The Nihon Shoki ('Chronicle of Japan' and also known as the Nihongi) is an official history of Japan which was written by a committee of court scholars in 720 CE. It is a compilation of myths and legends concerning the Shinto gods and episodes from the reigns of the early emperors. The work begins with the story of the Creation and ends with the reign of Empress Jito in 697 CE. Drawing on older sources from Japan, China, and Korea, many of which are now lost, the text provides an invaluable insight into the mythology, customs, and politics of ancient Japan.

Background

The Nihon Shoki was a sequel of sorts to the Kojiki ('Record of Ancient Things'). Compiled in 712 CE by the court scholar Ono Yasumaro, the earlier work also described the mythology of the Shinto gods and the creation of the world. Not necessarily an accurate historical record, the Kojiki was principally commissioned to establish a clear line of descent from the ruling emperors of the 7th and 8th century CE back to the Shinto gods and the supreme sun goddess Amaterasu. The Nihon Shoki was designed to address some of the discrepancies in its predecessor and to reassert the genealogies of some of the clans (uji) neglected in the Kojiki, the latter work having greatly favoured the Yamato clan. The Nihon Shoki, therefore, repeats many of the myths of the Kojiki but often from a different view point and with changes in details. Like the earlier work, songs and poems are regularly inserted into the prose. The work, again like the Kojiki, drew on now lost texts (from Japan, China, and the kingdom of Baekje in Korea) and oral accounts making it an invaluable source of life in ancient Japan and its mythology.

One significant difference between the two works is that the later book has a much more polished prose and is much closer to contemporary Chinese histories in style. The Nihon Shoki presents multiple versions of the same myths and seems much more concerned with presenting a definitive historical presentation of events, even regularly citing the dates of events down to specific months and days. These differences have led some scholars to consider the Kojiki a work for national consumption while the Nihon Shoki was designed to show Japan's great history to the outside world, in particular in China and Korea, the two advanced cultures the Japanese court most wanted to appear favourably to.

The historian R.H.P. Mason describes the scope and significance of the Nihon Shoki as follows,

As an official history, the Nihon Shoki tends to concentrate on the role of the imperial line and its increasingly bureaucratic servants. Its two major themes, however, are sculpted even more grandly than this, and are of the utmost 'global' significance. They are, firstly, the slow coming together of the country under the hegemony of the Yamato Court; and secondly, the ever closer ties between that court and mainland states in Korea and China…the official record is anything but uneventful, and for the years after AD 550 it is essentially an account of how a few men finally transformed the loosely joined Yamato state into a centralized empire. (Mason, 38)

The Nihon Shoki was originally commissioned by Emperor Temmu (r. 672-686 CE) but finished by his son Prince Toneri in 720 CE, who edited the work of a group of court scholars. The book, written in Chinese, has 30 volumes covering the 'Age of the Gods' and Japan's creation in mythology, the early hero-like and legendary emperors, and then moves on to more historical emperors, ending with the reign of Empress Jito (686-696 CE). The earliest surviving copies of the Nihon Shoki date to the Nara Period (710-794 CE).

Extracts from the Nihon Shoki

On the creation of the first land:

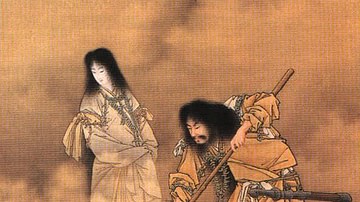

Izanagai no Mikoto and Izanami ni Mikoto stood on the floating bridge of Heaven, and held counsel together, saying: “Is there not a country beneath?” Thereupon they thrust down the jewel-spear of Heaven, and groping about therewith found the ocean. The brine dripped from the point of the spear coagulated and became an island which received the name of Ono-goro-jima. (Scott Littleton, 44)

On the death of Prince Shotoku:

The princes and the grandees, and, indeed, the entire populace of the realm grieved so greatly the streets were filled with the sounds of their lamentation; the old wept as over the death of a dear child, and the food in their mouths lost its savor, the young as if they had lost a beloved parent. The farmer cultivating his fields let fall his plow, and the woman pounding her rice laid down her pestle. They all said: - “The sun and moon have lost their brightness; Heaven and Earth must surely soon crumble - from this time forth, in whom shall we place our trust?” (Keene, 70)

On the policies of Emperor Temmu:

The Emperor issued an edict to the officials saying: “If any one knows of any means of benefitting the state or of increasing the welfare of the people, let him appear in Court and make a statement in person. If what he says is reasonable, his ideas will be adopted and embodied in regulations.” (Mason, 59)

On the talents of Prince Otsu, son of Temmu:

Imperial Prince Otsu was the third son of Emperor Temmu. His figure was outstanding and his words were clear, and Emperor Tenji loved him. When he was older, he had a gift for studying and especially loved calligraphy. The flourishing of poetry began with Otsu. (Scroll 30, nihonshoki.wikidot.com)

On the northern Emishi tribes:

I hear that the eastern outlanders are by nature fierce and wild, and that their chief interest is violent assault. Their villages lack chiefs, their settlements lack heads. coveting territory, they all rob each other. Further, there are evil deities in the mountains and perverse devils on the plains. They obstruct passage at intersections and block the roads, causing great affliction on people.

The fiercest of those eastern outlanders are the Emishi. Men and women live mixed together, nor is there distinction between father and son. In winter they lodge in holes; in summer they dwell in nests. They wear furs and drink blood; eldest and younger brothers are distrustful of each other…they have never since ancient times been subject to the transforming royal influence. (Whitney Hall, 29)

Empress Jito defines rules for the clothing of officials:

The colors of court clothes will be, from the rank Jodai-ichi down to Ko-ni, dark purple, from Jodai-san down to Ko-shi, reddish purple. The eight Jiki ranks will be red, the eight Kon ranks dark green, the eight Mu ranks light green, the eight Tsui ranks dark navy, and the eight Shin ranks light blue. Separately those above the rank of Joko-ni will have one strip of damask silk, and from Jodai-san down to Jikiko-shi two strips of damask silk, and they are approved for various uses. Also, all will wear a belt of fine, thin silk and white pants, regardless of status. (Scroll 30, nihonshoki.wikidot.com)

Legacy

Unlike the Kojiki, which inexplicably faded in popularity in the immediate centuries after its publication, the Nihon Shoki has always been given great importance in Japan. During the Heian Period (794-1185 CE) there were six separate series of lectures on the book sponsored by and delivered at the Japanese court. Right up to the 16th century CE the Nihon Shoki was considered the definitive and go-to source for Japanese history, and only in the last two centuries has the Kojiki overshadowed it, almost certainly due to the latter's less scholarly presentation and greater entertainment value.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.