Mystery cults, or mystery religions, were ancient religious associations characterized by secrecy and initiation rites. They typically surrounded one primary deity, but some mystery cults venerated multiple deities in their rites. Members of mystery cults were required to maintain the secrecy of the cult's rituals and knowledge, which added to the cult's prestige.

Unlike many modern religions, mystery cults were not closed systems of faith. Initiation into a mystery cult did not entail forsaking all other gods, and initiates continued to participate in mainstream religious life. This made mystery cults a supplement to traditional Greco-Roman religious practices, as opposed to an alternative. Mystery cults fell out of fashion in Late Antiquity as Christianity became dominant. Some features of mystery cults parallel aspects of early Christianity, such as resurrection narratives, but these similarities are often exaggerated in popular history.

Etymology & Definition

Historians define mystery cults based on their shared features – such as secrecy and initiation rites – as well as the terminology used to describe them by ancient commentators. The Greek word for a mystery cult was "mysterion". A person who joined a mysterion was a mystes, meaning an initiate. These words are of uncertain etymology. Some historians have speculated that these words may be related to the Greek verb "myein", meaning "to close". This could be a reference to closed lips, implying secrecy, or it could refer to closing one's eyes and opening them to enlightenment.

Religion in the ancient Mediterranean was polytheistic, with people participating in rites honoring a multitude of gods. Collective religious activities, like festivals and temple rites, were a feature of public participation in civic life. Mystery cults had a more private nature, and their doctrines were often focused on the individual. Initiates took vows of secrecy upon entry into a mystery cult, which prevented outsiders from learning too much about its inner workings. The secrecy of these cults means that often little is known about their inner rites, doctrines and development.

Most mystery cults placed a heavy emphasis on personal salvation in their theological doctrines. This salvation could take the form of practical gifts like health, wealth, and safety, or spiritual gifts like a blissful afterlife. Some mystery cults became popular because it was believed that their deity was particularly responsive to prayers. In some mystery cults, this promise of salvation extended to the afterlife. These doctrines contrasted with the prevailing belief in a miserable afterlife for all except those who were deified in death.

Origins & Development

Historian Walter Burkert characterized the mystery cults as an "experimental" type of religion that drew from various pre-existing religious practices. The different mystery cults of antiquity did not all develop from a shared origin. Instead, they developed independently in regions such as Greece, Persia, Anatolia, and Egypt at different times and in different contexts. The practice of making vows to various gods in times of extremity, a basic aspect of ancient polytheistic religion, likely evolved into cultic initiations and rites based around vow-making.

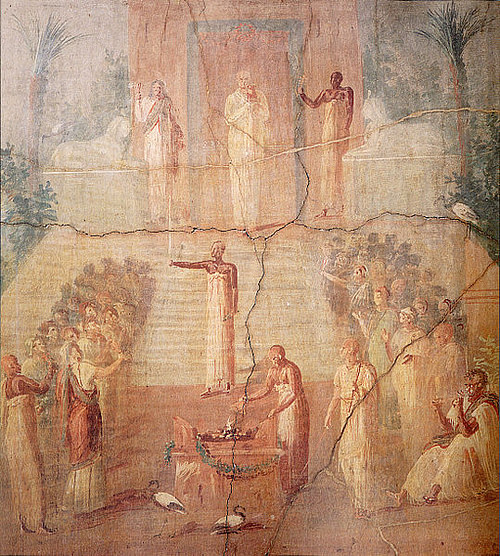

The earliest evidence for mystery cults comes from 6th-century BCE Greece. Some of these early mystery cults, such as the Eleusinian mysteries, may have originated in agrarian festivals related to planting and harvesting. The symbolism and mythological cycles of many mystery cults strongly relate to fertility and the agricultural cycle of harvest and rebirth. All of them involved the death of divine figures, which usually resulted in resurrection or rebirth in some form. These stories acted out the cycle of life and death that ancient people witnessed in the natural world. Through participation in their own symbolic rebirth, initiates hoped to share the power of that cycle.

Many mystery cults focused on mother goddesses and their consorts, such as the Roman Magna Mater (Cybele), the Egyptian cult of Isis, the Eleusinian mysteries (Demeter and her daughter Kore), and the Andanian mysteries. These cults tended to emphasize the fertile, life-giving aspects of these deities. Male figures associated with these cults often had feminine characteristics, such as the self-castrated god Attis or the often feminine god Dionysus. Some other cults, most notably the Roman cult of Mithras, were organized around masculine deities.

Cultic Rites & Initiation

Joining a mystery cult was a voluntary process, in which a person chose to undergo secret initiation rites in the hopes of attaining a higher level of spiritual awareness. Through this awareness, initiates hoped to achieve a closer relationship with a particular god. Initiation into mystery cults could take a variety of forms, but most required making some kind of vow and undergoing a sacred process. The Mithraic cult, which only permitted male members, required its initiates to undergo tests of courage and fortitude.

Unlike the official religions, in which a person was expected to show outward, public allegiance to the local gods of the polis or the state, the mysteries emphasized an inwardness and privacy of worship within closed groups. The person who chose to be initiated joined an association of people united in their quest for personal salvation.

(Meyer, 4)

Many cultic initiations involved the symbolic death and rebirth of participants. This was commonly represented by leaving initiates in darkness or blindfolding them and then ritually bringing them into the light as part of their rebirth into enlightenment. Many cultic initiations also involved a ritual meal of bread and wine. Once initiated into the cult, members often had to adhere to lifestyle changes, like the vegetarianism prescribed by the Orphic mysteries. Many cults also had specific attire for participants to wear during religious ceremonies, such as colorful parade clothing or simple linen clothing to represent purity.

Within the cult, there were different levels of initiation. Most members were probably motivated to join for social reasons, drawn by the appeal of belonging to a group. Some mystery cults could also convey a sense of prestige upon their members, and others were very egalitarian, allowing people from different social classes to interact as equals. In addition to secret rites, many cults also hosted public ceremonies such as feasts and processions during religious festivals. These occasions often included entertainment such as singing, dancing or theater. The processions of the Magna Mater and Isis were particularly famous for their size and spectacle.

Particularly devoted members hoped to gain spiritual enlightenment through their participation in sacred rites. Purifying rituals often included bathing or periods of fasting and sexual abstinence. As in all ancient Mediterranean religions, animal sacrifices and other offerings played an important role in worship. Those who could afford to might also commission shrines and other monuments to honor the cult's central deities.

Persecution

Mystery cults were often controversial in the ancient world on account of their secrecy and popularity. Some cults were also subversive of mainstream social mores, especially ones which permitted different social groups – like slaves and free people – to mingle freely. The Dionysian mysteries were frequently targeted both because its priestly leadership included men and women, and because its ceremonies were associated with wine drinking, ecstatic frenzy or ritual madness, and possibly sexual rites. This led to suspicion that the cult contributed to disorderly conduct, crime and immorality.

In ancient Rome, attitudes towards mystery cults of foreign origin were mixed. Some cults, like the Magna Mater, were readily assimilated into Roman culture as cornerstones of traditional religion. Others, like the Isiac cult, underwent cycles of tolerance and xenophobic persecution as social attitudes towards foreigners fluctuated. Rising intolerance towards foreign cults in the 1st century BCE did nothing to prevent them from becoming widespread, as citizens throughout the Roman Empire brought their gods with them.

Relationship to Christianity

In the early 20th century, many historians began to suggest that Christianity borrowed elements from mystery cults or that mystery cults competed with Christianity as emerging religions in Late Antiquity. Similarities between Christian rites and mystery cults were even noted by ancient authors, who speculated about a possible shared origin for them. Some Christian theologians, like Tertullian and Justin the Martyr, theorized that warped imitations of Christian rites had been introduced into mystery cults. Comparisons between Christianity and mystery cults are commonly made in modern pop historical treatments of religion.

However, most similarities are actually superficial and relate to the shared cultural context in which they developed. The consumption of sacramental bread and wine as spiritual nourishment in mysteries like the Mithraic cult has been compared to the Eucharist, but it can be better explained by the significance of bread and wine in the Mediterranean diet. Similarly, the shared emphasis on brotherhood, redemption, and resurrection reflects broadly applicable social concerns.

It is unlikely that the mystery cults directly influenced Christianity's theological development or popularity in the ancient Mediterranean. Historian Jan Bremmer noted that in some cases, the inspiration actually went in the opposite direction. For example, the spread of the Gospels resulted in the proliferation of similar resurrection narratives in pagan Roman literature.

The fact that initiation into the Mysteries could be a costly affair and that the Mithras cult was limited to males meant that pagan Mysteries were no competition for Christianity on the religious market, as the latter always received young and old, rich and poor, male and female into its fold. Moreover, unlike the Mysteries, Christianity was not esoteric but at first openly proclaimed its message, which was clear to all.

(Bremmer, 165)

Although Christianity's rise resulted in the disappearance of mystery cults, it is unlikely that a mystery cult could have taken Christianity's place. Unlike Christianity, these cults generally had a limited membership, and no mystery cult ever came close to being a dominant religion. Even the most egalitarian mystery cults did not approach the cross-societal appeal of Christianity. Additionally, Christianity was unique in that its adherents had to renounce all other gods and not participate in pagan rites.