The Mountain Meadows Massacre (11 September 1857) was a conflict between the Mormons (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and the wagon train of the Baker-Fancher party, who were traveling through Utah to California, resulting in the deaths of 120 emigrants of the wagon train. The event is featured in the 2025 TV miniseries American Primeval.

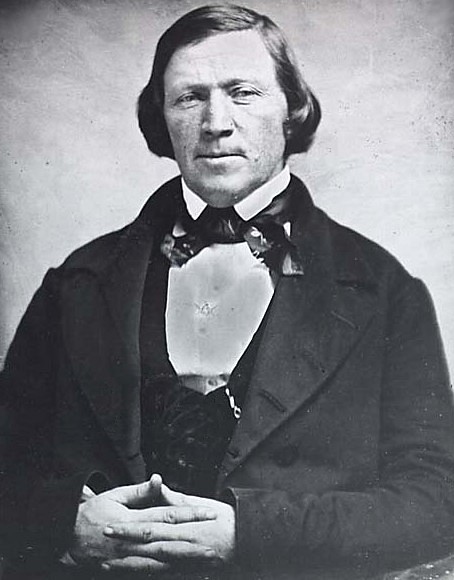

The massacre is the best-known and most infamous of the Utah War (1857-1858), an armed conflict between the Mormon community of the Utah Territory and the US government. The Mormons had migrated to the region after repeated persecution in the United States, including the execution of their founder, Joseph Smith (l. 1805-1844), in Carthage, Illinois, in 1844. In 1846, Brigham Young (l. 1801-1877), Smith's successor, led his people to the Utah Territory, then part of Mexico, to establish a religious community outside of US government jurisdiction. By the time they reached their destination (now known as Salt Lake City, Utah) the region had become part of the United States.

In 1857, President James Buchanan (served 1857-1861), sent US military to the Utah Territory to establish order, which was seen by the Mormons as an attempt to continue the persecution they had faced in the United States. Brigham Young, who had been appointed governor of the territory by President Millard Fillmore (served 1850-1853) in 1851, responded by declaring martial law and forbidding any US travelers from crossing the territory without a permit from his office.

The Baker-Fancher party, knowing nothing of Young's proclamation or the rising tensions, were on their way to California when they were attacked by Mormons disguised as Paiute Native Americans along with actual Paiute allies on 7 September 1857. The wagon train defended themselves for five days until they were lured out by promises of safe passage and massacred by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, resulting in the deaths of 120 men, women, and children above six years old.

The Mountain Meadows Massacre has been the subject of several works of non-fiction and fiction, most recently featured as the pivotal event in the miniseries American Primeval (2025), which, although it takes certain liberties with known historical events, is largely accurate in its depiction of the time period, the tensions in the region, and those associated with the 1857 massacre.

Mormon Migration West

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded by Joseph Smith in Fayette Township, New York, on 6 April 1830. In 1831, he moved the church to Ohio where he ran into trouble with the local authorities, who accused him of bank fraud. He then moved on to Missouri where non-Mormons rejected his teachings, eventually leading to the Mormon War of 1838. Smith then moved his congregation to Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1839, but by 1842, the church was again threatened by non-Mormons who objected to Mormon doctrine and practice, including the baptism of the dead and polygamy.

In 1844, while Smith was under arrest for inciting a riot, a mob stormed the jail in Carthage, Illinois, and killed him. His successor, Brigham Young, decided there was no place for the church within the confines of the United States and moved his people west in 1846 to the Utah Territory, which was then part of Mexico.

Utah War & the Baker-Fancher Party

By the time Young and his people arrived at what would become Salt Lake City in 1847, Mexico had ceded the region to the United States in the course of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), though ownership would not become official until 1848. The Utah Territory was formally recognized by the US Congress in 1850, and Young was later appointed governor.

He had petitioned Congress to recognize his community as an independent state (the State of Deseret), but this was rejected. In 1856-1857, Young initiated the Mormon Reformation, which encouraged members to reject the ways of non-Mormons, reminding them of past persecutions, and to rely only on each other. This led to widespread refusal to recognize United States officials in the region, eventually resulting in the Utah War. Young declared martial law, deployed his militia, and decreed that non-Mormons must have an official permit, authorized by his office of the church, to pass through the region.

Tensions became heightened in May 1857 when a Mormon leader, Parley P. Pratt, was murdered in Arkansas by the husband of a woman Pratt had taken as one of his many wives. The murder had nothing to do with Pratt's religious beliefs – it was simply the act of a jealous husband – but was interpreted by the Mormons of Utah as further persecution by non-Mormons.

The Baker-Fancher party, led by John Baker and Alexander Fancher, left Arkansas in April 1857 to settle in California. It is estimated there were more than 200 people in the wagon train when it set out, over 1000 head of cattle, and a significant number of horses. Some members of the wagon train split off before reaching Utah Territory, and historians estimate the number at 120-140 men, women, and children upon their arrival in the region. None of these people are believed to have known anything about the tensions between the Mormons and the United States government and had no knowledge of Young's decree of martial law or his requirement of a permit to cross Mormon territory.

They reached Salt Lake City in early August 1857, where they had planned on resupplying for the journey on to California, but the Mormons refused to trade with them, having been instructed by Mormon leader George A. Smith (l. 1817-1875) to stockpile supplies against the threat of armed conflict with US troops. War hysteria and a general distrust of non-Mormons also contributed to the decision to refuse trade with the Baker-Fancher party who then moved on to graze their cattle and rest at Mountain Meadows.

Rumors circulated that the Baker-Fancher party had made disparaging remarks about the church and had also appeared to be threatening. They were also understood to be in violation of Young's degree of martial law as they had no permit to travel through Utah Territory. Senior leaders of the Mormon militia (the Nauvoo Legion) met at Cedar City to decide how to respond to the wagon train. A messenger was sent on horseback to Brigham Young (as Utah had no telegraph system at the time) asking for his advice, but then the leaders of the Nauvoo Legion seem to have decided to act on their own or, according to some scholars, already had a clear directive from Young.

Mountain Meadows Massacre

The senior militia leaders, Isaac C. Haight (l. 1813-1886) and William H. Dame (l. 1819-1884), agreed with the council on sending the messenger to Young before acting, but then Haight sent word to one of his militia officers, John D. Lee (l. 1812-1877), to come to Cedar City. Lee responded dutifully, meeting Haight, and, according to Lee's 1877 confession:

Haight told me all about the train of emigrants…that [they] were a rough and abusive set of men. That they had, while traveling through Utah, been very abusive to all the Mormons they met. That they had insulted, outraged, and ravished many of the Mormon women. That the abuses heaped upon the people by the emigrants during their trip from Provo to Cedar City had been constant and shameful...that they had poisoned the water, so that all the people and stock that drank of the water became sick.

(225)

Lee also says that he asked Haight on whose authority he was acting in telling Lee these things and ordering an attack on the wagon train. According to Lee, Haight answered, "It is the will of all in authority", giving Lee to understand that Brigham Young himself approved of the action (Lee, 226). Lee then put the plan into motion.

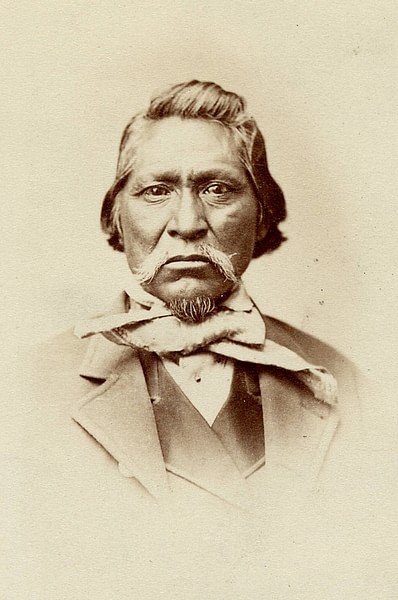

Efforts to drive the Paiutes against the emigrants had been abandoned, and, instead, members of the Mormon militia disguised themselves as Paiutes and then enlisted some actual citizens of that nation to participate, promising them part of the loot from the wealthy Baker-Fancher party.

On 7 September, they attacked the wagon train, which was at rest in Mountain Meadows. The Baker-Fancher group circled their wagons, quickly dug defensive trenches, and fought back. Seven of their members were killed on 7 September, and another 16 were wounded. The Baker-Fancher group held against the attack for five days before they began running out of ammunition, food, and water.

As the siege wore on, the Nauvoo Legion's leaders realized it would be impossible to allow any of the Baker-Fancher party to survive as they had, by this time, recognized White men among the attackers, and a report of armed Mormons assaulting a wagon train would surely bring more US troops to the region. On 11 September, John D. Lee approached the wagon train under a flag of truce along with a few others and offered the people safe passage to Cedar City, provided they turned over their weapons and livestock to the Paiutes, who, he said, had been their attackers. With no options, the Baker-Fancher party agreed, laid down their weapons, and abandoned the safety of their wagons.

The party was divided into adult men, who were escorted by an armed guard, and women and children. At a given signal (sometimes cited as "Do Your Duty!"), the Mormon militia shot all the men dead. The women and children were then killed with rifles, knives, and tomahawks. Scholar Will Bagley describes the massacre:

Major John Higbee [of the Nauvoo Militia] marched the men to "a smooth open space on the west side of the road and a patch of oak brush on the east. Higbee fired a shot and gave the crucial order, "Halt! Do your duty!" At the command, the guards turned and shot down the men…Each part of the field witnessed its special horrors…The women and children "were overtaken by the Indians, among whom were Mormons in disguise." Painted Saints and Paiutes gave "hideous, demon-like yells" as they "rushed past to slay their helpless victims…four-year-old Nancy Huff recalled "I saw my mother shot in the forehead and fall dead. The women and children screamed and clung together. Some of the young women begged the assassins after they had run out on us not to kill them, but they had no mercy on them, clubbing their guns and beating out their brains.

(146-147)

17 children under the age of six were spared as they were considered too young to tell anyone what they had seen. The bodies were hastily buried in shallow graves, and the livestock and possessions of the Baker-Fancher party were taken by the attackers and later sold off to fellow Mormons. The 17 children were turned over to Mormon families who, according to some reports, seem to have treated them poorly.

Aftermath & Investigation

All the participants in the massacre were sworn to secrecy, but, as scholar Sally Denton notes, there had to be some explanation given for the deaths of 120 emigrants and the looting of their wagon train:

After the fact, there was great uncertainty among Mormon leaders about how the crime would be viewed, both by the Gentile world and by the Mormons themselves, despite the earlier efforts to demonize the Fancher-Baker party. Now, the church hierarchy had to redouble its efforts to castigate the Paiute Indians, establishing a clear motive for why they could be said to have perpetrated the crime. To serve that end, the myth of the "poisoned springs" was invented.

(156)

The Mormons had earlier spread rumors that the Baker-Fancher party had been hostile and provocative in Salt Lake City (for which there was absolutely no evidence), and now the story Haight was said to have told Lee about the poisoned water making Mormons sick was spun into a new version of a poisoned a stream that had caused the deaths of some Pahvant Indians, who had then avenged these deaths in the attack. Chief Kanosh (l. 1821-1884) of the Pahvant band of the Ute nation, who had close ties to the Mormon community, rejected this story outright. Denton writes:

The story was ultimately discredited by military and other government investigators, and dismissed by various journalists and historians, but the Mormons tenaciously kept the fiction alive. For without the poison tale, the credibility of Indian hostility toward the emigrants completely dissolved, and with it a motive for the atrocity. Indian leaders themselves denied involvement just as vehemently, claiming any who participated were hired assassins and renegade mercenaries who had been promised payment in clothing, guns, and cattle by the Mormons.

(156)

Brigham Young, who is said to have responded to the message from Cedar City with instructions to leave the Baker-Fancher party alone (a message that, if sent, arrived too late) launched an investigation into the incident, placing Mormon leader George A. Smith – the same who had encouraged his fellow Mormons not to trade with the Baker-Fancher party – in charge. Smith concluded, by June 1858, that the Mountain Meadows Massacre was the work of Paiute Indians responding to the poisoning of their water by the emigrants.

The Utah War delayed any formal investigation by US authorities until May 1859 when Major James Henry Carleton (l. 1814-1873) arrived. Carleton concluded that the Mormons were responsible for the massacre. He and Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, helped reunite the 17 children kept by the Mormons with their families back in Arkansas. Bagley writes:

Reports on the condition of the rescued children contrast sharply. James Lynch charged the children "were in a most wretched and deplorable condition…with little or no clothing, covered in filth and dirt, they presented a sight heart-rending and miserable in the extreme." James Carleton railed against the "fiends" who "dared even to come forward and claim payment for having kept these little ones barely alive" [but] James Forney said, "I feel confident that the children were well cared for whilst in the hands of these people."

(237)

Reports from the children themselves also varied, but the one constant was that they could all identify their mothers' jewelry worn by Mormon women, notably the wives of John D. Lee, and their fathers' horses in Mormon stables.

Arrest warrants were issued for Isaac C. Haight, John Higbee, and John D. Lee, but all fled the territory, Lee going to Arizona where he established Lee's Ferry. The American Civil War (1861-1865) prevented further measures against the perpetrators but, in 1871, Philip Klingensmith, one of the participants in the massacre, who had since left the church, provided the authorities with an eyewitness account of the event and agreed to testify in court. Even so, Haight, Higbee, and the others could not be found, and so John D. Lee, easily located at Lee's Ferry, was the only one brought to trial, found guilty, and executed by firing squad in 1877 at the site of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. None of the others involved were ever brought to justice.

Conclusion

At his trial, John D. Lee claimed he was merely a scapegoat for those in authority who had ordered the attack on the wagon train. The church rejected his claims, however, maintaining that, whatever Lee had done, he had acted on his own and had enlisted the aid of the Paiutes in the massacre of the Baker-Fancher party. Scholar Juanita Brooks writes:

It seems that, once having taken a stand and put forth a story, the leaders of the Mormon church felt that they should maintain it, regardless of all the evidence to the contrary. In their concern to let the matter die, they [did] not see that it can never be finally settled until it is accepted as any other historical incident, with a view only to finding facts.

(217)

On 11 September 2007, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints finally let go of the official story they had been telling for the past 150 years and formally took responsibility for the Mountain Meadows Massacre, issuing an apology to the descendants of the young survivors of the Baker-Fancher party and to the Paiutes they had consistently tried to blame for the slaughter.

In 2011, the descendants of the survivors and members of the church joined together again at the designation of Mountain Meadows as a National Historic Landmark. The site includes several monuments in honor of those who were killed there, including the first one raised by Major Carleton in 1859 over the mass grave of 34 of the victims of the Mountain Meadows Massacre.