![Narmer Palette [Two Sides] (by Unknown Artist, Public Domain) Narmer Palette [Two Sides] (by Unknown Artist, Public Domain)](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4412.jpg?v=1763087296-1721384182)

The Narmer Palette (also known as Narmer's Victory Palette and the Great Hierakonpolis Palette) is an Egyptian ceremonial engraving, a little over two feet (64 cm) tall and shaped like a chevron shield, depicting the First Dynasty king Narmer conquering his enemies and uniting Upper and Lower Egypt. It features some of the earliest hieroglyphics found in Egypt and dates to c. 3200-3000 BCE. The palette is carved of a single piece of siltstone, commonly used for ceremonial tablets in the First Dynastic Period of Egypt. The fact that the palette is carved on both sides means that it was created for ceremonial instead of practical purposes. Palettes which were made for daily use were only decorated on one side. The Narmer Palette is intricately carved to tell the story of King Narmer's victory in battle and the approval of the gods at the unification of Egypt.

Background of the Palette's Scenes

The engraving depicts a victorious Egyptian king unifying the land under his rule. Traditionally, this king was known as Menes, the first king of the Early Dynastic Period who united Upper and Lower Egypt through conquest. His predecessor, according to the 3rd century BCE historian Manetho, was a king named Narmer, who sought to unify the country through peaceful means. Menes has been associated with Narmer and also with Menes' successor, Hor-Aha, who is also credited with the unification of Egypt.

Manetho's original chronology has been lost but is quoted extensively in the works of later writers. In the early days of Egyptology, Manetho's list (apart from the gods-as-kings which begin it) was taken as fact but, as more artifacts and temples were discovered, this view shifted. The claim of Menes as the first king of the First Dynasty grew increasingly hard to maintain as no archaeological record of such a king surfaced, and when the rare Menes artifact did come to light, it did not seem to designate explicitly the first king of the First Dynasty (which is why the name 'Menes' is associated with three different rulers).

Egyptologist Flinders Petrie was the first to associate Menes with Narmer and claim they were a single ruler. 'Menes', according to Flinders Petrie, was an honorary name meaning "he who endures" while Narmer was a personal name. The association of the name 'Menes' with the later ruler Hor-Aha would pose no problem in that Hor-Aha could have been given the same honorific when he was king.

Narmer, then, was the first king of the First Dynasty of Egypt and the Narmer Palette was most likely created to celebrate his military victories over Lower Egypt. The palette clearly indicates the king of Upper Egypt conquering Lower Egypt and thus unifying the two, but modern scholarship doubts this was actually accomplished by one king. Dates for the unification of Egypt run from as early as c. 3150 BCE to as late as c. 2680 BCE. It is usually accepted that the date for unification is c. 3150 BCE at the beginning of the First Dynasty but upheavals during the Second Dynasty (c. 2890-2670 BCE) indicate that this unification did not last. Every king of the Second Dynasty had to contend with some kind of civil unrest or outright civil war and inscriptions from the time indicate the conflict was between Upper and Lower Egypt, not foreign antagonists. If Narmer did unite the two lands of Egypt he most likely did so through military conquest and, if he united the lands peacefully, would have probably had to hold it together through repeated campaigns such as the one depicted on the Narmer Palette.

Description

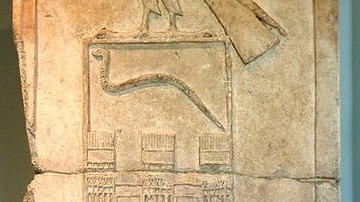

On one side, Narmer is depicted wearing the war crown of Upper Egypt and the red wicker crown of Lower Egypt which signifies that Lower Egypt fell to him in conquest. Beneath this scene is the largest engraving on the palette of two men entwining the serpentine necks of unknown beasts. These creatures have been interpreted as representing Upper and Lower Egypt but there is nothing in this section to justify that interpretation. No one has conclusively interpreted what this section means. At the bottom of this side of the palette, the king is depicted as a bull breaking through the walls of a city with his horns and trampling his enemies beneath his hooves.

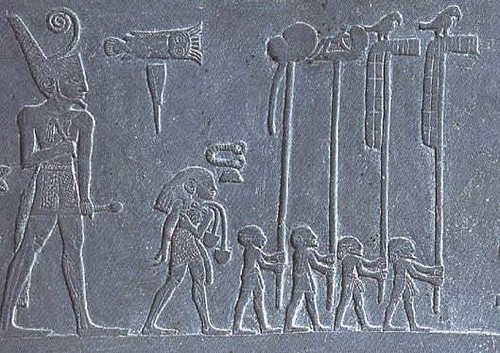

The other side of the palette (considered the back side) is a single, cohesive image of Narmer with his war club about to strike down an enemy he holds by the hair. Beneath his feet are two other men either dead or attempting to escape his wrath. A bald servant stands behind the king holding his sandals while, in front of him and above his victim, the god Horus is depicted watching over his victory and blessing it by bringing him more enemy prisoners.

Both sides of the palette are decorated at the top with animal heads which have been interpreted as either bulls or cows. Archaeologists and scholars who claim those are the heads of cows associate the engravings with the goddess Hathor, who is regularly depicted as a woman with a cow's head, a woman with cow's ears, or simply as a cow. As Hathor is not associated with warfare or conquest, this interpretation makes no sense in context. A more sensible interpretation is that the heads represent bulls since the king is depicted elsewhere on the palette as a bull storming a city. The bull would represent the king's strength, vitality, and power.

Discovery

The Narmer Palette was discovered in 1897-1898 CE by the British archaeologists Quibell and Green in the Temple of Horus at the city of Nekhen (also known as Hierakonpolis), which was one of the early capitals of the First Dynasty of Egypt. The scenes engraved on the siltstone were considered an account of an actual historical event until fairly recently when it has come to be regarded as a symbolic inscription. There are many different theories concerning the palette and, to date, there is no consensus on what the inscription means or whether it relates to historical events.

The palette was discovered among other artifacts associated with Narmer's reign such as his mace and another mace fragment inscribed with the name of King Scorpion. Scorpion may have been one of Narmer's predecessors or could have been an adversary and rival for the throne. Quibell and Green failed to note where the palette was found in relation to the other objects and further failed to include the location where many other artifacts were discovered in their survey.

The result of their mistake in proper recording is that no one knows what the relation of the artifacts were to each other and where they were discovered in the temple. If they were together in one area it could mean they were considered sacred objects or perhaps simply valuable artifacts stored in a safe place. If they were found separately, the precise spot in the temple could shed some light on how they were regarded. If King Scorpion's mace was located in a chest and Narmer's in a place of honor (or vice versa) much might be deduced on how these pieces were regarded by the people of the time. No such notes were made, unfortunately, and the artifacts were simply removed without cataloging them. Any interpretation of the pieces found in the 1897-1898 dig at Nekhen must be speculative.

Interpretation

This speculation extends to the Narmer Palette, which might depict an event from history or may simply be an honorary engraving which shows the strength and vigor of the king in battle. The evidence of civil conflict during the Second Dynasty, as noted above, indicates unification did not hold and that it was Khasekhemwy (c. 2680 BCE), last king of the Second Dynasty, who succeeded in unifying Egypt in the way Narmer is shown on the palette. Khasekhemwy has long been a strong candidate for the honor of the first king to unify the country and this claim is supported by the prosperous reign of his son, Djoser (c. 2670 BCE), who built the Step Pyramid and its surrounding complex at Saqqara.

It seems clear that Khasekhemwy did unite Egypt but evidence such as the Narmer Palette and inscriptions showing King Den (c. 2990 BCE) wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt strongly suggest Khasekhemwy was not the first. Egypt would experience a number of periods of civil strife and fracture during its long history and would be reunited and reformed over and over again. Narmer's first unification would have had to be maintained by the later kings and, according to both inscriptions and physical evidence, it was. Khasekhemwy would have been only one of a number of rulers who had to put Egypt back together again, not the first to unite the two lands. The Narmer Palette, however one interprets it, shows that unification was accomplished centuries before Khasekemwy by King Narmer.