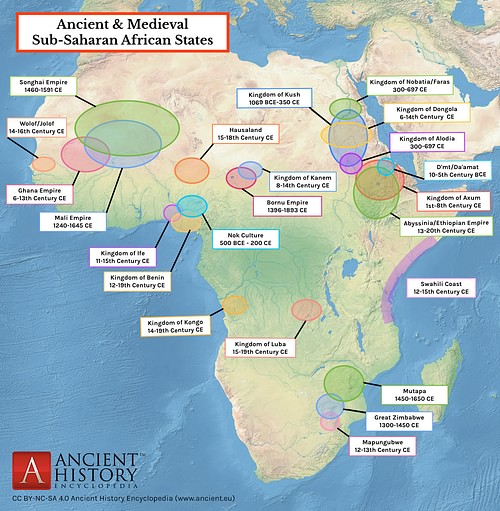

Mutapa (aka Matapa, Mwenemutapa, and Monomotapa) was a southern African kingdom located in the north of modern Zimbabwe along the Zambezi River which flourished between the mid-15th and mid-17th century CE. Although sometimes described as an empire, there is little evidence that the Shona people of Mutapa ever established such control over the region. Prospering thanks to its local resources of gold and ivory, the kingdom traded with Muslim merchants on the coast of East Africa and then the Portuguese during the 16th century CE. The kingdom went into decline when it was weakened by civil wars, and the Portuguese conquered its territory around 1633 CE.

Great Zimbabwe Decline

By the 15th century CE, the kingdom of Great Zimbabwe (est. c. 1100 CE) was in decline and any links with the lucrative coastal trade of the Swahili coast had ceased. This may be because gold deposits had run out in the territory controlled by the kingdom. Additional factors may have included overpopulation, overworking of the land, and deforestation, leading to food shortages which were perhaps brought to crisis point by a series of droughts.

By the second half of the 15th century CE, the Bantu-speaking Shona peoples had migrated a few hundred kilometres northwards from Great Zimbabwe to a land where they displaced the indigenous pygmies and smaller tribes who fled to the forests and desert. The exact relationship between Great Zimbabwe and Mutapa is not known other than that archaeology has shown both kingdoms had very similar pottery, weapons, tools, and luxury manufactured goods like jewellery.

The Shona thus formed a new state, the kingdom of Mutapa, from around 1450 CE, although it may well have been a case of the Zimbabwe ruling elite changing capital rather than a general population movement from the south. The founder and first Mutapa king was Nyatsimba Mutota. According to Shona oral tradition, Mutota had been sent to investigate the land around the north bend of the Zambezi River and he came back with the glad tidings that it was plentiful in salt and wild game. The second king, Mutota's son Nyanhehwe Matope, would expand the kingdom even further, capturing both land and cattle.

The Mutapa Kingdom

The kingdom of Mutapa is sometimes, despite the lack of evidence of an administrative apparatus, flatteringly described as the Mutapa Empire. The kingdom would, however, nominally control territory south of the Zambezi River bend in what is today's northern Zimbabwe and a small slice of southern Zambia. Here in the valley of Mazoe, a tributary of the Zambezi, the kingdom prospered and was able to subjugate, or at least exert some form of dominance over neighbouring kingdoms like the Mannyika, Uteve, and Mbara. Here there were also alluvial and reef gold deposits but not as rich as those once found at Great Zimbabwe. Beyond these areas, it is not known where precisely the borders of the Mutapa kingdom extended to except that its heartland was the Mukaranga region.

Monarchs ruled over a population of warriors who were also farmers and cattle-herders and who fought for the ruling elite in campaigns against rival tribes and chiefdoms. Initially, this arrangement worked well but rulers either did not or could not impose any form of administrative apparatus across their kingdom so that its unity, and indeed, survival, very much depended on the personality and talents of particular rulers. By appointing their own family members as regional governors and not creating any institutions of local government, whenever a chief died so too did the wholly centralised state apparatus. His successor had to then balance the difficulties of appeasing his own loyal followers and those powerful males of his predecessor's regime. A result was frequent civil wars between the king and those governors not keen to give up their power. Around 1490 CE the southern part of the kingdom split off to become the kingdom of Changamire, which would prosper into the 18th century CE.

Kings & Government

The chiefs or kings of the Shona held the royal title Mwene Mutapa, meaning either 'lord of metals' or 'master pillager' and they were, too, the religious head of the kingdom. They wore or carried as their badge of office a hoe and spear made of gold and ivory. Kings lived in an enclosed compound with separate buildings for the queen and another group for royal attendants. The latter group typically consisted of males under 20 years of age who came from the families of subjugated tribal chiefs and whose presence guaranteed compliance with Mutapa rule. When these young males were of the age to become warriors, they were sent home and given parcels of land or their own regions to govern in order to ensure their future loyalty.

Assisting the king, who ruled as an absolute monarch, were various officials such as the head of the army, chief musician, chief of medicine, a head spirit medium, and the royal doorkeeper. In matters of government, the king could call on the advice of nine ministers, the oddly named 'king's wives'. They were not all wives or even women. The queen was a member, and another was perhaps the sister of the king, but the others could be male ministers who had married into the royal family. The ministers ruled over their own estates and had some judicial powers such as imposing the death sentence on those found guilty of serious crimes. Ministers were served by female servants, much like the young men who served the king. The difference was that these maids could also be the concubines of the king. The senior wife of the king, known as the mazaira, did have real power and was responsible for relations with foreigners.

Trade

Gold, ivory, copper, animal hides, and slaves, acquired from the territories under the control of Mutapa, were exchanged for other goods such as embroidered textiles and glass beads from India at the great trade cities which occupied the coast of East Africa. Especially important to Mutapa was the outpost of Sofala, then controlled by the more northern city of Kilwa. These imported goods were then traded by Mutapa merchants for gold and ivory acquired from highland tribes. Trade was only ever in the hands of the ruling elite, and kings became rich from the profits, a situation which only enhanced their prestige and authority as they gave out gifts in return for loyalty.

Art & Architecture

Unlike at the other great southern African kingdom capitals of Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe, there were no local stone deposits at Mutapa with which to build impressive stone houses and walls. The capital was enclosed by a wooden palisade and buildings made using dried mud and wooden poles. Estimates of the capital's peak population, based on various Portuguese sources, are around 4,000 inhabitants. Other remains of structures include fortresses made on low rises which were improved with earthworks and protected by wooden palisades.

Polished pottery was produced, typically vessels of a bulbous form with a short neck. The pottery was burnished using graphite and red ochre and given simple incised decoration. Jewellery was described by European contacts and has been found at burial sites. These pieces include bangles, necklaces, and anklets made from long coils of copper, bronze, iron or gold wiring. Imported glass beads were used to add colourful decorative elements to locally acquired material such as ostrich shells, the whole worn as girdles and necklaces made up of thousands of small individual pieces.

The Portuguese & Decline

The Portuguese began to establish a presence and then control of the lucrative Swahili coast trade cites following the voyage of Vasco da Gama in 1498-9 CE when he went around the Cape of Good Hope and up the east coast of Africa. From 1530 CE attempts were made to establish trading markets (feiras) within Mutapa, to interfere in the kingdom's system of rule and even to convert the king and his people to the Jesuit faith, all of which were failures and only diminished the position of the king amongst his subjects. Another outside contact came from the Muslim Swahili merchants who travelled with their goods to Mutapa, although the Islamic religion was never adopted in the kingdom and people clung to their traditional Bantu animist beliefs and ancestor and fetish worship.

Around 1633 CE the Portuguese chose a more aggressive policy to control the region's resources and cut out their great rivals, the Swahili merchants. They attacked and conquered the kingdom of Mutapa, which was already weakened by damaging civil wars, causing its internal collapse. One positive consequence for posterity was that the Portuguese created the first written records about southern African peoples. Calling Mutapa - in the typically garbled European translation of African vocabulary - Benemetapa, the Portuguese explorer Diego De Goes made the following note: "The king of Benametapa lives in great style, and is served with great deference, on bended knee" (quoted in Ki-Zerbo, 6).

In the event, the Europeans soon lost interest when the gold they had hoped for proved to be far less in quantity than was being found elsewhere such as in West Africa or Inca Peru. Tropical disease was another factor in making any European presence in the region an ethereal and temporary one. What remained of Mutapa territory was then taken over by Batua, a long-time rival Shona kingdom, in 1693 CE. By the early 20th century CE the region was under control of the British South Africa Company, and two new states were formed in 1911 CE: Northern and Southern Rhodesia. The former would become the modern state of Zambia in 1964 CE while the latter eventually became Zimbabwe in 1980 CE.