Narmer (c. 3150 BCE) was the first king of Egypt who unified the country peacefully at the beginning of the First Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - 2613 BCE). He has also, however, been cited as the last king of the Predynastic Period (c. 6000 - 3150 BCE) before the rise of a king named Menes who unified the country through conquest. In the early days of Egyptology these kings were considered to be two different men. Narmer was thought to have attempted unification at the end of one period and Menes to have succeeded him, beginning the next era in Egyptian history.

This theory became increasingly problematic as time went by and little archaeological evidence supported Menes' existence while Narmer was well attested to in the archaeological record.The great Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (1853 - 1942 CE) claimed Narmer and Menes as the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty in that the two names designated one man: Narmer was his name and Menes an honorific.

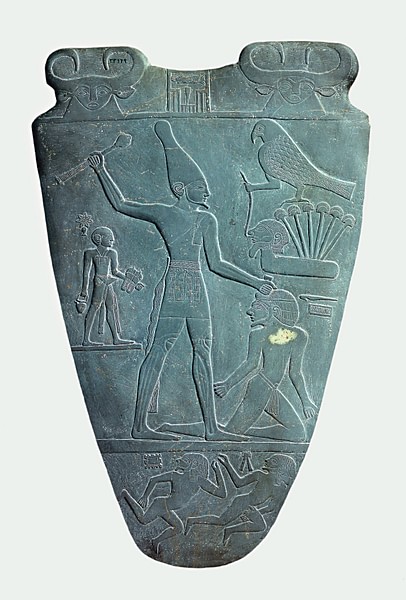

This same understanding holds for the other pharaoh associated with Menes, Hor-Aha (c. 3100 BCE), the second king of the First Dynasty who is also said to have united Egypt under central rule. If Hor-Aha was the ruler who achieved unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, then `Menes' was simply his honorific, meaning "he who endures". Some scholars claim there is no reason to argue over which of these kings may have united Egypt as the country wasn't truly united until the reign of Khasekhemwy (c. 2680 BCE), last king of the Second Dynasty and father of the king Djoser who began the Third Dynasty. This claim has been repeatedly challenged, however, since there is clear evidence of the king Den (c. 2990-2940 BCE) wearing the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, indicating unification under his reign. More significantly, the Narmer Palette (an ancient inscribed slab of siltstone) just as clearly shows Narmer wearing the war crown of Upper Egypt and the red wicker crown of Lower Egypt and so it is generally accepted that unification first took place under the reign of the king Narmer.

The Written Record & Unification

According to the chronology of Manetho (3rd century BCE), Menes was the first king of Egypt. He was a king of Upper Egypt possibly from the city of Thinis (or Hierkanopolis), who overcame the other city states around him and then went on to conquer Lower Egypt. This king's name is known primarily through written records such as Manetho's chronology and the Turin King List, (however it is not corroborated by any extensive archaeological evidence), which is why scholars now believe the first king may have been Narmer who peacefully united Upper and Lower Egypt at some point c. 3150 BCE. This claim of a peaceful unification is contested owing to the Narmer Palette which depicts a king, positively identified as Narmer, as a military figure conquering a region which is clearly Lower Egypt. Historian Marc Van de Mieroop comments on this:

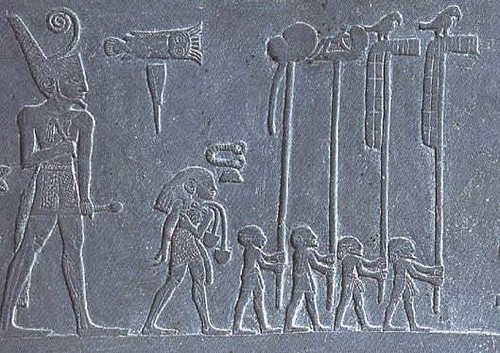

That Egypt was created through military means is a basic concept expressed in the art of the period. A sizeable set of stone objects, including cermonial mace-heads and palettes, contain scenes of war and fighting between men, between animals, and between men and animals.Whereas in the past Egyptologists read the scenes of war literally as records of actual events, today they prefer to see them as stereotypical statements of kingship and the king's legitimacy (33).

This new method of interpreting ancient inscriptions, however valuable some may consider it, does not mean such interpretations are accurate. The argument against such interpretations asks why, if these inscriptions are to be taken symbolically, others of later periods - such as those of Rameses the Great at the Battle of Kadesh - continue to be read literally as historical record. Van de Mieroop comments further, stating, "This new approach makes it impossible to date the unification of Egypt or attribute it to a specific individual on the basis of these representations" (33-34) but notes that, whatever the case regarding the first ruler, "the art of the period shows that the Egyptians linked unification with conflict" (34).

Scholar Douglas J. Brewer, on the other hand, does not see any problem in regarding the inscriptions symbolically. The name `Menes" means "He who endures" and, as noted above, could possibly be a title, not a personal name, in which case there is no difficulty in identifying the first king as Narmer 'who endured'. The name 'Menes' has also been found on an ivory inscription from Naqada associated with Hor-Aha, which could mean the title was passed down or that Hor-Aha was the first king. Brewer notes that these ancient inscriptions, such as the Narmer Palette, perpetuate "a culturally accepted scenario and, therefore, should perhaps be regarded as a monument commemorating an achieved state of unity rather than depicting the process of unification itself" (141). To scholars such as Brewer, the means by which unification came about are not as important as the fact of unification itself. The details of the event, like those of any nation's origins, may have been largely embellished upon by later writers. Brewer writes:

Menes probably never existed, at least as the individual responsible for all the attributed feats. Rather he is most likely a compilation of real-life individuals whose deeds were recorded through oral tradition and identified as the work of a single person, thereby creating a central hero figure for Egypt's unification. Like the personalities of the Bible, Menes was part fiction, part truth, and the years have masked the borderline, creating a legend of unification (142).

Unification, Brewer (and others) claim was "most likely a slow process stimulated by economic growth" (142). Upper Egypt seems to have been more prosperous and their wealth enabled them to systematically absorb the lands of lower Egypt over time as they found they needed more resources for their population and for trade. Whether the king who united the country was Narmer or someone of another name, this king lay the foundation for the rise of one of the greatest civilizations of the ancient world. Flinders Petrie, and others following him, claim that whether Narmer united Egypt by force is considered irrelevant in that it is almost certain he had to maintain the kingdom through military means and this would account for his depiction in inscriptions such as the Narmer Palette.

The Narmer Palette

The Narmer Palette (also known as Narmer's Victory Palette and the Great Hierakonpolis Palette) is an engraving, in the shape of a chevron shield, a little over two-feet (64 cm) tall, depicting Narmer conquering his enemies and uniting Upper and Lower Egypt. It features some of the earliest heiroglyphics found to date. The palette is carved of a single piece of siltstone, commonly used for ceremonial tablets in the First Dynastic Period of Egypt, and tells the story of Narmer's conquest c. 3150 BCE.

On one side, Narmer is depicted wearing the war crown of Upper Egypt and the red wicker crown of Lower Egypt which signifies that Lower Egypt fell to him in conquest. Beneath this scene is the largest engraving on the palette of two men entwining the serpentine necks of unknown beasts. These creatures have been interpreted as representing Upper and Lower Egypt but there is nothing in this section to justify that interpretation. No one has conclusively interpreted what this section means. At the bottom of this side of the palette, the king is depicted as a bull breaking through the walls of a city with his horns and trampling his enemies beneath his hooves.

The other side of the palette (considered the back side) is a single, cohesive image of Narmer with his war club about to strike down an enemy he holds by the hair. Beneath his feet are two other men either dead or attempting to escape his wrath. A bald servant stands behind the king holding his sandals while, in front of him and above his victim, the god Horus is depicted watching over his victory and blessing it by bringing him more enemy prisoners.

The top of the palette is engraved with bull's heads which some scholars interpret as the heads of cows. These scholars then interpret the cow heads to represent the goddess Hathor. It seems more sound to interpret the engravings as bull's heads, however, since a bull is featured prominently on the palette and would symbolize the king's strength and vitality.

Narmer's Palette

The Narmer Palette was discovered in 1897-1898 CE by the British archaeologists Quibell and Green in the Temple of Horus at Nekhen (Hierakonpolis), which was one of the early capitals of the First Dynasty of Egypt. As noted above, it was considered an account of an actual historical event until fairly recently when it has come to be regarded as a symbolic inscription. There are many different theories concerning the palette and each seems quite reasonable until one hears the next and so, to date, there is no consensus on what the inscription means or whether it relates to historical events. It seems clear, however, based on the age of the inscription and the images, that a great king named Narmer had something to do with the unification of Egypt and it is assumed that afterward he would have begun his reign.

Narmer's Reign of a United Egypt

Prior to Narmer's reign, Egypt was divided into the regions of Upper Egypt (the south) and Lower Egypt (the north, closer to the Mediterranean Sea). Upper Egypt was more urbanized with cities like Thinis, Hierakonpolis, and Naqda developing fairly rapidly. Lower Egypt was more rural (generally speaking) with rich agricultural fields stretching up from the Nile River. Both regions developed steadily over thousands of years throughout the Predynastic Period of Egypt until trade with other cultures and civilizations led to increased development of Upper Egypt who then conquered its neighbor most likely for grains or other agricultural crops to feed the growing population or to trade.

Once Narmer established himself as supreme king he married the princess Neithhotep of Naqada in an alliance to strengthen ties between the two cities. Neithhotep's tomb, discovered in the 19th century CE, was so elaborate as to suggest she was more than the king's wife and some scholars claim she may have ruled after Narmer's death. Her name, inscribed in serakhs from the time, supports this claim as do other inscriptions but it is still not universally accepted.

Religious practices and iconography developed during Narmer's reign and symbols such as the Djed (the four-tiered pillar representing stability) and the Ankh (symbol of life) appear more frequently at this time. He led military expeditions through lower Egypt to put down rebellions and expanded his territory into Canaan and Nubia. He initiated large building projects and under his rule urbanization increased.

The cities of Egypt never reached the magnitude of those in Mesopotamia perhaps owing to the Egyptians' recognition of the threats such development posed. Mesopotamian cities were largely abandoned due to overuse of the land and pollution of the water supply while Egyptian cities, such as Xois (to choose a random example), existed for millenia. Although later developments in urban development ensured the cities' continuation, the early efforts of kings like Narmer would have provided the model.

Details of his reign are vague owing to the lack of records discovered to date and, as noted above, the difficulty in interpreting those inscriptions which have been found and positively identified as relating to Narmer. As far as can be discerned, however, he was a good king who established a dynasty which would lay the foundation for all that Egypt would eventually become.

![Narmer Palette [Two Sides]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4412.jpg?v=1746123666-1721384182)