Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) was the military advisor to the Plymouth Colony who traveled with the colonists (later known as pilgrims) aboard the Mayflower in 1620 CE. The colonists were made up of members of a religious separatist congregation, who referred to themselves as Saints, and others, not of their faith, whom they called Strangers. Standish was among the Strangers, though he was known by the Leiden congregation and seems to have been sympathetic to their vision; though there is no evidence he was ever a member of their group.

He was most likely born in Lancashire, England to a family of means but was disinherited, joining the army. He served in the Netherlands during the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648 CE) as a lieutenant in the English army (or perhaps a mercenary), fighting for the Dutch against Spain, and was promoted to captain. Around 1620 CE, he was contracted by the Leiden congregation as the military advisor for their expedition to the New World after they had first approached and then rejected Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) of Jamestown fame.

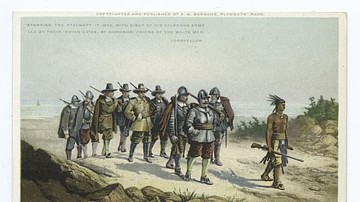

After arriving in Massachusetts, Standish was one of the signers of the Mayflower Compact, led or participated in explorations of the region to find a suitable spot for the colony, was among the few to survive the first winter, and was elected commander of the Plymouth Colony militia in February of 1621 CE, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. He was among the earliest settlers – probably the founder – of Duxbury, Massachusetts where he established a farm he lived on with his family and his Native American friend Hobbamock (d. c. 1643 CE), his comrade-in-arms.

He is among the most celebrated members of the Plymouth Colony, not only for the accounts of his activities as recorded by William Bradford (l. 1590-16567 CE) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE), the earliest chroniclers of the pilgrims, but through the historical fiction The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858 CE) by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (l. 1807-1882 CE) which established the story of the pilgrim settlers in United States' consciousness in the 19th century CE. Since then, Standish has continued to be celebrated in statuary, monuments, and place names in the United States and England, and his popularity remains undiminished.

The Leiden Congregation

Little is known of Standish's life prior to 1620 CE. All of the modern-day accounts regarding his birthplace and military service are based on scant evidence and speculation. His reputed birthplace of Lancashire, England is based on his will as is the claim that he was a member of the Standish family of Duxbury Hall (though this seems likely). His rank and role in the English army during the Eighty Years' War is equally uncertain, with some scholars claiming he was a mercenary and others an infantryman who rose through the ranks to captain. He is known to have served in the Netherlands between 1603-1620 CE, and it is clear he was known as Captain Myles Standish before 1620 CE.

Standish's relationship with the congregation of Leiden, the Netherlands is equally unclear. There is no indication he was ever a member, but he seems to have been on friendly terms with the separatists prior to 1620 CE. It is probable he was a separatist sympathizer, based on his later actions, but this is speculative. It is just as possible he joined the Mayflower expedition for the same reason many of the other Strangers did: in the hopes of improving their fortunes in the New World as they had seen others do at the colony of Jamestown, founded in Virginia in 1607 CE.

The Leiden congregation was a group of English separatists, led by their pastor John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE) who had left their homes in Scrooby, England, for the Netherlands in 1607 CE, fleeing persecution by King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE). James I was the head of the Anglican Church which, though Protestant, still retained aspects of Catholicism which the separatists objected to. In 1607 CE, the congregation of Scrooby was discovered by Anglican officials and persecuted as others had been and so relocated to Leiden where, in time, they met Standish. In 1618 CE, one of their most prominent members, William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE), published a tract critical of the Anglican Church, and orders were issued for his arrest.

The separatists, already trying to arrange an expedition to the New World, stepped up their efforts, sending two of their members – Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) and John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) – back to England to negotiate with the merchant adventurer Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE) for passage. Weston, a banker who matched potential colonists with investors, rented them a cargo ship, the Mayflower, while a friend (or possibly member), Captain Bloom, purchased them a passenger ship, the Speedwell, for their journey.

Rejection of Smith & Voyage

In preparing for the voyage, the congregation purchased the maps and works of Captain John Smith who had been among the original founders of Jamestown and was considered one of the most knowledgeable men in England on North America at this time. The separatists approached Smith as their guide and military advisor but decided against him on the grounds that he might dominate the group and was too expensive.

Having rejected Smith, they then asked Standish, and he accepted. In July of 1620 CE, Standish and his wife Rose boarded the Speedwell in Delfthaven, the Netherlands, and sailed to Southampton with the other passengers where they met up with the Mayflower. Weston, meanwhile, had hired some and invited others – not affiliated with the separatists – to help them establish a profitable colony in the New World (the so-called Strangers). Although the separatists objected to this stipulation, they had no choice but to accept the newcomers.

The two ships left Southampton together, but the Speedwell leaked continuously and, after a number of delays for repairs, had to be abandoned. Some of the Speedwell's passengers, including Standish and his wife, now crowded aboard the Mayflower and finally left on 6 September 1620 CE for the transatlantic crossing, which took them a little over two months.

Early Role in the New World

On sighting land, 9 November 1620 CE, Christopher Jones, Captain of the Mayflower (l. c. 1570-1622 CE), realized they were nowhere near where they should be. They were supposed to have landed above Jamestown in Virginia but were instead off the coast of New England. After trying and failing to follow the coast south, it was decided they would have to settle where they were. A number of the Strangers, recognizing that English law did not hold in this region and that the patent they had been issued carried no weight, argued that it would now be every man for himself, a claim the separatists recognized would seriously undermine their chances for survival.

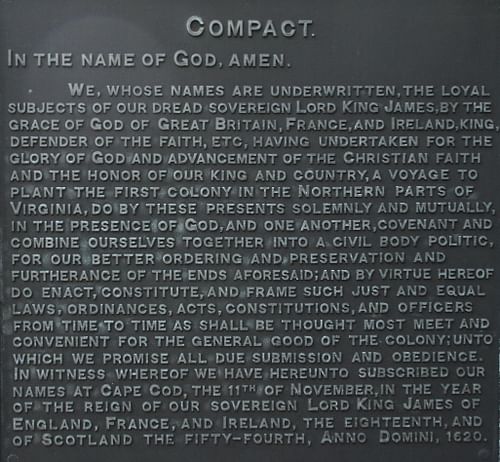

The Mayflower Compact was drawn up, in response to this threat, to establish a government and laws for the settlement – which Standish and 40 other men signed in agreement on 11 November 1620 CE – and only after that and the election of John Carver as the first governor were expeditions launched to find a place for the new colony. Standish, as their military consultant, led or participated in all of these.

Between mid-November and 21 December, Standish organized and led exploratory missions around present-day Cape Cod and the coast of Massachusetts, taking part in the so-called First Encounter with Native Americans when his party was attacked by the Nauset tribe in early December. Smith's maps, if they had them, seem to have been ignored since he clearly indicated in his work that the ideal location was present-day Boston which not only had a deep harbor to accommodate large ships for trade but freshwater rivers and lakes.

Instead, Standish and the others chose the site of Plymouth and began building the settlement there in late December 1620 CE. Between December 1620 CE and March 1621 CE, over half the passengers and crew would die of exposure, scurvy, malnutrition, and other diseases. According to Bradford, at one point only seven people remained healthy and devoted themselves to care for the others. Standish was among the seven and Bradford notes:

Myles Standish, their captain and military commander, to whom myself and many others were much beholden in our low and sick condition [was upheld by the Lord so that he] was not at all infected with sickness. (Book II. ch. 1)

Among the many who died the first winter was Standish's wife, Rose, and yet he continued to care for the sick. In the spring, the survivors continued to build the new settlement but still had no clear idea how they were going to survive until they were welcomed by the Native American Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653 CE) who introduced them to another Native American who spoke fluent English, Tisquantum (better known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE) who would teach them how to plant crops, fish, and hunt as well as introducing them to the chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, Ousamequin (better known by his title Massasoit, l. c. 1581-1661 CE), who would become their friend and ally. John Carver and Edward Winslow forged a mutually beneficial treaty with him prior to Carver's death in April 1621 CE, which was honored afterwards by Bradford, the second governor of the colony.

Native American Relations

Massasoit was a member of the Pokanoket tribe which had previously asserted control over others in the region to form his confederacy. These other tribes regularly paid him tribute and the warrior tasked with collecting this was Hobbamock who would become a lifelong friend of Myles Standish. In the summer of 1621 CE, Hobbamock informed the colony that Squanto and Massasoit had been kidnapped by Corbitant, chief of the Narragansett tribe, and Standish mobilized a force to rescue them, guided by Hobbamock. Squanto and Massasoit escaped before Standish's party reached the village, but his decisive action proved to the Native Americans that the Plymouth Colony would fully honor the treaty they had signed with Massasoit. Afterwards, a number of tribes came to pay tribute to Bradford and offer their own allegiance.

In the fall of 1621 CE, Massasoit and 90 of his warriors joined the colonists in the harvest feast which has since come to be known as the first Thanksgiving, Hobbamock and Squanto among them. The good relationship between the colonists and the natives would continue until the arrival in May 1622 CE of more settlers from England sent by Weston to establish a new colony since, thus far, he had been disappointed by the profits from Bradford's group.

These new colonists were all males, poorly equipped and provisioned, sent on a mission solely to turn a quick profit with no skills which would have helped them succeed. They established themselves north of Plymouth at a colony named Wessagussett, quickly consumed the supplies Bradford had given them, and began to steal food from the Native Americans. The colony degenerated further, worsening relations with the natives, until word reached Plymouth that an attack was planned on Wessagusset and, in order to avoid reprisals afterwards, Plymouth was also targeted.

Just prior to this, Standish had led a trading expedition to the native chief Canacum's village at Manomet and was in the middle of negotiations, with Hobbamock and Squanto at his side, when two warriors of the Massachusetts tribe arrived. One of these men, Wituwamat, showed off two knives he had used to kill European colonists as he spoke with Canacum, and the chief then ignored Standish and entertained Wituwamat more lavishly. Standish was known for his quick temper and angrily left the meeting, feeling he had been purposefully insulted by Wituwamat.

When word arrived at Plymouth of the impending attack on Wessagussett, Bradford agreed with Standish that a preemptive strike was in their best interests, and Standish was sent to deal with this. As it turned out, the attack was only a rumor and, when the party arrived at Wessagussett, there was no evidence of any trouble. Even so, Standish continued his mission, inviting Wituwamat and others into one of the houses in the settlement, ostensibly to discuss trade, where he killed them, cutting off Wituwamat's head and bringing it back to Plymouth where it was hoisted on a pole from the stockade.

Although Bradford had approved the mission and understood why Standish had acted as he had, he regretted the damage it caused to their relationship with the natives who, for a time, stopped all trade with the colonists. According to scholar Nathaniel Philbrick, Standish carried out the mission as though Wituwamat posed an actual threat to avenge the perceived insult received earlier. Massasoit approved of the action, however, encouraging other natives to resume trade and Hobbamock also supported Standish's decision which, owing to his high standing as Massasoit's right-hand man, carried considerable weight.

Courtship & Other Missions

Trade resumed with the Native Americans and Hobbamock came to live with Standish at the colony. In 1623 CE, the ship Anne brought more settlers to Plymouth, and among them was a woman named Barbara who became Standish's second wife in 1624 CE. Contrary to the popular poem The Courtship of Miles Standish by Longfellow, there is no evidence that Standish ever pursued Priscilla Mullins (l. c. 1602-1685 CE) as prospective wife nor that John Alden (l. c. 1598-1687 CE) ever acted as a matchmaker between them. Longfellow's poem was so successful, however, that it has often been repeated uncritically as having some basis in fact. John Alden and Priscilla Mullins would marry, however, (as in the poem) and their daughter Sarah would marry Standish's son Alexander in 1660 CE and have eight children, the ancestors of present-day descendants of Standish.

In 1625 CE, he was sent to England to negotiate new terms with Weston and the Virginia Company for paying off the debt the colonists still owed them for the 1620 CE expedition. Standish, owing to his fiery temper, failed at the negotiations and returned to Plymouth in 1626 CE. One of the members of the congregation, Isaac Allerton (l. c. 1586-1659 CE), was then sent to England and succeeded where Standish had failed. Allerton's negotiations allowed Bradford to distribute land beyond Plymouth to the colonists in 1627 CE, and Standish received a generous grant in Duxbury where he built a house and to which he retired in 1635 CE, remaining military consultant to the colony in an advisory capacity only.

One of his more controversial military actions the 1628 CE raid on the neighboring colony of Merrymount, founded by the liberal-minded lawyer Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE) who believed in assimilation with the native population, demilitarization of colonial efforts, and who encouraged joint celebrations and cohabitation between colonists and natives, which the Puritan separatists denounced as satanic. Standish took the village and arrested Morton, imprisoning him on an island off the coast to starve; he was later rescued by natives loyal to him and escaped back to England.

Conclusion

In his later years, Standish also served as the colony's treasurer and supervised the establishment of roads and divisions of land. Hobbamock and his family had moved with Standish to the farm and the two remained close friends until Hobbamock's death from European-borne disease c. 1643; Standish buried his friend on his farm. His relationship with Hobbamock is often cited as exemplifying Standish's respect for and good relations with the larger Native American community and this seems to be supported by the primary sources. Any engagement Standish undertook against the natives was pursued in the interests of preventing further violence on a larger scale, and in the raid to rescue Squanto and Massasoit, Standish insisted that the natives accidentally wounded in the raid be brought to Plymouth and cared for.

Standish's friendship with Hobbamock, defense of the settlement, and personal idiosyncrasies all made him an especially interesting figure to later writers and thinkers of the United States, especially after Longfellow's poem, and numerous stories and legends grew up around him, such as the one concerning his famous sword which was only drawn to do good and pursue justice. A 1921 CE article in the Virginia Chronicle states that the sword was carried in the Crusades and bears an inscription regarding its role in fighting against evil.

The description of the sword does not match the Standish Rapier presently on display at the Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth in the present day, but this is not surprising since stories of Standish's sword – like his courtship of Mullins – regularly made their way into “biographies” of Standish popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries CE. Up through the present day, Standish continues to capture the imagination of people, not only in the United States but around the world, as a paragon of the noble warrior and honorable defender of justice who was faithful to his vow in protecting the colony throughout his life.

He died at his farm, probably from cancer, on 3 October 1656 CE and was interred in the nearby cemetery (present-day Myles Standish Burial Ground) beneath a fieldstone marker. In 1891 CE, his remains were disinterred and reburied in a vault at the gravesite on which a monument to him was raised; since then he has continued to be honored through monuments, books, and in films as one of Plymouth's most enduring figures.