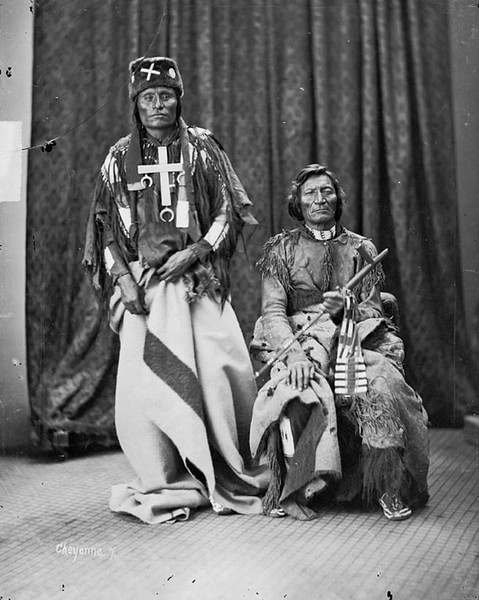

The Northern Cheyenne Exodus (1878-1879) is the modern-day term for the attempt by the Northern Cheyenne under chiefs Morning Star (Dull Knife, l. c. 1810-1883) and Little Wolf (also known as Little Coyote, l. c. 1820-1904) to leave the Southern Cheyenne Reservation in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) and return to their home in modern-day Montana.

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn (25-26 June 1876), in which the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho defeated the 7th Cavalry under Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876), Morning Star and Little Wolf gathered their forces to press for another Native American victory in the hopes of halting US westward expansion. They were defeated at the Battle on the Red Fork (also known as the Dull Knife Fight) on 25 November 1876.

The Cheyenne surrendered at Fort Robinson in modern-day Nebraska in 1877 with the understanding, based on the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, that they would be able to live with the Sioux in their ancestral homelands. Instead, they were forcibly deported to Indian Territory in the south where they found the conditions unbearable. In September 1878, Morning Star and Little Wolf led their people out of the reservation and headed north.

They were pursued by US authorities until they separated in October 1878, with Morning Star's band heading for the Red Cloud Agency to seek the protection of Chief Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909), and Little Wolf journeying toward the Powder River territory. Morning Star/Dull Knife's band was apprehended and taken to Fort Robinson where US authorities tried to starve them into submission and a return to the south. Little Wolf's band succeeded in reaching the Powder River. Later, the Northern Cheyenne were able to negotiate the establishment of what became the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana, where many of their descendants still live today.

Background

The westward expansion of the United States in the mid-19th century brought settlers into conflict with the Plains Indians and others who had been living on their lands for thousands of years. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was supposed to resolve these problems by clearly defining territories for each nation as well as those open for settlement by US citizens. This treaty was never honored, however, and was broken in 1858 when gold was discovered on Native American lands, leading to Pike's Peak Gold Rush.

Instead of honoring the treaty, the US government sent the military to protect US citizens who had no rights to the land they were mining and settling on. The First Sioux War (1854-1856), the Colorado War (1864-1865), and Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) were all Native American responses to the broken treaty and westward expansion. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 ended Red Cloud's War and was supposed to prevent further conflicts by establishing the Great Sioux Reservation, but this agreement was also never honored by the US government and was abandoned when Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills (on the Sioux Reservation) in 1874. This led to the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876, which the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho responded to in the Great Sioux War (1876-1877).

Custer and five divisions of the 7th Cavalry were wiped out at the Battle of the Little Bighorn by a coalition formed by the Sioux holy man and chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890) which included the Cheyenne and some Arapaho. Morning Star/Dull Knife did not participate in the battle, nor did Little Wolf (although he was on the field on 25 June). After the battle, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), Sioux war chief Gall (l. c. 1840-1894), and the other leaders dispersed, but, inspired by their victory, Morning Star/Dull Knife and Little Wolf mobilized Northern Cheyenne warriors to continue the fight. They were defeated at the Battle on the Red Fork (Dull Knife Fight) on 25 November 1876.

Indian Territory & Exodus

Morning Star/Dull Knife and Little Wolf surrendered to General George R. Crook (l. 1828-1890) at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska and were told they could stay there for a year, at least, while arrangements were made for a permanent home. Authorities in Washington, D.C., however, ordered Crook to send the Northern Cheyenne south to Indian Territory where the Southern Cheyenne were already living on a reservation. Crook and Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie (l. 1840-1889) promised the Cheyenne that, once they arrived at the reservation, if they did not like it after giving it a fair chance, they could return.

Morning Star/Dull Knife and Little Wolf refused, but Chief Standing Elk, who had greater influence, agreed to the terms and had his people mobilize to move south. 972 Northern Cheyenne left on the march, and only 937 reached their destination. Some of them slipped away from the column en route, and others died from exhaustion, disease, or exposure. They reached the Southern Cheyenne reservation in early August 1877. Scholar Dee Brown writes:

After a day or so, the Southern Cheyenne invited their northern relatives to a customary tribal feast for newcomers, and it was there that Little Wolf and Dull Knife first discovered that something was wrong. The feast consisted of little more than a pot of watery soup; this was all that the southerners had to offer. There was not enough to eat in this empty land – no wild game, no clear water to drink, and the agent did not have enough rations to feed them all. To make matters worse, the summer heat was unbearable, and the air was filled with mosquitoes and flying dust.

(334)

The Indian agent in charge, John D. Miles, encouraged the Northern Cheyenne to take up farming and promised more food would be coming while they planted their crops, but none came. Further, the arrival of 937 more people placed a strain on what food and supplies were available, and so the Southern Cheyenne quickly came to resent their presence and withheld food from the northerners. An outbreak of malaria was attributed to the newcomers, and the post surgeon quickly ran out of quinine to treat it, locked up his office, and left – as there was nothing he could do for anyone without medical supplies, which, though promised, never arrived.

Little Wolf told Miles that he was taking his people back north, as he had been promised he could do by Crook and Mackenzie, but Miles replied that was impossible unless word came from Washington, D.C., authorizing it. Little Wolf continued his attempts at negotiating a peaceful departure for the Northern Cheyenne, but Miles' responses were always the same. Finally, Little Wolf and Morning Star/Dull Knife decided they had to leave, authorization or not, and Little Wolf went to Miles one last time, telling him they were leaving and saying:

I do not want to see blood spilt about this agency. If you are going to send your soldiers after me, I wish that you would first let me get a little distance away from this agency. Then, if you want to fight, I will fight you, and we can make the ground bloody at that place.

(Brown, 340)

Miles did not believe the Northern Cheyenne were going anywhere but, to be sure, assigned a detachment to guard them and prevent any escape attempt. The soldiers, like Miles, did not believe the Northern Cheyenne would make any such move and so grew used to sleeping through the night watch. They woke up one morning to find the Northern Cheyenne gone. Warriors had been stealing horses for weeks and hiding them outside the reservation, and the entire band, now numbering around 350, had slipped away, mounted, and started off for their home in the north on 9 September 1878.

Battle of Turkey Springs & Kansas Raids

At 3:00 a.m. on 10 September, the alarm was raised, and, later, Captain Joseph Rendlebrock led a detachment in pursuit. Little Wolf and Morning Star/Dull Knife anticipated this and prepared an ambush at Turkey Springs. Both had fought in Red Cloud's War and used the same tactic Crazy Horse had at the Fetterman Fight in December 1866 of luring the soldiers into the ambush by sending out warriors in small bands to act as decoys.

Rendlebrock sent his two Arapaho scouts to negotiate, and while Morning Star/Dull Knife and Little Wolf kept them occupied, their warriors encircled the troops in the canyon. As soon as the parley was concluded and the Arapaho had returned to Rendlebrock with the news that the Cheyenne would not follow them back to the reservation, he ordered his troops to fire. As the Cheyenne had little ammunition, they chose their targets carefully, pinning the troops down on 13-14 September at what came to be known as the Battle of Turkey Springs. Rendlebrock finally ordered a retreat under fire from the Cheyenne, losing three soldiers and escaping with only three wounded.

The Cheyenne moved on into Kansas where Little Wolf sent out raiding parties to bring back food, supplies, weapons and ammunition, and horses. The raiding parties were instructed, as far as possible, to avoid killing anyone so as not to give the US authorities any further reason to pursue the Cheyenne. Even so, some people were killed, and the raiders returned with provisions, weapons, and horses. These raids were reported in the local papers, encouraging townspeople to join the army in hunting down the Cheyenne.

Lt. Colonel William H. Lewis led his troops and these volunteers, along with Arapaho scouts, to find and subdue the band, which was now being referred to as a dangerous group of renegades, and Little Wolf and Morning Star/Dull Knife prepared another ambush for them at Punished Woman's Fork, but this was spoiled when a young warrior fired on the Arapaho scouts in front of the column before it had fully entered the canyon. Still, the Cheyenne opened fire, mortally wounding Lewis. While the Cheyenne warriors were engaged with the cavalry in the canyon, a contingent of soldiers, circling around, discovered their horses and killed them. Once the Cheyenne withdrew, most had to travel on foot.

After a forced march of at least three days, the Cheyenne rested, and Little Wolf again sent out raiding parties. Although he and Morning Star/Dull Knife later said they had given the same command to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, many more White settlers were killed this time, property destroyed, and women and girls raped. The Cheyenne moved on into Nebraska, avoiding the pursuing troops as they pushed north.

Separate Paths & Fort Robinson Breakout

In October, Little Wolf and Morning Star/Dull Knife decided to separate. Morning Star was tired of running and wanted to head directly to the Red Cloud Agency, while Little Wolf preferred to winter in the Nebraska hills, out of sight of the cavalry, and resume the march in spring. Morning Star/Dull Knife was unaware that the Red Cloud Agency had been relocated to Dakota Territory and its previous place was now Fort Robinson.

On 23 October, Morning Star/Dull Knife's band was found by a contingent out of Fort Robinson and compelled to surrender. Prior to agreeing to follow the soldiers to Fort Robinson, however, the Cheyenne dismantled their guns, hiding the various pieces in their blankets or on their persons to seem as ornaments on clothing and moccasins or as charms and amulets. Fort Robinson could not easily accommodate the 150 new arrivals who were housed in the barracks.

The fort's commander, Captain Henry W. Wessells, wanted the Cheyenne gone as quickly as possible but recognized this would be difficult, with winter coming on. He sent word of his situation to Washington, D.C., and while waiting to hear back, he treated the Cheyenne well, ensuring they had enough food and blankets. By 3 January 1879, Wessells had received word that the Cheyenne were to be sent back to Indian Territory. Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) was brought in to help with negotiations, but Morning Star/Dull Knife refused to go back south. Wessells then locked the Cheyenne in the barracks, barred the windows, and stopped all provisions, including water and wood for the fireplaces.

On 9 January, the Cheyenne reassembled their weapons and tried to escape in the event now known as the Fort Robinson Breakout/Fort Robinson Massacre. Morning Star/Dull Knife and some others fled east, but many of the others were captured or killed. Captain Wessells found between 32-37 Cheyenne men, women, and children hiding in a dell on Antelope Creek and ordered his men to fire and keep firing until they were all dead, although twelve of them survived, some dying later from their wounds. The casualties were buried in a mass grave, which came to be known as "The Pit."

Morning Star/Dull Knife and his small band finally reached the Red Cloud Agency where they were taken under care and hidden from authorities. Little Wolf, after the two bands had separated, wintered in the Sand Hills, as he had planned, and then began the journey north when they were found by Lt. William P. Clark, who was sympathetic to the Cheyenne and talked them into surrendering.

Conclusion

Morning Star/Dull Knife stood firm in his resolve never to return to Indian Territory, and after reports of the Fort Robinson Massacre were picked up by newspapers, public opinion swung in support of the Northern Cheyenne. Morning Star/Dull Knife was able to negotiate the establishment of the Tongue River Agency in the Montana territory, now known as the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. He never lived to see it formally recognized in 1884, however, dying of natural causes in 1883.

Little Wolf, and many of his warriors, signed up to scout for the US Army and spent most of his time drinking until he died, also of natural causes, in 1904. He is buried near Morning Star/Dull Knife in the Lame Deer Cemetery on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

The decisions of US governmental authorities that led to the Northern Cheyenne Exodus and the Fort Robinson Massacre were typical of the policies enacted toward the Plains Indians in the 19th century. There was no real reason to send the Northern Cheyenne south in the first place, and once they had agreed to go, there was no reason why the authorities could not honor the promise made by Crook and Mackenzie that, if they did not like Indian Territory, they could return home.

The Northern Cheyenne were not asking for anything more than what had been promised them in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and by the two officers of the United States Army, and yet they were treated like fugitives once they left Oklahoma and were pursued over 700 miles (1125 km) in their attempt to return to the lands they had always known. Professor and author Joe Starita comments:

It's one of the deepest, most profound instincts that the human race has, to go home. That's what they wanted to do.

(Williams, 3)

Today, the Northern Cheyenne Exodus is remembered and commemorated by the descendants of those who made the journey from Oklahoma to Montana and survived. The event is dramatized in the 1964 John Ford film Cheyenne Autumn, based on the book by Mari Sandoz, and the history of the exodus was traced in many others. The story of the Northern Cheyenne in 1878-1879 mirrors that of many other Native peoples of North America whose homelands were taken by the United States in pursuing their vision of Manifest Destiny, progress, and civilization. The genocidal policies of the United States ultimately failed, however, as the Cheyenne survived and continue to observe their cultural practices and traditions in the present day.