitimate children, Mary (b. 1662) and Anne (b. 1665) – both from his first marriage – be brought up as Protestants.

Protestant Rebellion

King James had at least played down his Catholic sympathies in his coronation ceremony when he eliminated the communion part. Still, the rumours would not go away that he intended to return England to Catholicism. There were even wild claims that the queen was actually the daughter of a pope, such was the atmosphere of suspicion.

In May 1685, the Earl of Argyll led an anti-Catholic uprising in Scotland. Principally involving the Protestant Campbells, of which Argyll was the leader, the uprising was small and fizzled out after Argyll was captured while marching to Glasgow. With Protestant exiles in the Netherlands involved in both the Argyll and Monmouth rebellions, it is likely they were planned to simultaneously challenge James II in the north and south.

Monmouth had gathered around him around 80 exiles who collectively deluded themselves into thinking they might gain wide support of Protestants in England. To increase his claims of legitimacy, Monmouth claimed, or more accurately encouraged the rumour, that his father had actually married his mother Lucy Walter in The Hague and evidence of this could be found in a mysterious black box. Monmouth described James II as an absolute tyrant and his Parliament as full of sycophants.

In June 1685, the group of rebels sailed three ships to Lyme Regis in Dorset and recruited what followers they could in the southwest of England. This area of the kingdom was selected because it was a stronghold of Protestantism and Republicanism (Monmouth promised a less authoritarian brand of monarchy). They managed to get 3-4,000 fighting men, but they were an unhealthy mix of amateurs, adventurers, and farmhands. They were all of the lower classes, but amongst them was one Daniel Defoe (c. 1660-1731), future author of Robinson Crusoe. Monmouth's cavalry force was little better than his infantry, composed as it was of inferior horses. Neither was there any evidence of a sympathetic uprising elsewhere such as in London. Nevertheless, there was no turning back now, Parliament had even put a £5,000 bounty on the duke's head. What became known as the Monmouth Rebellion was underway.

Battle of Sedgemoor

Monmouth's shabby-looking army did well at first, defeating the county militia in several minor battles. London seemed too big a target for the rebels, and so Monmouth opted to try and take the important port of Bristol instead. Then they were met by a professional royal army on 6 July at Sedgemoor outside Bridgewater in Somerset, and it was an entirely different story from the skirmishes with local militia. The Royalists were led by John Churchill, the future Duke of Marlborough, although command on the battlefield was in the hands of the Earl of Feversham. Monmouth hoped to use surprise to his advantage, and so he initiated the attack. Unfortunately for the rebels, a water-filled ditch barred their way and hampered their progress to such an extent that Feversham's force was alerted. The Royalists made short work of the rebel cavalry, and when that fled the moor, the rebel infantry was massacred. Around 500 were killed and 1,500 taken prisoner.

Monmouth himself managed to escape the carnage early on by fleeing on horseback. The duke hid in the 'Rhines', the wild marshlands of Somerset. Moving towards the south coast and on through the New Forest, Monmouth was obliged to forage for food for a week. Finally, the man who would be king was caught sleeping in a ditch, he was disguised as a shepherd, and his pockets were full of peas.

Vengeance

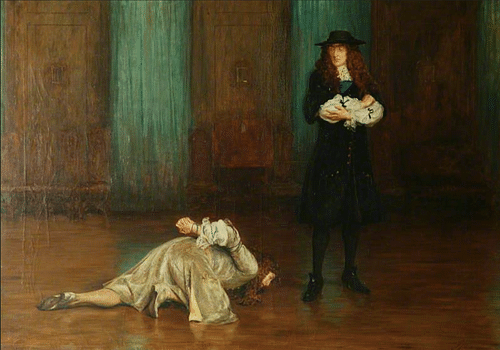

Monmouth begged an audience with his uncle to seek his forgiveness, but although the king granted such a meeting where Monmouth threw himself at his sovereign's feet, James would not be moved. Monmouth offered to disclose the names of his fellow rebels, but the king was determined to be done with his challenger. Obviously guilty of treason and so declared by Parliament, no trial was needed according to English law. Monmouth's day of execution was set as 15 July. The fateful day was St. Swithun's Day, named after the 9th-century bishop and great miracle worker, but there was to be no miraculous reprieve for Monmouth. The execution was one of the clumsiest beheadings on record that required five swings of the axe, and that despite Monmouth tipping Jack Ketch, his executioner, six guineas to do a decent job. Indeed, the axeman gave up halfway through, and the grisly task had to be finished using a butcher's knife. Monmouth's corpse was taken from Tower Hill, his head was reattached to his body and then buried under the floor of the Church of Saint Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London.

Many of the ringleaders of the rebellion were also sentenced to death. In all, 333 people received the death sentence, many of them executed by hanging and, while still conscious, eviscerated. Some 850 rebels were transported for a significant term of hard labour (indentured servitude) on Caribbean plantations. Anyone with even the remotest connection to the rebellion – men, women, and children – received lesser punishments like floggings. Such was the severity of the Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys' rulings, the cases became known collectively as the 'Bloody Assizes', and they did nothing for the king's popularity.

Aftermath

After the rebellion, James began to turn more overtly pro-Catholic. He appointed Catholics in key positions in the government, courts, navy, and army; even university appointments took on a distinct Catholic bias. The king also ignored laws, extended others, and waived sentences when they applied to Catholic individuals he favoured, what became known as his Dispensing and Suspending powers. There were formal measures to improve the status of Catholics such as the April 1687 Declaration of Indulgence (aka Declaration of the Liberty of Conscience), which actually improved religious toleration for all faiths. Then a prominent trial of the Archbishop of Canterbury and several other bishops backfired and made the king even more unpopular.

When the king finally had a son born in June 1688, James Francis Edward, Protestants saw the very real possibility that the next monarch would be a Catholic, too. Consequently, Protestant William of Orange, a grandson of Charles I of England and husband of James II's daughter Mary (m. 1677), was invited to invade England and become king. This he did remarkably easily without any bloodshed since King James decided to flee to France. The Prince of Orange became William III of England (and William II of Scotland, r. 1689-1702), and he ruled jointly with his wife, now Queen Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694). This was the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and although Parliament grew in its powers with respect to the monarchy, the 'revolution' achieved by peaceful means what the Monmouth Rebellion had failed to do: ensure the permanent continuance of a Protestant monarchy for England, Scotland, and Ireland.