The Mycenaean civilization flourished in the late Bronze Age from the 15th to the 13th century BCE, and their artists would continue the traditions passed on to them from Minoan Crete. Pottery, frescoes, and goldwork skillfully depicted scenes from nature, religion, hunting, and war. Developing new forms and styles, Mycenaean art would prove to be more ambitious in scale and range of materials than Cretan art and, with its progression towards more and more abstract imagery, go on to influence later Greek art in the Archaic and Classical periods.

Inspirations

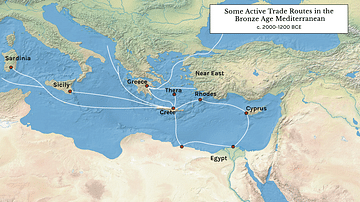

The Mycenaean civilization was based on mainland Greece but ideas and materials came via trading contacts with other cultures across the Mediterranean. Imported materials included gold, ivory (principally from the Syrian elephant), copper, and glass, while in the other direction went Mycenaean goods such as pottery to places as far afield as Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Levant, Anatolia, Sicily, and Cyprus.

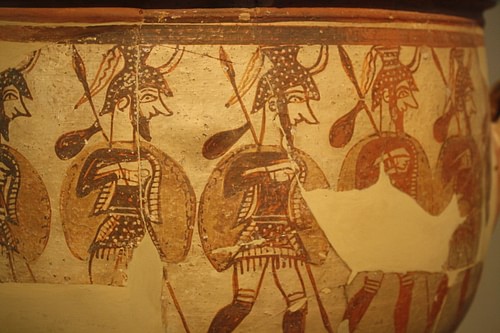

In art as expressed in fresco, pottery, and jewellery, the earlier Minoan culture on Crete greatly influenced Mycenaean art. The Minoan love of natural forms and flowing design especially was adopted by Mycenaean artisans but with a tendency to more schematic and less life-like representation. This new style would become the dominant one throughout the Mediterranean. Geometric designs were popular, too, as were decorative motifs such as spirals and rosettes. Pottery shapes are much like the Minoan with the notable additions of the goblet and the alabastron (squat jar) with a definite preference for large jars. Terracotta figurines of animals and especially standing female figures were popular, as were small sculptures in ivory, carved stone vessels, and intricate gold jewellery. Frescoes depicted plants, griffins, lions, bull-leaping, battle scenes, warriors, chariots, figure-of-eight shields, and boar hunts, a particularly popular Mycenaean activity.

Mycenaean Pottery

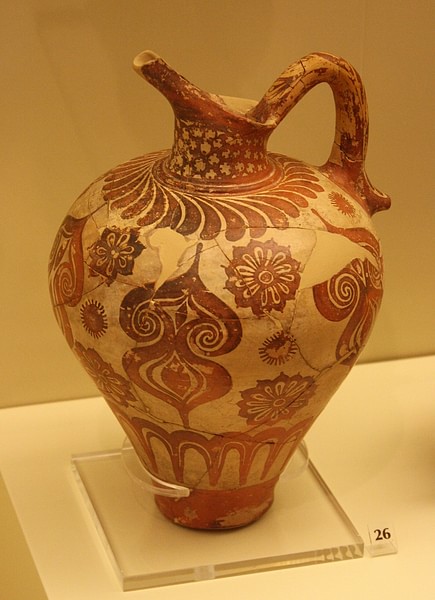

Early wheel-made Mycenaean pottery from mainland Greece has been described as 'provincial Cretan' which does convey the fact that although shapes and decorative styles were of Cretan origin, the final decoration was not quite as finely executed as in Minoan centres such as Knossos and Phaistos. Mycenaean clay was often superior in quality to Minoan, though, and was fired at higher temperatures. Some clay vessels were tin-plated too, perhaps to imitate more costly silver and bronze wares.

Popular Mycenaean vessel forms include stemmed cups, one-handled teacups, tankards and jugs with vertical strap handles and either spouts or cut-away necks. The most popular form was the stirrup jar, so called because the handle resembles a double stirrup. The centre of the handle was often decorated to look like a spout whereas the true spout was in fact to the side and separate from the handle. The second most popular vessel shape was the alabastron, a squat jar of various sizes, so named because the early examples were made from alabaster.

Clay sarcophagi had been widely used by the Minoans to bury their dead, and they usually took the form of either a chest with short legs or a bathtub. They were decorated in much the same manner as pottery vessels. Mycenaean Crete continued to produce them in great numbers. Clay was also used to make rhyta - vessels used for pouring libations and ceremonial drinking during religious ceremonies. These are most commonly in a conical form and are decorated as contemporary pottery vessels.

Like the Minoans, the Mycenaeans loved to paint sea life, especially octopuses and nautiluses. Designs also continued to fill all of the decorative surface and follow the contours of the vessel. Mycenaean pictorial scenes include chariots and human figures, something extremely rare in Minoan pottery. Sacral knots, double axes, and tusked helmets were popular subjects as were animals, birds, and griffins, often arranged heraldically and themselves decorated with pattern designs, possibly imitating contemporary textile designs. An excellent example of this technique can be seen in the bull and bird decorated vase from the British Museum, where the bodies are divided into sections, each decorated differently with dots, wavy lines, scales, crosses, or chevrons.

Gradually, representations became more stylistic and more symmetrical with not all of the decorative space filled, leaving significant blanks, again, something rarely seen in Minoan pottery. Depictions of plants such as lilies, palms and ivy became more monumental, evolving into commonly employed motifs that were reserved principally for large jars. Designs on pottery eventually became so abstract that the original subject becomes almost unrecognisable. Another development is a preference for only a single motif design on each side of the vessel and a marked increase in the space left blank. An excellent example is the Ephyrean goblet, a stemmed, two-handled cup from Mycenae, which is decorated with a single large rosette on each face.

The pottery of the Mycenaean civilization, then, achieved its own distinctive decorative style which was strikingly homogeneous across Mycenaean Greece. The Mycenaean fondness for stylized and minimalistic linear designs would go on to influence the early pottery of Archaic and Classical Greece from the 9th century BCE.

Mycenaean Frescoes

Mycenaean frescos which decorated palace walls and other buildings were similar to those of Minoan Crete, with nature and marine life again being the subject of choice. Mycenaean artists, as with potters, favoured a more monumental effect and a greater preference for depicting religious ceremonies, processions, hunters and warriors. Unfortunately, examples of Mycenaean frescoes only survive in fragments. Those from Mycenae include a female figure in profile wearing a tight-fitting jacket and holding perhaps a necklace which is similar to the one she is wearing. A fragmentary fresco with a very similar subject was discovered at Tiryns. Another surviving example from Mycenae is the fresco of the figure-of-eight shields, which has shields which appear to be made of cow skin.

Mycenaean Sculpture

Clay figurines have been found at sites across the Mycenaean empire, dating from the 14th to 12th centuries BCE and remarkably similar in design. Highly stylized to the point of being almost unrecognisable as human forms, the figures are most commonly female and standing, probably representing a nature goddess. Often these figures have two arms raised or crossed in front of the chest, a long skirt, and a conical headdress. They are simply decorated with bold lines and sometimes jewellery is also painted on the figure using simple dots. From 1200 BCE clay animal figures, especially bovids, were also popular. Made on the wheel and with limbs and heads made by hand, they are likewise simply decorated with lines and dots. Figurines were also carved from bone and probably wood (which has not survived).

A head of possibly a sphinx in plaster with painted features is something of an enigma but, nevertheless, is firm evidence that Mycenaean artists were interested in sculpture even if few examples survive. It dates to the 13th century BCE and was discovered at Mycenae. Ivory figures are rare but an outstanding piece is the two goddesses and child figure group from Mycenae. Ivory boxes and panels to attach to furniture are more numerous, and these often carry representations of sphinxes. Several limestone tomb markers have been excavated, and these are carved with relief designs typical of those found in other art works. One of the largest scale pieces of Mycenaean sculpture is the famous lion gate of Mycenae. Carved from limestone the pair of lions sit either side of a column and date to c. 1250 BCE. They are an excellent example of a common feature of Mycenaean art: a Minoan subject (in this case one seen in their seals) that is realised on a scale and in a form entirely Mycenaean.

Finally, and amongst the most impressive of all Mycenaean art works, there are the gold rhytons and death masks. One of the finest examples of the former is that in the form of a lion's head now in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The death masks were placed over the face of the deceased, and although not exactly portraits, they are each different. The most famous is undoubtedly the so-called 'Death Mask of Agamemnon' although, dating to the mid-16th century BCE, it is four centuries too early to be in the same time frame as Homer's king of Mycenae.

Mycenaean Jewellery

Mycenaean jewellers used gold, glass, faience, precious and semi-precious stones (e.g. carnelian, agate, and rock crystal), and amber to produce necklaces, pendants, rings, earrings, pins, brooches, and diadems. The full range of metalworking techniques was employed and even enamelling which the Minoans had not mastered. Glass beads were shaped, carved, and made from moulds.

Like the Minoans before them, Mycenaean artists became expert engravers and created miniature masterpieces on rings and seals. Early examples follow Minoan traditions of religious scenes and mythological creatures or hunting animals. Later examples show the stylized flowers and plants seen in pottery decoration, and the form is different, small squares of gold being typical. One of the finest rings is from Tiryns and shows a seated goddess being approached by a procession of four demon-like creatures bearing offerings.

Another medium for the engraver's art was the bronze blades of swords and daggers which show scenes of mythology and hunting rendered in inlaid gold and silver. Finally, fine gold work is exquisitely represented in several surviving gold cups. The finest are two examples from Vapheio, decorated with embossed scenes of men attempting to capture bulls. Both are in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

Legacy

Mycenaean artistic influence is perhaps most tangible in its pottery which was exported and imitated not only throughout the Aegean but also in places as far afield as Anatolia, Syria, Egypt, and Spain. There is also evidence that Mycenaean potters actually relocated and set up workshops abroad, particularly in Anatolia and southern Italy. Indeed, it may well be that designs of a Mycenaean origin introduced into these areas lived on to be reintroduced back to mainland Greece once the so-called Dark Ages had ended. The geometric pottery of the 8th century BCE certainly owed a great debt to the highly stylized pottery decoration so loved by the Mycenaeans. This, then, is perhaps the greatest contribution the Mycenaeans made to Western art: they carried the torch of artistic endeavour, passing it from the Minoans to Archaic Greece and so perpetuated the traditions which distinguished European art from the East.