The Northern or Baltic Crusades were military campaigns organised by popes and western rulers to convert pagans to Christianity in the 12th to 15th century. Unlike in the Holy Land, where military campaigns were aimed at liberating former Christian lands from Muslim rule, the crusades in Prussia, Livonia (modern Estonia) and Lithuania were aimed at converting the local pagan population.

The order of Teutonic Knights dominated the campaigns of the Northern Crusades from the mid-13th century and carved out its own militarised state in Prussia. Although the order did eventually convert the region to Christianity, the religious motive was essentially an excuse to acquire land and riches. The 15th century saw new challenges in the region from the Poles, Russians, and Ottoman Turks, and so the Baltic Crusades, having achieved their goal, were replaced by secular warfare.

Expanding the Crusade Ideal

Another arena for the crusades, besides the traditional campaigns to capture Jerusalem and other Middle East cities from Muslim control from the late 11th century onwards, was the Baltic and those areas bordering German territories which continued to be pagan. As with the Crusades in the Levant, rulers seized the opportunity to combine the religious benefits of crusading - crusaders had their sins remitted - with the thirst for territorial expansion and material wealth in the form of land, furs, amber, and slaves. In addition, the Northern Crusades, first conducted by Saxons and directed against the pagan Wends (western Slavs), provided a new facet to the Crusader movement: active conversion of non-Christians as opposed to liberating territory held by infidels.

The German Empire had a long tradition of sending Christian missionaries to states on its north-eastern frontier, a hotspot of many wars against the pagan states of eastern Europe. Adding fuel to the cause, atrocities against Christians and the murder of missionaries in these territories had been reported by such figures as the archbishop of Magdeburg in 1108. When the Second Crusade (1149-1147) was called by Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-1153) in December 1145 in order to recapture Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia, many German nobles preferred, instead, to first sort out the infidels in their own backyard rather than march off to fight those in the Levant. An assembly in Frankfurt in March 1147 decided that the Baltic would be the priority, and the decision was given a seal of approval by the influential abbot Bernard of Clairvaux. In April, Pope Eugenius III officially declared that such a crusade would, like that in the Middle East, earn its combatants a remission of sins. The Pope then went a step further with the following infamous statement of intolerance:

We utterly forbid that for any reason whatsoever a truce should be made with these tribes, either for the sake of money, or for the sake of tribute, until such time as, by God's help, they shall be either converted or wiped out. (quoted in Phillips, 89)

The Crusader movement was now an armed missionary campaign, and Eugenius even made the remission of sins benefit entirely dependent on pagans being successfully converted to Christianity. The starkness of the Pope's statement may reflect the traditional difficulty in converting the region, especially the Wends. There had been many instances of a profession of faith being later rescinded (considered a worse offence than being an infidel), of pagan practices carrying on anyway or even being mixed in with Christian ones, and of campaigns being abandoned in favour of temporary monetary gains. This new Crusade was designed to be the last in the Baltic.

The Wends Crusade

Before the Crusader army even set off, an additional motivator was provided by the Wends themselves who, realising trouble was around the corner, launched a pre-emptive strike on the Christian-held port of Lubeck. Between June and September of 1147, a Saxon-Danish army then attacked the pagan settlements of Dobin and Malchow, both in modern northeast Germany. Dobin got off the lightest when its population agreed to be baptised, so ending the fighting. Malchow fared rather worse, its temple with pagan idols was burnt down and the surrounding territories destroyed. After a failed siege at Demmin on the River Peene, the next target was Stettin on the River Oder in Pomerania, but the people there managed to persuade the Crusaders to hold off an attack by showing crucifixes from the city's walls. The overall campaign, despite its lofty aim and papal backing, fared little better than the usual annual raiding parties sent into the area. Neither was the Crusade helped by the divisive mistrust between the Danes and Saxons. The paltry net result was the conversion of one chieftain and the acquisition of booty while the Wends leader Prince Niklot remained in power and, despite the promises, his subjects continued as practising pagans. It was certainly not what Eugenius had envisaged.

Teutonic Knights: Prussia & the Baltic

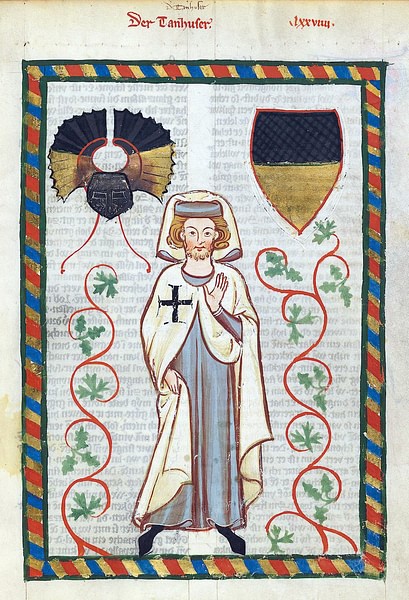

The Baltic would continue to be an arena for Crusades in the following centuries, especially with the arrival of the military order of Teutonic Knights from the 13th century. Between 1193 and 1230 Saxon Crusader armies were sent to defend Christian missions in Livonia, although once again it was more a case of a land grab than a religious mission and, despite military successes, long-term conversion or subjugation of the natives was not achieved. The Teutonic Knights would continue this work, absorb such local military orders as the Swordbrothers (in 1237) and fight an essentially non-stop campaign in Prussia from 1245 to the 15th century, continuously attacking the neighbouring Lithuanians and the Livonians further north.

The Teutonic Knights were a formidable fighting force of professional knights and infantry. Their heavy cavalry backed by a disciplined corps of crossbowmen capable of firing devastating mass salvos swept all before them. The knights were also far more adept at siege warfare than the peoples they faced, and they were master diplomats able to form handy alliances for mutual benefit against traditional enemies. There were frequent guerrilla attacks and regular localised revolts, including one major one in 1260, but the order was helped by an influx of Crusaders from other western and central European states, including some star names like Rudolf of Habsburg, Otto III of Brandenburg and King Ottokar II of Bohemia. Once more, the backing of the Pope proved essential, and the crusader ideal of defending Christianity was usefully transformed into one of conversion and taking the lands of those who did not accept the faith. The Teutonic Order's success in Prussia, which they essentially made into a state of their own (the Ordensstaat), was evident in its gradual transformation into a wholly German territory which institutionalised both war and religion; indeed, the region, at least for outsiders, came to epitomise German culture more than any other in later centuries.

Although military campaigns (reisen) were largely restricted to the winter season when marshes and lakes were frozen, the Teutonic order was hugely successful in gaining new territory, notably Danzig and eastern Pomerania in 1308 and northern Estonia in 1346, bought from the Danish king Valdemar IV (r. 1340-1375). New lands, mostly ports and along rivers, were then settled with migrant Germans, churches and monasteries were built (especially by the Cistercians), and the acquisitions defended via the construction of castles as part of a systematic colonisation. Lithuania was attacked with success, the cause there ending when the grand prince Jogailo (aka Jogaila) promised in 1386 to convert his pagan people to Christianity, a process formally completed in 1389.

By the end of the 14th century, lacking political unity and behind the west in terms of technology, much of the Baltic had been forcibly converted to Christianity. Thereafter, it became clear that the Teutonic Knights were mostly interested in politics, land, and booty, rather than conversion as the wars continued and pushed into Livonia. Indeed, the Teutonic Knights were frequently accused of slaughtering Christians, trashing secular churches, impeding conversions, and trading with heathens. It was said that many pagans in central Europe resisted Christianization only because they did not want to live under the brutal regime of the Teutonic Knights. The Teutonic Order was not alone in their ambitions in the region as Danish and Swedish kings used the same ideological cloak to invade northern Estonia and Finland in the 13th and 14th century.

Decline of the Teutonic Order

In the 15th century, when the Lithuanians and Poles joined forces with the Russians and Mongols, along with several other smaller allied states, the Teutonic order was threatened with extinction. At the First Battle of Tannenberg, 15 July 1410, an army of Teutonic Knights was wiped out, and in 1457 the headquarters of a now much-reduced and largely secular order had to be relocated to Konigsberg. The Teutonic order still continued at its Livonian branch into the 16th century and now primarily focused on battling, without much success, Orthodox Russians and Ottoman Turks. When the order was fully secularized in 1525 (Prussian branch) and 1562 (Livonian branch), crusading in the Baltic was over.