Nisaba (also Naga, Se-Naga, Nissaba, Nidaba, and associated with Nanibgal) is the Sumerian goddess of writing, accounts, and scribe of the gods. Although her name is commonly given as Nidaba, noted scholar Jeremy Black points out that "the name Nisaba (or Nissaba) seems more correct than Nidaba" (Gods, 143).

She was originally a grain goddess worshiped at the city of Umma in the Early Dynastic Period I (2900-2800 BCE) but later became associated primarily with the city of Eresh (also Eres) whose location remains unknown. She was the daughter of Anu and Unas (personifications of Heaven and Earth), although, in certain cities like Lagash, she was represented as the daughter of Enlil and Ninlil, the divine couple who came to power with the blessing of Anu and Unas. In the best-known stories, however, Ninlil (also known as Sud) is Nisaba's daughter and Enlil her son-in-law, while Enki, god of wisdom, is her patron.

There is no known iconography for her as goddess of writing (although in her early form as a grain goddess she was represented as a single stalk), but there are many descriptions in written works. In the story Dream of Gudea she is pictured as "a woman holding a gold stylus and studying a clay tablet on which the starry heaven was depicted" (Kramer, 138). She became increasingly important throughout Mesopotamia, regularly invoked in blessings, supplications, even curses, and listed among the most prestigious deities in the Sumerian pantheon c. 2600-2550 BCE.

Nisaba developed in power and prestige along with the written word in Mesopotamia until she was known as the scribe of the gods and keeper of both divine and mortal accounts. Cylinder seals from the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) seem to depict her associated with construction, particularly of monuments and temples, which - along with her literary association - would link her to the Egyptian goddess Seshat.

Scholars are far from unanimous on this interpretation of the cylinder seals, however, because the symbol which might represent Nisaba on the seals is unclear. Her associations with Seshat are unmistakable, however, even if she were not identified with measurements in building projects.

As a grain goddess, she was linked to the god Ennugi (god of canals and dikes) as Nanibgal and was also known as Nun-barsegunu ('Lady Whose Body is the Flecked Barley'). Sanctuaries to Nisaba, with attached libraries and scribal houses, existed all across Mesopotamia from c. 2000 BCE to c. 1750 BCE. She is last attested to as associated with Eresh by Shulgi of Ur during the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE). During the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) her status declined, particularly during the reign of Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BCE) when goddesses lost prestige across Mesopotamia in favor of male deities. Nisaba was replaced by Nabu around this time when Hammurabi elevated Marduk to the position of king of the gods and Nabu as his son.

Nisaba & Writing

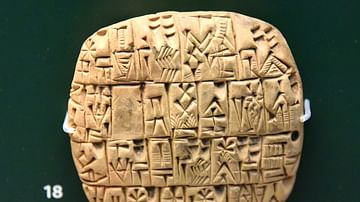

The Sumerians first invented writing c. 3500-3000 BCE as a means of long-distance communication in trade. With the rise of the cities in Mesopotamia and the increased need for certain resources each lacked, long-distance trade developed and with it the need to be able to communicate between regions. This early writing was known as cuneiform, impressions made with a sharp object in clay.

The earliest form of cuneiform was pictographs – symbols which represented objects – and served to aid in remembering such things as which parcels of grain had gone to which destination or the number of livestock sent to the temple. These pictographs were impressed onto wet clay which was then dried, and these became official records of commerce. With pictographs, one could tell how many sheep, vats of beer, or sheafs of grain were involved in a transaction but not necessarily what that transaction meant. The scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes:

All that had been devised thus far was a technique for noting down things, items and objects, not a writing system. A record of 'Two Sheep Temple God Inanna' tells us nothing about whether the sheep are being delivered to, or received from, the temple, whether they are carcasses, beasts on the hoof, or anything else about them. (63)

In order to express concepts more complex than financial transactions or lists of items, a more elaborate writing system was required, and this was developed in the Sumerian city of Uruk c. 3200 BCE. Pictographs, though still in use, gave way to phonograms – symbols which represented sounds – and those sounds were the spoken language of the people of Sumer. With phonograms, one could more easily convey precise meaning, and so, in the example of the two sheep and the temple of Inanna, one could now make clear whether the sheep were going to or coming from the temple, whether they were living or dead, and what role they played in the life of the temple.

Nisaba, formerly goddess of grain, became associated with writing as records were made regarding grain transactions. As the great lady who made the grain grow, she also oversaw the accounts of where it was distributed and how. Writing developed as trade grew until Nisaba was synonymous with the concept of writing and became known as "The Lady - in the place where she approaches there is writing" (Monaghan, 8). Cuneiform represented the spoken language of the Sumerians, but the form lent itself to other languages as well and was used by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and many others throughout the Near East. Scholar Betty Deshong Meador comments on this:

With the spread of writing from simple accounting to a multiplicity of uses - literature, communication, law, temple and palace records - the education of scribes became a necessity. Scribal schools, called E-DUB-A, "Tablet House", proliferated in cities and towns. The territory of Sumer boasted a formal school system by 2000 BCE. The schools trained students to read and to write cuneiform. Most were young men but evidence on ancient tablets reveals that women were scribes as well. The "signature" of the high priestess at Ur, Enheduanna, occurs on a number of hymns and poems that include her vivid descriptions of personal interactions with her goddess Inanna. Among the naditu cloister for women in Sippar, 600 years after Enheduanna, were scribes who served the business and personal needs of other women in the group. From the many tablets archaeologists uncovered, particularly in the religious capital of Nippur, scholars have been able to determine much of the sequence of the curriculum that the students followed in the scribal schools. For the first time in history, the orderly recording of acquired knowledge became a common practice. (cited in Monaghan, 8-9)

Nisaba became the goddess of literacy and patroness of the craft of writing. Scribal school tablets often end with the phrase, 'Praise be to Nisaba!' and Meador notes how "a young student wrote on one ancient tablet, 'I am the creation of Nisaba'" (Monaghan, 9). When she had been goddess of grains, she was represented in cuneiform as a grain stalk, which meant she was the grain itself.

Each early pictogram represented the thing itself, not concepts about an object or person, and so when the stalk of grain appears in early cuneiform the writer is saying Nisaba is present in that grain. In the same way, when she became goddess of writing, she was the written word; she was language; she was literacy; she was communication, learning; she was the writer and the written word.

Worship & the Rise of Nabu

Although Nisaba was worshiped at shrines and sanctuaries, no actual temple dedicated to her has yet been identified. She was honored at the temples of other gods such as those of Nabu and Ninlil, and these may have earlier been Nisaba's, which were later repurposed. Inscriptions make clear that her temple at Eresh was known as Esagin, 'House of Lapis Lazuli,' which was a center of worship for over 1,000 years.

Her worship eventually seems to have consisted primarily of the act of writing; in composing a written work, an author was honoring the goddess with the gifts she had given. She became synonymous with wisdom and learning and was invoked regularly by scribes, scholars, priests, astronomers, and mathematicians for inspiration and guidance in their work. Meador writes:

In Temple Hymn 42, Enheduanna calls her "faithful woman exceeding in wisdom." Already mentioned was her close relationship to scribes and scholarly activities. Mathematics and astronomy were in her repertoire. She was said to be "a lady with cunning intelligence." She was the goddess of creative inspiration, goddess of creative mind. (Monaghan, 11)

The famous Hymn to Nisaba, from the Ur II Period, is formally dedicated to her patron Enki, but opens with an invocation to the goddess:

Lady coloured like the stars of heaven, holding a lapis lazuli tablet! Nisaba, great wild cow born of Uras, wild sheep nourished on good milk among holy alkaline plants, opening the mouth for seven reeds! Perfectly endowed with fifty great divine powers, my lady, most powerful. (Black, Literature, 293)

The invocation is typical of the opening and closing lines of Sumerian compositions asking for Nisaba's help in creating the work and praising her for inspiration upon closing. This practice becomes less common, however, as Nabu takes her place during Hammurabi's reign.

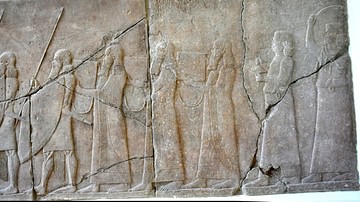

The Amorite king Hammurabi rose to power after his father, Sin-Muballit, was forced to abdicate in his favor. Once Hammurabi held the throne of Babylon, he steadily lay his plans for conquest and then acted on them, successfully defeating his enemies and creating an empire. He thanked his gods for these victories by elevating them in status at the expense of others, naturally, but Hammurabi's gods were predominantly male, and their prominence led to the loss of status of female deities throughout Mesopotamia; as well as a corresponding decline in the status and rights of women.

Strong, warlike, male deities (Marduk, Assur, Ninurta) became more popular than goddesses - even the very popular goddess Inanna, who was associated with war. Nabu, as Marduk's son, took Nisaba's place as the patron of writing and scribes, and she was relegated to a second-class role as his wife and consort. In this capacity, she kept the records and library of the gods but was no longer invoked for inspiration in creativity; this was now Nabu's role.

Still, she continued to be venerated at Nabu's temples for thousands of years. Nisaba is listed, along with Nabu, among the pantheon of the Neo-Assyrian gods c. 912-612 BCE. When the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, the gods most closely associated with Assyrian rule were targeted for vengeance by the invaders who destroyed their statues and temples. Some deities, like Nabu and Nisaba, were spared because, by that time, they had become assimilated by others or were remembered for their earlier Babylonian associations instead of Assyrian.

Worship of Nabu continued into the Christian era in Greece and Rome, while Nisaba remained confined to Mesopotamia for the most part. She was still being worshiped in the region during the Seleucid Period (312-63 BCE). After this time, her influence declines and she disappears, along with all the old gods, as Christianity gained wider acceptance.