The Native Peoples of North America (also known as American Indians, Native Americans, Indigenous Americans, and First Americans) are the original inhabitants of North America believed to have migrated into the region between 40,000-14,000 years ago, developing into separate nations with distinct and sophisticated cultures. These autonomous nations spread from Alaska, through Canada, and the lower United States.

The earliest periods of migration, settlement, and development are defined by archaeological evidence (spearheads, tools, monumental structures) from sites throughout North America and are most often referred to by the following terms:

- Paleoindian-Clovis Culture – c. 40,000 to c. 14,000 BCE

- Dalton-Folsom Culture – c. 8500-7900 BCE

- Archaic Period – c. 8000-1000 BCE

- Woodland Period – c. 500 BCE to c. 1100 CE

- Mississippian Culture – c. 1100-1540 CE

During the Archaic Period, some Native populations moved from a hunter-gatherer paradigm to a more sedentary social model as evidenced by sites such as Watson Brake (c. 3500 BCE), Poverty Point (c. 1700-1100 BCE), and others of varying size, developed throughout the region during the Woodland and Mississippian Culture eras. The cultures that developed in and around these sites were distinct from one another but shared a worldview that included belief in a higher power and disembodied spirits, the value of community over individual needs, reciprocity in interaction with the environment and each other, the importance of ritual and tradition, the practice of warfare and slavery, and conservation of resources. Women were highly respected in the communities and frequently served as leaders or advisers in government.

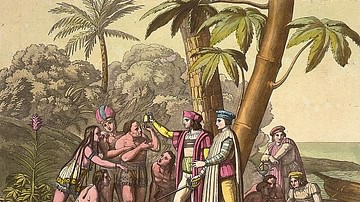

These separate communities developed into what are sometimes called 'tribes' (but more often referred to now as 'nations') at some point prior to c. 980 to c. 1030 CE when the first European settlement was established in North America by Leif Erikson at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. By the time of the beginning of European colonization of the Americas in the 15th century CE, they were highly developed political and social entities associated with a specific region and a certain territory within that region. Although European expansion across Canada and the United States eventually deprived the indigenous peoples of their ancient lands, the nations still exist today and the image of the 'vanished Indian' is as much of a myth as the 'noble savage' or similar tropes developed by European and American scholars during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Regions & Inhabitants

The first immigrants are believed to have arrived from Asia across the Bering Land Bridge (also known as Beringia) that connected modern-day Siberia with Alaska and are thought to have arrived with dogs, which were already domesticated. At the same time, or later, people are also believed to have arrived by sea, establishing themselves along the west coast and down through South America. Based on archaeological evidence, there seem to have been several migrations over many years, but why the people chose to relocate is unknown. From Beringia, the people moved into the region of modern-day Alaska, across Canada, and down through what is now the United States. By the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,000 BCE), migrants had established themselves as far south as modern New Mexico. As the earth warmed and the glaciers melted, Beringia was submerged c. 10,000 BCE, ending further migration across a land route, though it is possible people still arrived by sea.

All of the above is the generally accepted narrative of how North America came to be inhabited, but it should be noted these are only theories. No one actually knows how or when people first appeared on the continent, and each Native American nation has its own origin story.

However it happened, and wherever they came from, North Americans had established themselves in different regions by the Archaic Period, developing unique cultures and tribal identities eventually numbering over 500, with a population in the millions (a precise number is challenged and ranges between 6 -70 million or more). Owing to considerations of space, only a few of these tribal entities are listed below by region and language family.

- Arctic/Alaska – Eskimaleut - Aleut, Haida, Input, Inuit, Tlingit, among others

- Canada – Inuit, Metis, and over 50 distinct nations numbering over 600 diverse communities

- Northwest Coast – (roughly Alaska down to northern California) – Athabascan, Chimakum, Chinookian, Haida, Salishan, and Tlingit, numbering over 60 distinct tribal entities

- Northeastern Woodlands – (from the Great Lakes through the Ohio and Mississippi valleys) – Algonkian (Algonquin) and Iroquois nations, numbering over 50 distinct socio-political entities

- Southeastern Woodlands – (roughly the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee) – Muskogean, Yuchi, Siouan, and Iroquoian nations, numbering around 50 different tribes

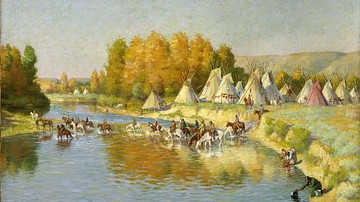

- Plains and Prairie – (from the Mississippi Valley to the Rocky Mountains and south to the Rio Grande, roughly) – Algonkian (Algonquin), Siouan, and Caddoan Nations, numbering around 40 different tribes

- Plateau – (roughly the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of lower Canada) – Lutuamian, Salishan, Shahaptian, and Waiilatpuan nations, numbering over 20 different tribes

- Great Basin – (roughly the states of Colorado, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, and part of Idaho) – the Uto-Aztecan nations including the Shoshone and Paiute, numbering around 10 tribes

- California – Hokan, Penutian, Ritwan, Uto-Aztecan, Yukian, numbering around 30 tribes

- Southwest – (roughly the states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and part of upper Mexico) – Athabascan, Pueblo, Tanoan, Uto-Aztecan, Yuman, and Zuni, numbering over 50 tribes

Community Development & Agriculture

These nations developed from the communities established during the Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian eras and, by c. 1540 CE, were sophisticated socio-political entities. Scholar Michael G. Johnson writes:

The complicated geographical diffusion of tribes with a common ancestral language base suggests continual movement, invasion, migration, and conquest long before the white man set foot on the continent. We know of substantial cultures that came and went long before European contact, such as the Adena and Hopewell cultures, which were partly based on Meso-American gardening. The Europeans did not, therefore, disturb a "Garden of Eden," but rather a continent of tribal groups and cultures that were fully dynamic. (8)

These cultures were already developing by the Dalton-Folsom period, which provides evidence of a belief in an afterlife, a spirit world, and a priority placed on the community above the individual. The Dalton-Folsom people developed technology for hunting and construction that included drills, hammers, scrapers, knives, and the atlatl – a stick with a cup at one end that held the butt of a spear and fired it toward an object with greater momentum than if thrown by hand.

During the Archaic Period (c. 2100 BCE), maize (corn) was introduced from Mesoamerican peoples trading with those of the North American southwest, encouraging the move away from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture and permanent settlements. Maize became the staple crop of the North Americans as its cultivation spread from the southwest in every direction. Beans and squash, also introduced from Mesoamerica, were joined with maize as the Three Sisters of agriculture – the corn stalks provide a natural trellis for the beans to climb, the beans process nitrogen for the roots of all three, and the squash leaves shade the ground, preventing weeds and regulating moisture. Nutritionally, the three crops also complement each other, providing a well-balanced diet.

Even after the cultivation of the Three Sisters became widespread, the hunter-gatherer culture continued with these crops serving as a supplement. Some nations – like those of the Great Plains – continued as hunter-gatherers longer than others. The peoples of the southeastern woodlands began erecting monumental sites c. 5400 BCE and developed the technology that produced major population centers such as Watson Brake, Poverty Point, Etowah Mounds, Serpent Mound, Pinson Mounds, Moundville, and Cahokia – once the largest urban center on the North American continent. These centers – except for those like Pinson Mounds or Serpent Mound, understood as religious/astronomical sites – engaged in local and long-distance trade with each other, establishing well-worn routes between the cities, acceptable forms of barter, and production/distribution methods.

Society, Spirituality, & Warfare

As noted, each of these nations were distinct cultural entities, and so any discussion of them as a group falls into generalities. Overall, Native American culture was informed by the spiritual beliefs of the people which held that all things were imbued with the same life force and deserved one's respect. Scholar Jack D. Forbes comments:

European writers long ago referred to indigenous Americans' ways as "animism," a term that means "life-ism." And it is true that most or perhaps all Native Americans see the entire universe as being alive – that is, as having movement and an ability to act. But more than that, indigenous Americans tend to see this living world as a fantastic and beautiful creation engendering extremely powerful feelings of gratitude and indebtedness, obliging us to behave as if we are related to one another. An overriding characteristic of Native North American religion is that of gratitude, a feeling of overwhelming love and thankfulness for the gifts of the Creator and the earth/universe. (2)

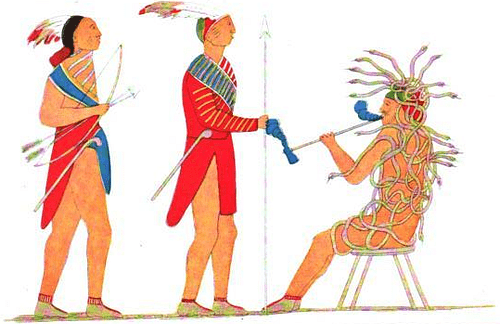

Each separate nation understood itself as part of every other, but this did not mean they always lived in peace or respected each other's territory. Wars were fought over water rights, to prevent outsiders from hunting in one's territory, for tribal prestige and power, and for captives who could be ransomed or held as slaves. Common weapons were the bow and arrow (first developed during the Woodland Period), spears, knives, and tomahawks. Some warriors also carried shields made of animal hide and wore breastplate armor of hide and animal bone. Scalps were taken from enemies killed in battle as trophies and encouraged personal prestige, respect, and social standing. Contrary to the view later perpetuated by European and American writers, Native American Nations mounted formal pitched battles, engaged in the exchange of prisoners of war, and entered into peace treaties with each other.

One's individual tribe was considered the most important and, as Johnson observes, "many [tribal] names translate simply as the 'real people' or 'original people'" in establishing their primacy though, as Johnson also notes, many of the tribal names known today are not the same as those the indigenous Americans knew in the past (8). One was responsible for honoring the beliefs of one's tribe and respecting the land of one's people but was not obligated to extend that same courtesy toward outsiders unless a formal agreement had been reached joining nations in a mutually beneficial pact. One of the reasons Native Americans first engaged in contact with European arrivals was for the advantage guns and horses gave them over their neighbors.

Wars were fought and lands and captives were taken out of a perceived necessity to sustain one's people, but there was no concept of 'land ownership' comparable to the European model. The earth and its resources did not belong to anyone specifically but were a gift of the Great Spirit to everyone collectively, and one was expected to give back through rituals of reciprocity that maintained the life cycle. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman describes one such ritual observed for ensuring robust harvests:

At the core of long-established Native American beliefs is one that the rhythms of the universe are like those of a steady drumbeat. In order to be renewed, the rhythms and cycles of nature require human participation in the form of rituals that mark important points in the cosmic cycle. Such Earth-renewal rituals are usually based upon the seasons, or crucial times in the food-supply calendar. These first-food ceremonies are profoundly important – celebrating fertility and marking the renewal of a subsistence cycle, which incorporates everything from the appearance of the first salmon or buffalo to the growth of corn. (230)

Generally speaking, all indigenous American groups held to this same basic belief although their forms of expression differed. Nations usually got along well with each other, engaged in trade, and allowed others to live peacefully except when conflicts arose.

Government, Daily Life & Inventions

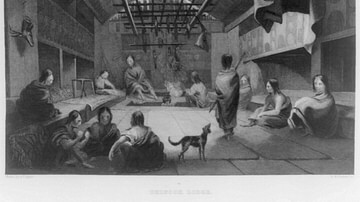

Women raised the children, built the homes, and cooked the food; men hunted for food and protected the village from outside threats. Men and women both tended crops and played a role in government. Individual families were part of a clan and that clan was part of a tribe/nation. The leader of the nation was recognized as the chief, who made decisions after holding council meetings with the head figures of the clans that made up the tribe. Some nations banded together, like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy or Iroquois League), consisting of five separate nations operating under a democratic government, which influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States in forming their own. The Powhatan Confederacy was made up of over 30 tribes, who paid tribute to the chief of the Powhatans and participated in common rituals but maintained significant autonomy.

Homes differed by region and the needs of the people. The hunter-gatherers of the Great Plains favored portable homes, the teepee, made of buffalo skin; the Inuit built igloos and large tents of animal hide; the Pueblos made their homes of sun-dried brick; the people of the northeastern woodlands lived in the longhouse made of bent saplings and woven reed mats. These homes, as noted, were usually built by women but were maintained by both women and men. The day began at sunrise, sometimes with a ritual welcoming the dawn and a meal prepared over open fires or ovens heated by hot stones from a fire. The typical diet consisted of vegetables, fish, meat, berries, and nuts.

Hunting parties were almost always male, although women participated by building the seasonal sites and cleaning the game as it was brought in. Women also made clothing from animal hides and fur, sometimes decorated with the feathers of birds, each of which held some symbolic significance. Girls were brought up by their mothers and aunts, learning the skills of maintaining the home and community, and boys were raised by their fathers and uncles to hunt, fish, fight, and protect the village or city. Girls usually married between the ages of 13-15 and boys between 15-20. These unions were usually arranged by the parents, though not always, and the bride commonly took up residence with her husband's family.

Music and storytelling – often combined – were the most common form of entertainment but also served religious and medical purposes. Stories chanted to the beat of drums were believed to drive evil spirits out of a sick person or encourage harvests or bring rain. These rituals also included dance or the reenactment of an ancient story. The shaman of the tribe (often referenced as the "medicine man" or "medicine woman") did not just rely on chanting or dancing to heal the sick but was an expert in herbal remedies. Native Americans invented 'aspirin' in the form of willow tree bark and its salicylic acid. They also developed anesthetics (using peyote and coca or datura) and the syringe.

The Native Americans were responsible for the invention or development of many other items, games, and practices known today. They were the first to cultivate and use tobacco, sunflower, pumpkins, and peanuts and invented the parka, kayak, and harpoon. Mathematics and astronomical observatories were also developed from the Archaic Period onwards, as were urban planning, road systems, and open-air theaters and temples. Ball games and board games were popular forms of entertainment, and the development of technology like the atlatl improved accuracy in hunting. Chewing gum, processing maple syrup, the bunk bed, the canoe, field and ice hockey, lacrosse, sunglasses, moccasins, tug-of-war, and even the water gun were first conceived of by the indigenous peoples of North America, not to mention the many other inventions and innovations they borrowed from those to the south.

Conclusion

When the Europeans began making first contact with the Native North Americans in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, their impact was almost universally detrimental. European diseases, against which the natives had no natural defense, killed thousands while the genocidal policies and wars of the 17th-19th centuries, as well as enslavement and deportation, decreased the population further, allowing for increased European claims to ancestral lands. In time, Native Americans came to be represented in the popular imagination wholly through a European lens, which purposefully misrepresented them, as noted by Johnson:

The Indian has been portrayed historically as vain, cruel to captives, a brave fighters but with no taste for pitched battle, and susceptible to alcohol with resultant brawls, family disruption, and inertia. Alternately, the Indian has more recently been eulogized as enjoying perfect harmony with Mother Earth or nature, as having a perfectly democratic and egalitarian social organization, as being eminently spiritual, and considerate of friend, stranger, young and old. In the past few years, the Indian has been portrayed as a model conservationist, taking only what he needed from the natural world…All these images – partial, unbalanced, or at best taken out of context – are highly misleading, and should be taken with a decent amount of skepticism. (8)

Among the most dangerous of these images is that of the 'vanishing Indian', encouraging the myth that serves as the title of the work ”All the Real Indians Died Off” and 20 Other Myths About Native Americans by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker. As Johnson (among others) notes, "there are probably more North American Indians or people of Indian descent alive today than in 1492" (8). The belief in the extinction of the indigenous peoples of North America is simply a convenient means of ignoring the unjust and failed policies of the United States government toward them. Recent activism, however, and, especially, the persistent recourse of Native American advocates to the US legal system, shows promise of winning justice for indigenous peoples, setting the historical record straight, and clearly establishing how the original inhabitants of North America have not gone anywhere.