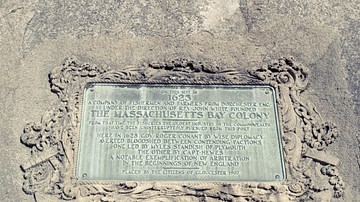

New English Canaan is a three-volume work of history, natural history, satire, and poetry by the lawyer and New England colonist Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE) published in 1637 CE. The book developed out of legal briefs Morton prepared for a lawsuit against the Massachusetts Bay Company and its settlement, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, to revoke their charter in New England and replace the existing government with one presided over by Sir Ferdinando Gorges (l. c. 1565-1647 CE), Morton's employer, who held the patent for the colonization of present-day Maine and part of Massachusetts.

The three volumes of New English Canaan, which present, respectively, the history, beliefs, and practices of the Native Americans, the landscape, wildlife, and fauna, and the poor treatment the New World was receiving at the hands of the Puritans and separatists, were initially written to support the lawsuit but, when that failed, were published to present Morton's case to the public at large. Printed in the Netherlands, which regularly published works considered seditious by the English government, 400 copies of the book were seized on publication and presumably destroyed. The few which made it into circulation were condemned by the Puritans and separatists, and Morton was arrested in Boston when he returned to North America in the 1640s CE.

The book and its author continued to be condemned and ridiculed up through the 19th century CE until American author Nathaniel Hawthorne (l. 1804-1864 CE) presented Morton's colony in a positive light in his short story The May-Pole of Merry Mount, published in 1832 CE. Later writers followed Hawthorne's lead in reevaluating Morton and his book, and today it is considered a classic of Colonial American history and literature. There are only 16 known copies of New English Canaan extant, held in museums and institutions mostly in the United States, and any other unknown copies at large are considered among the most valuable books in the antiquarian market.

Thomas Morton & Merrymount

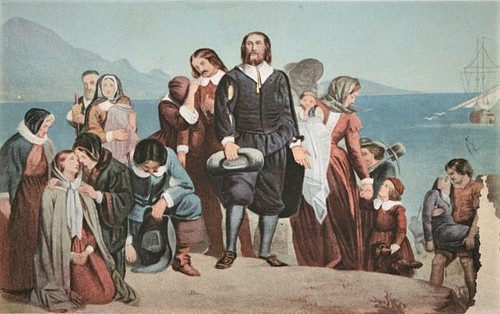

Thomas Morton was an English lawyer from Devon who had established a reputation for successfully representing lower-class clients in court cases when he was hired by Sir Ferdinando Gorges to handle his legal affairs in North American colonization. Gorges had invested in the short-lived Popham Colony established in Maine in 1607 CE but, when that failed, held back from further long-term commitments until 1622 CE when word arrived in England of the success of the Plymouth Colony, which had been founded in 1620 CE. Gorges applied for and received a patent to colonize the region of present-day Maine and sent Morton on a brief mission to the area in 1622 CE. The precise purpose of this trip is unclear, but in 1624 CE, Gorges sent him again on an expedition led by Captain Richard Wollaston (d. 1626 CE) with 30 indentured servants to launch a colony.

The fact that this group was able to legally establish the colony known as Mount Wollaston so close to Plymouth Colony makes clear that Gorges had legal rights to colonize that area. Plymouth Colony had been founded by accident in 1620 CE as they were originally supposed to have landed in Virginia but were blown off course to Massachusetts. They only received a legal charter to their settlement in 1622 CE and, even then, under the name of an investor, John Pearce, not under their own. Morton assumed control of the Wollaston colony in 1626 CE, renamed it Merrymount, and soon became Plymouth Colony's chief competitor in the fur trade.

Morton's view of the land, trade, and Native Americans differed significantly from that of the citizens of Plymouth Colony in that he viewed the natives as the equals or betters of the Christian colonists, regarded the land as abundant enough for everyone to share, and saw no reason to limit trade with the natives in any way. He established a communal settlement with no hierarchy (calling himself the colony's “host”, not their leader) where anyone was welcome, and all would share in the profits. Blending his own vision of Anglicanism with English paganism and Native American religion and spirituality, Morton created an ecumenical and interracial commune which, by 1627 CE, was financially successful and attracting others, both colonists and natives.

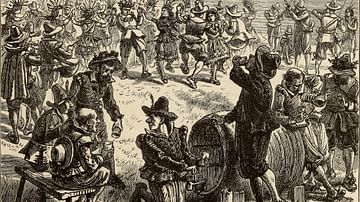

To the Puritan-separatist citizens of Plymouth Colony, however, Morton was no better than a devil, who engaged in and encouraged others to embrace “heathenish practices” in defiance of the Christian god and the scriptures. Morton did nothing to improve his image among his neighbors when, in 1627 CE, he erected an 80-foot high Maypole with antlers nailed to the top, which he and his people would dance around while drinking as often as they could.

According to the second governor of Plymouth Colony, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) in his Of Plymouth Plantation, two letters were sent by him to Morton demanding he stop trade with the natives – especially the sale of guns – and both were ignored. Finally, in 1628 CE, Bradford sent his militia's commander, Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE), to Merrymount who arrested Morton and imprisoned him on an island off the coast to starve to death. Morton was helped by Native Americans who provided him with food until he could return to England.

Morton came back in 1629 CE in the company of one of the Plymouth Colony's leading citizens, Isaac Allerton, Sr. (l. c. 1586-1659 CE) who had hired him as a clerk but he was shortly after arrested by the Puritan John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), future governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who also chopped down the Maypole and burned Merrymount. Morton was then sent back to England a second time.

The Lawsuit

Around 1630 CE, Morton began preparing the lawsuit which he hoped would revoke the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, turning its governance over to Gorges. The suit was a quo warranto, demanding that the government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony demonstrate by what authority they exercised their power. The colony had been given a Royal Charter in 1628/1629 CE but, as with Plymouth Colony, the application omitted the fact that the settlement was intended for Puritan colonization and focused solely on profits to be made for investors.

Morton argued that the charter should be revoked because the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony had not only misrepresented themselves in obtaining the charter but had no right to colonize the region in the first place as it was legally in Gorges' patent. The lawsuit dragged on between c. 1631-1635 CE with continuations proceeding on into 1641 CE. Morton eventually won, but it was a meaningless victory because the judgment could not be enforced.

Gorges had already managed to have himself named Governor of New England, even though he had never been to North America and never would, and had already established colonies in Maine which generated revenue so he no longer was interested in pursuing the matter. The English Civil War (1642-1651 CE) diverted whatever resources the crown might have put into enforcement but, even before this, when it looked as though the suit would fail, Morton decided to take his case to the public and publish the briefs which he had since turned into a three-volume history of early New England and an attack on his puritan and separatist enemies.

New English Canaan

It does not seem that Morton thought the book would in any way change the outcome of the lawsuit but, rather, that it would suggest to the public a new paradigm of colonization while making clear how inept and unfair the policies of the separatists at Plymouth Colony and the Puritans at Massachusetts Bay were. Scholar Peter C. Mancall comments:

Morton…understood that if the authority of the Massachusetts Bay Company disappeared, a replacement would need to be created. In some sense, this notion lay at the heart of New English Canaan. English readers needed to understand that this region could have a different future once the Pilgrims and Puritans lost their authority. (131)

This “different future” Morton suggests was a departure from the policies so far practiced by the separatists and Puritans by which they claimed lands belonging to the Native Americans, erected stockades around them, and invited more colonists who then required more land, all the while expecting the natives to be their grateful servants and assist them in trade. Morton offers his colony at Merrymount as the model for future possibilities where natives and colonists shared resources and engaged in equitable trade for both parties. In making his case, he describes the natives, the land, and how the rigid Puritan/separatist belief system was using both poorly.

The work is divided into three volumes:

- The history, beliefs, and practices of the Native American

- The land, wildlife, fauna, stones, and minerals of New England

- The history of the separatists and Puritans in New England 1620-1630 CE

In the first volume, Morton discusses a variety of topics concerning the Massachusetts tribe primarily as those were the natives he dealt with at Merrymount. He addresses, among other subjects, their religion, homes, clothing, natural intelligence, burial customs, and the ease with which they lived as contrasted with the English neighbors. In Book I, chapter 20, he writes:

I have observed that they will not be troubled with superfluous commodities. Such things as they find they are taught by necessity to make use of, they will make choice of, and seek to purchase with industry; so that in respect that their life is so void of care, they are so loving also that they make use of those things they enjoy (the wife only excepted) as common goods; and therein so compassionate that rather than one should starve through want, they would starve all. Thus do they pass away the time merrily, not regarding our pomp (which they see daily before their faces) but are better content with their own, which some men esteem so meanly of. (50)

Throughout his descriptions of the natives, he routinely adopts an admiring tone and makes no secret that he found Native American beliefs and practices far more humane than those of the English separatists and Puritans. At the same time, he could not completely reject his Anglican Christianity and repeats the claim that the natives essentially worshipped the devil, and that their shamans derived supernatural power from him, a number of times, as in this passage from Book I, chapter 9:

One amongst the rest did undertake to cure an Englishman of a swelling of his hand, for a parcel of biscuit. Which being delivered him, he took the party grieved into the woods aside from company and, with the help of the devil (as may be conjectured) quickly recovered him of that swelling and sent him about his work again. (30-31)

The second book is a natural history of the region addressing types of trees, herbs, birds, animals of the forests, stones and minerals, fish, streams, and waterways. Morton notes how all things grow and flourish in abundance and how hemp grows naturally and is superior to the hemp grown in England. He describes everything in detail and includes anecdotes concerning bears, moose, and fresh-water springs which were thought to have supernatural powers by the natives. In Book II, chapter 8, he describes one such spring:

Near Squanto's Chapel (a place so by us called) is a fountain that causeth a dead sleep for 48 hours to those that drink 24 ounces at a draught and so proportionably. The Savages that are powwows at set times use it and reveal strange things to the vulgar people by means of it. So that in the delicacy of waters, and the conveniency of them, Canaan came not near this country. (91)

The work relies consistently on allusions to classical Greek and Roman literature and the Bible in making its points and this is in keeping with its title. New English Canaan refers to the biblical account of the Hebrews, led by their general Joshua, taking the land of Canaan from the indigenous people and replacing them and their culture with their own. To Morton, the Puritans and separatists were abusing the natives and the land for profit and then justifying their actions in the name of their god and the scriptures.

He makes this point clearly throughout Book III, first by sharing episodes illustrating the inequitable and inept policies and practices of Plymouth Colony, then focusing on John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE, renamed Joshua Temperwell by Morton), the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and his arrival with over 700 settlers in 1630 CE. In Book III, chapter 23, he writes:

Seven ships set forth at once and altogether arrived in the Land of Canaan to take a full possession thereof. What, are all the 12 tribes of New Israel come?...And here comes their Joshua too among them and they make it a more miraculous thing for these seven ships to set forth together and arrive at New Canaan together than it was for the Israelites to go over Jordon dry-shod. (169)

Morton then briefly narrates the court which was convened to hear his case after Endicott had arrested him, concluding with his deportation and the burning of his home and colony. Morton references the natives who had been a part of the Merrymount community and their reaction to the verdict:

The harmless savages (his neighbors) came the while, grieved, poor, silly lambs, to see what they went about and did reprove these Elephants of Wit for their inhumane deed. The Lord above did open their mouths like Balaam's Ass, and made them speak in [my] behalf sentences of unexpected divinity, besides morality; and told them that God would not love them that burned this good man's house and plainly said that they who were new-come would find the want of such houses in the winter. (171)

The satiric elements of New English Canaan are most dramatic throughout Book III and include Morton's nicknames for various figures. Some of these are clearly identified, such as Winthrop or Myles Standish (called Captain Shrimp) while others are less clear. Mr. Innocence Fairecloath and Mr. Mathias Charterparty from chapter 25, for example, are not identified, though, like the others, they are understood to have been actual people. Fairecloath is used as an example of how the separatists pay their debts by coming up with excuses and, instead of paying what was owed, offer "an epistle full of zealous exhortations to provide for the soul and not to mind these transitory things that perished with the body" (177).

The last chapters of Book III deal directly with Puritan/separatist beliefs and how they direct policy, excluding anyone from justice under the law who is not a member of their faith. He concludes a comparison of the Anglicans with the Puritans/separatists in chapter 27 by pointing out how those outside the faith were treated differently than the Saints of the Puritan/separatist congregations:

They differ from us in the creed too, for, if they get the goods of one that is without [not of the faith] into their hands, he shall be kept without remedy for any satisfaction; and they believe that this is not cozenage [fraud]. And lastly, they differ from us in the manner of praying; for they wink when they pray, because they think themselves so perfect in the high way to Heaven that they can find it blindfold. So do not I. (188)

Conclusion

The book was seized by the English government upon publication, not because of its content, but because it had been published in Holland which was known for printing and disseminating anti-Anglican literature which was outlawed in England. It is likely the censors never even read the work. Morton sued for the return of 400 editions but never received a response.

New English Canaan did find an audience, however, and is considered the first book banned in what would later become the United States of America. Bradford criticizes it as a book of lies, but the later writer Samuel Maverick, in his A Brief Description of New England (published c. 1660 CE), notes how Morton was arrested at Boston and kept in jail "a whole winter, nothing laid to his charge but the writing of a book entitled New Canaan which, indeed, was the truest description of New England as then it was that ever I saw" (Dempsey, x). Other writers of the 17th and 18th centuries CE also comment on the work, mostly negatively, but some, like Maverick, defending it.

The largely negative view of Morton began to change in the 19th century CE after Nathaniel Hawthorne's work encouraged a reevaluation of him and his book. In the present day, although the work is still not as well-known as others of its time, it is considered of equal importance in its account of early Colonial America as it provides an alternate interpretation of events better known from the works of the Puritan/separatist settlers of New England who once banned it.