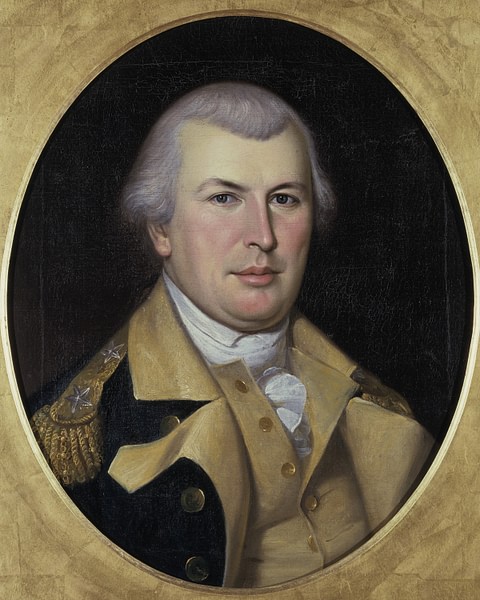

Nathanael Greene (1742-1786) was a general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). One of George Washington's most trusted subordinates, Greene served capably as Quartermaster General before leading the southern American army during the final years of the war. He is often considered the second-best American Revolutionary general, behind only Washington himself.

Early Life

Greene was born on 7 August 1742 on Forge Farm, near Potowomut Creek in the township of Warwick, Rhode Island. He was the third of eight sons born to Nathanael Greene Sr., a prosperous farmer and ardent Quaker; indeed, the father's piety must have been generational, as Greene's ancestors had initially fled England in 1635 to escape religious persecution. Nathanael Greene Sr., lived with his children and second wife, Mary Mott Greene (mother to the younger Nathanael), on the family farm, which had turned into a lucrative enterprise; by the time the younger Nathanael was born, the farm included a farmhouse, a general store, a gristmill, a sawmill, and a forge. The forge, which produced anchors and chains, was by far the most profitable aspect of the family business, employing many workers and eventually becoming one of the foremost businesses in Rhode Island.

As a child, the younger Nathanael had a thirst for education that could not be quenched by his father's strict Quakerism. As Greene would later recall:

My father was a man [of] great piety…[he] had an excellent understanding and was governed in his conduct by humanity and kind benevolence. But his mind was overshadowed with prejudices against literary accomplishments.

(quoted in McCullough, 21)

As a result of his father's 'prejudices', Nathanael and his brothers were not sent to school but were instead put to work in the fields. This did not stop Greene from seeking out knowledge on his own; under the guidance of Ezra Stiles, future president of Yale College, Greene became a voracious reader. Anytime he was not required to work in the fields or at the forge, Greene had his nose buried in a book, reading classical literature as well as the more recent philosophical works that defined the Age of Enlightenment. He was also fond of studying mathematics, history, and law.

The autodidactic Greene grew into a handsome, robust man nearly six feet (183 cm) tall, with strong arms, a broad forehead, and "fine blue eyes" (McCullough, 22). A childhood accident left him with a slight limp in his right leg, his right eye was cloudy as an effect of smallpox inoculation, and he often suffered from asthma attacks and poor health. Yet he was nevertheless a charismatic and jolly young man who was often found in the company of women. By 1770, Greene had proved industrious enough for his father to put him in charge of a second family-owned foundry in the town of Coventry, Rhode Island. When Nathanael Greene Sr., died later that same year, Greene and his brothers inherited the entire family business. In 1774, Greene courted and married the pretty 19-year-old Catherine 'Caty' Littlefield, with whom he would have seven children between 1776 and 1786.

The Fighting Quaker

After the death of his father, Greene worked to expand the collection of books in his library and began reading military treatises written by the likes of Frederick the Great and Maurice de Saxe. By this point, war with Great Britain was becoming a distinct possibility; the issue of 'taxation without representation' was just one of several policies pursued by the British Parliament that the Americans considered to be tyrannical, setting the Thirteen Colonies on a path toward confrontation with the mother country. Determined to turn himself into a 'fighting Quaker', Greene delved into the study of tactics and military theory and was soon one of the foremost military experts in Rhode Island (McCullough, 23). These studies, however, alienated him from the pacifist Quaker community. In July 1773, he was suspended from attending Quaker meetings after he had attended a military parade.

In 1774, Parliament passed the punitive Coercive Acts (known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts) in retaliation to the Boston Tea Party. The First Continental Congress, which met in Philadelphia in response to these acts, decided to place the county militias of the New England colonies on high alert, to prepare for a possible conflict with British soldiers. In October, Greene helped raise a militia unit, the Kentish Guards, but he was disqualified from serving as an officer because of his bad leg. Greene, who was notoriously sensitive about his limp, was determined to prove his fitness and joined the unit as a private. Armed with a musket he had purchased from a British deserter in Boston, he spent the next seven months marching and drilling with the other men, often outperforming them. Finally, in May 1775, Greene's colleagues recognized his talents and elected him brigadier general of militia, giving him command of three regiments of Rhode Island militia.

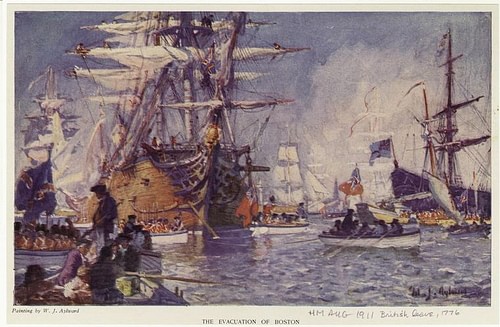

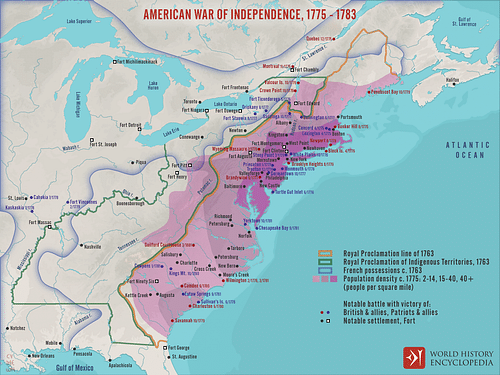

By this point, the first shots of the Revolutionary War had been fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775), and around 15,000 New England militiamen were laying siege to the British garrison in Boston, Massachusetts. Greene arrived at the Siege of Boston in early May, leading the 1,500 men of the so-called Rhode Island Observation Army. Although he was not present at the Battle of Bunker Hill (he was off visiting family in Rhode Island), his tireless work to maintain the siege quickly drew the attention of the Second Continental Congress. On 22 June, Greene was appointed to the rank of brigadier general in the newly formed Continental Army; at only 33, he was "the youngest of the first crop of brigadiers" (quoted in Boatner, 454). He also impressed the new commander-in-chief, General George Washington, who entrusted Greene with the command of a brigade of seven regiments. After the British finally evacuated Boston in March 1776, Greene briefly took command of the Continental garrison inside the city before leaving in April to rejoin Washington's army in Manhattan.

Serving Under Washington

Washington knew that the next large-scale British attack would likely be against New York City and that Long Island would be the key to its defense. In early May 1776, he put Greene in charge of fortifying Brooklyn, a task that the Rhode Island Quaker dove into with his characteristic energy. He rarely slept, supervising the work from horseback as his men constructed several fortifications along Brooklyn Heights, and scouting the terrain to familiarize himself with the potential battlefield. He even oversaw the construction of another major stronghold, Fort Washington, at the highest point of Manhattan, to guard access to the Hudson River; another fort, eventually named Fort Lee, was built on the New Jersey side of the river. Despite these efforts, which earned him the rank of major general, Greene became incapacitated by a severe illness and was therefore not in command when the British attack finally came at the Battle of Long Island (27 August).

The Continental Army was outflanked and defeated in the battle, losing over 2,000 casualties; ultimately, the Americans were forced to evacuate Long Island during the night of 29-30 August. Washington initially wanted to fortify New York City and make a stand there, but Greene and several other officers convinced him that the city was indefensible. On 15 September, therefore, the Continental Army abandoned New York City, leaving it to be occupied by the British forces. The next day, the Americans won a minor victory at the Battle of Harlem Heights – which was Greene's first taste of real combat – but were still heavily outnumbered and forced to retreat from Manhattan.

Greene was sent on ahead to take command of Fort Lee on the New Jersey side of the Hudson, a position he used to establish supply depots along a possible line of retreat. At the same time, Greene urged Washington not to evacuate the American garrison of Fort Washington in Manhattan, arguing that the fort could slow the British advance. This proved to be a dire mistake. On 16 November 1776, the British won the Battle of Fort Washington after only a few hours of fighting, capturing both the fortress itself and its 2,800-man garrison, a loss that the fledgling United States could not afford. The remnants of the Continental Army continued to retreat through New Jersey, evacuating Fort Lee mere hours before it, too, was captured by the British.

Greene was widely blamed for the losses of forts Washington and Lee, but General Washington still valued his abilities and resisted calls to remove him from command. As the Continental Army retreated toward the Delaware River, it relied on the supply depots that Greene had established. Still, disease and desertion reduced the army to barely 3,000 men by the time it reached the Delaware in December. Eager to redeem his reputation, Greene led one of the two American columns at the Battle of Trenton (26 December) and held a field command at the Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777). These two victories likely saved the Continental Army from destruction, allowing it to survive to fight another year.

Quartermaster General

In the following campaign season, Greene played an important part in the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777). When the British outflanked the right wing of the Continental Army, Greene's brigade held them off long enough to allow the rest of the army to retreat in an orderly fashion. Several weeks later, a mixture of fog and poor communication led Greene's detachment to arrive late to the Battle of Germantown (4 October), which resulted in another American defeat. On 19 December 1777, the Continental Army moved into winter quarters at Valley Forge, where it suffered from a dangerous lack of food and clothing; over 2,000 Continental soldiers would die that winter due to inadequate supplies.

With Congress' permission, Washington sought to reform the army's mismanaged supply department, but he needed someone he could trust to fill the position of Quartermaster General. In March 1778, Washington selected Greene for the role; although he felt that he was best suited for a field command, Greene reluctantly accepted the position. He immediately sent out foraging parties to scrounge up food for the starving army, while simultaneously working to reorganize the supply department. Before long, he established supply depots across the United States, improved the army's transportation system, and was keeping the soldiers supplied with food and clothing. Greene would hold the post of Quartermaster General for two years, performing his duties brilliantly. During this time, he continued to hold field commands and led troops at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778) and Battle of Rhode Island (29 August 1778) while also retaining his position on Washington's council of war.

Southern Campaign

By October 1780, the British army had launched their new 'southern strategy' and had won multiple victories in the American South; after winning the Siege of Savannah, Siege of Charleston, and Battle of Camden, they had overrun most of Georgia and South Carolina. Washington, who was busy defending the vital Hudson River Valley with the main army, was unable to go south himself. Instead, he appointed Greene to take command of the remnants of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. In December 1780, Greene arrived in Charlotte, North Carolina, to find an army of 1,400 men, many of whom were untrained, undisciplined, and undersupplied. With a British force under Lord Charles Cornwallis operating in South Carolina, Greene made the risky decision to split his army; Brigadier General Daniel Morgan would take the most experienced 600 men into South Carolina to support the Patriot militias operating in the region, while Greene himself remained in Charlotte to train the weaker half of his army and gather reinforcements.

Greene's gamble paid off the following month, when news reached him that Morgan had annihilated a British detachment at the Battle of Cowpens (17 January 1781). Morgan then raced back into North Carolina to link back up with Greene, with Lord Cornwallis and the southern British army in hot pursuit. In early February, Greene and Morgan decided to beat a northward retreat toward the Dan River on the border with Virginia, hoping to lure Cornwallis away from his supply centers in South Carolina. Greene's army easily outran Cornwallis, crossing the Dan on 14 February; Greene remained in Virginia long enough to bolster his numbers with Virginian militia before crossing back into North Carolina to challenge Cornwallis, who had established his headquarters at Hillsborough.

On 15 March 1781, Greene's army clashed with Cornwallis at the Battle of Guilford Court House near modern-day Greensboro, North Carolina. Greene adopted a defensive strategy similar to the one Morgan had used at Cowpens and split his army into three lines of defense; the first line consisted of North Carolina militia, the second line of Virginia militia, and the third line of experienced Continental soldiers. The advancing British soldiers were worn down by the first two lines of defense, which fired musket volleys before running off. The British army kept pushing, however, until they reached Greene's third defensive line, resulting in bloody hand-to-hand combat. The battle reached a stalemate until Cornwallis ordered rounds of grapeshot to be fired into the mass of soldiers, killing American and British troops alike. This swung the tide of battle in favor of the British, and Greene decided to order a retreat rather than risk the destruction of his army.

War of Posts

After his pyrrhic victory at Guilford Court House, Cornwallis marched his depleted army to Wilmington, North Carolina. Greene pursued but maintained a safe distance, as most of his militiamen had returned home. After licking his wounds, Cornwallis decided against finishing off Greene; instead, he opted to continue north and began marching for Yorktown, Virginia, in early April. Rather than give chase, Greene marched his own army south, spotting a golden opportunity to liberate South Carolina from the British soldiers Cornwallis had left behind. On 25 April 1781, Greene engaged a British detachment under Lord Francis Rawdon at the Battle of Hobkirk's Hill. Although casualties were roughly equal on both sides, Greene was ultimately beaten, a defeat that left him "almost frantic with vexation and disappointment" (quoted in Boatner, 1030). However, Greene refused to give up; he would later summarize the strategy of his southern campaign as "We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again" (ibid).

Greene's Fabian strategy would soon pay off. In May, most of Rawdon's army moved into Charleston, allowing the Americans free access to much of the South Carolinian countryside. In what Greene referred to as a 'war of posts', the Americans slowly began to wrest control of the state away from Britain by capturing the remaining British outposts. By the end of the summer, Greene was in control of the most significant of these outposts, including the fortress of Ninety-Six in South Carolina and the town of Augusta, Georgia; the British army had lost their foothold in the South, and now controlled only a sliver of coastal territory between Charleston and Savannah. On 8 September 1781, Greene fought the Battle of Eutaw Springs, which ended in an American retreat although the British troops took the brunt of the casualties. A little over a month later, news reached Greene that Cornwallis had surrendered to Washington after the Siege of Yorktown, bringing the active phase of the Revolutionary War to an end. Peace would be finalized two years later with the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

Later Life

Greene resigned his commission in August 1783 and returned to Newport, Rhode Island, where he was greeted as a hero and inducted into the local chapter of the Society of the Cincinnati. He had, by this point, accumulated a large amount of debt, as he had been forced to take out loans under his own name to keep his army supplied in the south. Although he was forced to sell much of his property in the north to help pay this debt, the state government of Georgia gifted him an estate outside Savannah as a show of gratitude for Greene's role in the state's liberation. Greene happily moved to his new plantation, Mulberry Grove, to begin his new life as a planter. It was not to be, however, as Greene soon died of sunstroke on 19 June 1786 at the age of 43. Today, Greene is often recognized as the second most important general of the Continental Army, behind only Washington himself. Multiple American towns and counties have been named in his honor.