The motte and bailey castle was an early form of medieval fortification especially popular with the Normans in northern France and Britain during the 11th century CE. A single tower was built on (or partially within) the motte or earth mound while a courtyard area or bailey at the base was protected by a wooden palisade and an encircling outer ditch. Relatively quick to build, the height of the mound made the tower difficult to attack while the wall offered a place of refuge from opportunist raiders. For these reasons, the motte and bailey castle was especially useful in freshly conquered territories where the native population was still hostile to their new overlords. As stone resisted fire better than wood and defensive designs improved, castles evolved into more permanent structures with stone circuit walls and towers enclosing a more impressive inner stone tower or keep (donjon).

Evolution & Design

The earliest form of fortified camp was a simple wooden palisade, perhaps with earthworks, surrounding a camp (ringworks), sometimes with a permanent wooden tower in the centre. These had been common since Roman times and remained little-changed for centuries. Then, stand-alone wooden towers became a feature of defences in northwest France from the 9th and 10th centuries CE. These structures evolved into the more sophisticated motte and bailey castles, which were especially common in France and Norman Britain from the 11th century CE.

The castles consisted of a wooden wall, perhaps built on an earth bank, encircling an open space or courtyard (bailey) and a natural or artificial hill (motte) which had a wooden tower built in the centre of its flattened top, sometimes surrounded by its own wooden palisade. The tower ranged from a mere lookout tower or firing platform to the more substantial building used as a residence for the local lord. Some towers were built on stilts, presumably to save time and materials in their construction and to make them more difficult to scale. The motte was sometimes connected to the bailey by a type of bridge, but most had steps cut into their sides.

The whole castle structure was further protected by an encircling ditch, which could be with or without water. There was no specific design blueprint to follow as castles took advantage of local terrain and other factors, as the historian N. J. G. Pounds here notes:

Construction was influenced by local terrain and geology, by labour and materials, and by the random wishes and whims of an infinite number of people. (15)

With variations in dimensions, layout, towers, walls, and foundations, some castles had two mottes while some mottes had two or even three baileys. There is also sometimes the difficulty, given the lack of surviving structural remains, of distinguishing a fortified private home built on a mound from a castle used as an administrative centre. The latter were generally larger and the bailey therein typically contained domestic buildings, stores and supplies, workshops, stables and, crucially, a well.

The roughly circular mottes, rising to a height of anywhere from 4.5 to 9 metres (15-30 feet) and ranging from 25 to 100 metres (80-330 ft) across, were built using the earth excavated from the ditch or utilised natural rises or perhaps even more ancient fortification sites. There is archaeological evidence that some mottes were built up after the tower had been built and so were used to protect the base of the structure and/or make it more stable rather than give it extra height. Additional solidity was provided in some mottes by riveting in timber stakes or facing them with wooden boards or stone slabs.

Purpose

Castles emerged as the feudal system took shape where a local lord and his knights ruled over an area of land farmed by peasants. Castles could offer protection as a last place of refuge and were useful as a visual symbol of the lord's power and wealth with respect to the local communities. Motte and bailey castles were typically built at frontier sites to prevent raiding. Other locations of strategic importance included river crossings, passes, coastal areas, next to important settlements and alongside old but still used Roman roads. As they were relatively quick to erect, a motte and bailey castle was sometimes even built by a force attacking a more substantial castle as a place of refuge from cavalry sorties by the besieged.

Advantages & Disadvantages

Motte and bailey castles, being made from timber and earthworks were relatively quick to build, taking only a few weeks or months, a distinct advantage in hostile and newly-conquered territories where recently subjugated tribes might launch revenge attacks on their new overlords or, at the very least, proved reluctant to be conscripted into their construction. In addition, this type of fortification did not require any particularly skilled labour or stones to be quarried and transported, which dramatically reduced their cost of construction.

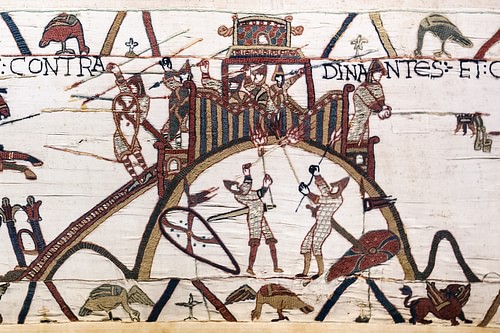

As they were largely made of wood, motte and bailey castles were susceptible to fire during an attack, as can be seen in various scenes from the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the 11th-century CE Norman conquest of Britain and events leading up to it. Motte and bailey castles did not resist the weather well either, with mounds and timber structures degrading over time and even causing the collapse of towers. For these reasons, more permanent stone castles, despite their huge expense and the years needed to build them, were commissioned as a safer, longer-lasting, and more comfortable residence by those who could afford them.

Decline & Reuse

As castle fortification design developed, motte and bailey castles were adapted to new needs and technologies of warfare. An outer wall was built of stone on top of the motte, and it is then known as a shell keep. Finally, by the 12th century CE, the main central tower also came to be built of stone, but not usually on the motte itself as that was not stable enough to use as a foundation for such a heavy structure. In many cases, the bailey became more fortified and more important than the motte, which was sometimes reduced in size or even built over.

Although many early castles were abandoned for more secure and comfortable stone castles, motte and bailey castles continued to be used and built into the 12th and 13th century because of their low cost. More common now, though, was the shell keep and new castles with innovations such as tower keeps enclosed by concentric circuit walls which incorporated round mural towers with heavily-fortified gates, all in stone. Such castles did not need to be built on a hill, although natural rock promontories remained a tempting location for castle architects throughout the Middle Ages.

Mottes were significant piles of earth, and although they were abandoned as fortress residences, they remained very visible features of the countryside for centuries after and are still around today in many countries. A good many mottes, too, found themselves included in country estates and were adapted as interesting features of landscape gardens from the 18th century CE onwards. Spiral walkways were added to reach their summits which, although lowered by weathering, still offered good views. Many had pavilions and summer houses added or even faked ruins built on them to add to the romance of the grounds and remind of the long history of the site.