The Northwest Ordinance was enacted by the Confederation Congress of the United States on 13 July 1787. It created the Northwest Territory – comprised of the modern-day states of Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota – and laid out the procedure whereby new states could be admitted into the Union.

The Northwest Ordinance was enacted as a way to organize the settlement of lands west of the Appalachian Mountains and, ultimately, add new states to the Union. Previous land ordinances in 1784 and 1785 had gotten the original states to relinquish their claims to these western territories and had allowed Congress to sell off the land, but these ordinances had failed to mention how the territories were to be governed prior to achieving statehood. To solve this issue, Congress enacted the Northwest Ordinance, which mandated that the Northwest Territory – and all other incorporated territories of the United States – would initially be administered by a federally appointed governor who was empowered to appoint civil servants and make legislation. Once the population of the territory reached 5,000, it would be able to create its own representative assembly and, upon reaching a population of 60,000, could apply for statehood. According to the Northwest Ordinance, all new states admitted to the Union would have the same rights and privileges as the original thirteen states.

The Northwest Ordinance had a profound effect on the development of early US history. Most significantly, the Ordinance prohibited the expansion of slavery into the Northwest Territory; this effectively led to the geographic divide between 'free states' and 'slave states', helping to lay the groundwork for the national debate over the expansion of slavery that would lead to the American Civil War (1861-1865). A more immediate consequence of the Ordinance was that it brought the US government into conflict with the Native American nations who also laid claim to the territory, resulting in the Northwest Indian War (1790-1795). Additionally, the fact that the Northwest Territory was administered by a federally-appointed governor helped to enhance the authority of the federal government at a time when this was one of the most contentious political issues. Finally, the method of admitting new states to the Union laid out in the Ordinance would become the standard protocol for the entry of future states.

Land Ordinance of 1784

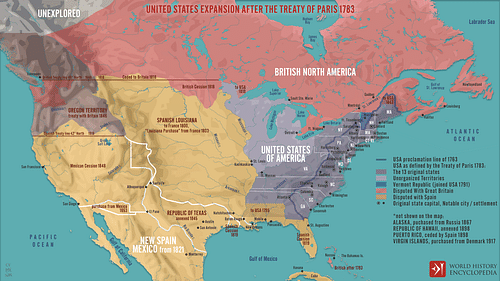

At the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, Great Britain ceded control of much of its lands west of the Appalachian Mountains to the United States, more than doubling the territory of the young republic. While this was a welcome surprise to many Americans, it also came with a set of problems – almost all this land remained undeveloped by Europeans and was home to around 100,000 Native Americans who were unlikely to welcome an influx of White settlers onto their lands. Furthermore, there was contention about who should govern this new western territory. Virginia had long laid claim to the lands along the Ohio River, citing its 1607 colonial charter, which proclaimed that Virginia's western border extended all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Other states – notably New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts – also had old, and often contradictory, claims on the western territories.

The ink on the Treaty of Paris of 1783 was barely dry, therefore, before the states began quarreling amongst themselves about who should control the lands in the West. Several smaller states, particularly Rhode Island and Maryland, strongly protested Virginia's claims – Virginia was already the most populous and most politically influential state, and the smaller states did not wish to see its power expand any further. New York and Massachusetts, whose charters had also granted them territorial rights 'from sea to sea' also battled over western lands that stretched to the Mississippi River. As the states squabbled over governance, the West was becoming lawless; land speculators and squatters who had flooded into the territory were coming into conflict with the Native Americans who lived there, while a lack of a defined legal process for settling these lands resulted in a myriad of feuds and legal battles that proved a headache for everyone involved. It was clear that a system for the governance and settlement of the western territories would have to be resolved, and quickly.

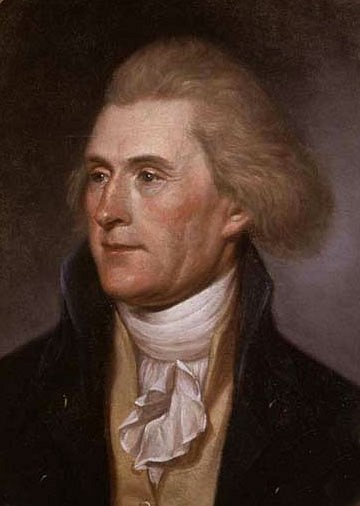

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson, then a congressional delegate from Virginia, offered a solution, proposing that every state should relinquish its western claims and that new states would instead be carved out from the territory. In return for giving up their claims on the West, Jefferson promised the states that the money gained from the sale of western lands would go toward the betterment of all the United States. The states begrudgingly agreed and, one by one, ceded most of their western claims to Congress (Virginia continued to lay claim to Kentucky until 1789). Jefferson immediately went to work drafting what would become the Land Ordinance of 1784. In Jefferson's plan, the western frontier would be divided into several self-governing districts, and the gate would be open to new settlers. Once any given district reached a population of 20,000, it could send a representative to Congress; once that same district reached a population equal to the least populous state, it could apply for statehood.

Jefferson envisaged ten new states arising from the territory, each with artificial, rectangular boundaries, and with names like 'Sylvania', 'Cherronesus', 'Illinoia', 'Metropotamia', and 'Washington'. Jefferson had also drawn up a list of guarantees that he wanted each district to agree to before it could govern itself. These included a guarantee to forever remain a part of the United States; to remain subject to Congress and help pay off Revolutionary War debts; to always maintain a republican government; and to ban slavery after the year 1800. Congress removed this last guarantee from the final draft and struck off Jefferson's plan for state boundaries but passed the rest of his Land Ordinance on 23 April 1784. For the first time, a rough plan for the admission of new states into the Union was in place.

Land Ordinance of 1785

Despite the adoption of the Ordinance of 1784, it was widely acknowledged that the ordinance had its issues. The most glaring problem was that Jefferson's ordinance failed to go into specifics about how the western districts would be governed or settled prior to achieving statehood. A congressional committee on western lands was set up to address this issue, consisting of Jefferson, Hugh Williamson of North Carolina, David Howell of Rhode Island, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, and Jacob Read of South Carolina. After some discussion, the committee decided to send out land surveyors to divide the territory into townships 'six miles square, by lines running north and south'. Each township was to be further divided into 36 sections of 640 acres each. Land would be sold to prospective settlers at auction; although a minimum price was set at one dollar per acre, no one could buy less than a section of 640 acres. Congress kept four sections in each township for future sale and set aside another section for the purpose of public education.

This plan was adopted by Congress on 20 May 1785 as the Land Ordinance of 1785; the policy of land surveying it laid out eventually became the basis of the Public Land Survey System. The land surveys began immediately, under the direction of Captain Thomas Hutchins, Geographer of the United States. Within the next few months, seven townships had been surveyed along the southeastern part of the Ohio River; United States troops were sent both to protect the surveyors from Native American attack and to drive out White settlers who were squatting on the land illegally. Congress hoped that, by keeping the price for land relatively high, they would keep out poor and unrefined settlers who were more likely to start conflicts with Native Americans. Instead, Congress hoped to attract well-off, educated farmers who would make the most of the untouched farmland on the frontier, bring Western civilization to the region, and – hopefully – treat their new Native American neighbors with more tact.

Western Settlement

After several months passed, it became apparent that the sale of lands to enterprising individuals would not go as smoothly as Congress had hoped, as few were actually buying the land. In desperation, Congress turned to Eastern land speculators who were hoping to turn a profit from the land. In 1787, Congress made a deal with the Ohio Associates, a joint-stock land company made up of former Continental Army officers. Congress sold 1,500,000 acres of western land to the Ohio Associates for $1 million. This sale encouraged other private companies to begin buying up western lands including the Connecticut Land Company, which bought up 3,000,000 acres in the vicinity of modern-day Cleveland, Ohio.

These land speculators tried to resell the land to prospective settlers at lower prices than Congress had initially offered, but their luck was little better than Congress' had been. Settlers continued to stream into the western lands, but they turned their noses up at the speculators who tried to sell to them; with the lack of organized authority in the region, why bother purchasing land when they could find lands to settle on for free? One Ohio settler, foreshadowing the later concept of Manifest Destiny, put it this way:

All mankind…have an undoubted right to pass into every vacant country, and there to form their constitution, and that…Congress is not empowered to forbid them, neither is Congress empowered…to make any sale of the uninhabited lands to pay the public debt.

(Wood, 120)

Congress tried to stop the flood of illegal settlers by sending soldiers back into the Ohio Country to burn the squatters' settlements; however, the squatters simply fled into the woods when the soldiers arrived and rebuilt their homes once the soldiers had gone. Most of the squatters did not even live in one place but moved around, frustrating Congress' ambitions of establishing permanent western settlements while at the same time worsening tensions with the local Native Americans by constantly violating the terms of previously established treaties by moving onto their lands. Meanwhile, most of the land speculation companies, facing imminent financial trouble, were forced to give much of their purchased land back to Congress. By 1787, it was apparent that yet another land ordinance would be needed to clean up the mess that was quickly growing in the West.

Northwest Ordinance of 1787

In 1787, as delegates from the states were meeting at the Constitutional Convention to replace the ineffectual Articles of Confederation, Congress discussed a new land ordinance. What it produced on 13 July 1787 – the Northwest Ordinance – would widely be considered the crowning legislative achievement of the short-lived Confederation Congress. First and foremost, the ordinance proclaimed that all new states admitted into the Union would enjoy “equal footing with the original States, in all respects whatsoever” (Wood, 122). The ordinance established that Congress – not state governments or private companies – would be the only authority in control of territories of the United States, which helped to enhance the power of the federal government. The ordinance also organized the lands in question into the nation's first organized, incorporated territory, known as the Northwest Territory.

The Northwest Ordinance improved on Jefferson's original 1784 legislation; the Northwest Territory would be divided into five states, not ten, and a more detailed method was devised for territories to become states. Each new western settlement was to be initially governed by a federally appointed governor, a secretary, and three federal judges. The governor would serve a three-year term and be responsible for creating and leading the local militia, appointing local magistrates, and drafting laws. Not until the territory's population reached 5,000 would it become eligible to form a representative assembly, and even then, the governor would wield the most power; the governor could veto legislation or dissolve the representative assembly at will. Once the territory's population reached 60,000, it could apply for statehood and, if granted, would be allowed all the same rights, liberties, and privileges of other states. The near-authoritarian power of these territorial governors was deemed appropriate to bring order to the West and prevent unnecessary conflicts with Native Americans.

Aside from establishing a new method for the admittance of states, the Northwest Ordinance also listed a series of natural rights for the US residents of the territory including religious tolerance, public education, as well as protection of legal and property rights – this coming four years before the Bill of Rights was added to the United States Constitution in 1791. Significantly, Congress also declared that slavery and indentured servitude were prohibited in the Northwest Territory; this was a major victory for abolitionists, who sought to snuff out the institution of slavery by preventing its expansion. The origin of the conflict between 'free states' and 'slave states' that would ultimately lead to the American Civil War can therefore be traced to the Northwest Ordinance. The six states that were eventually formed from the Northwest Territory all continued to prohibit slavery after they had been granted statehood.

Aftermath

The protocol for admitting new states into the Union, as put forth by the Northwest Ordinance, stuck. In 1789, the new federal government under the US Constitution renewed these provisions in the Northwest Ordinance of 1789. At a time when the most contentious political issue was the power of the federal government, the Northwest Ordinance proved an invaluable victory for the Federalists, who supported increased federal power; by way of the federally appointed governors, all incorporated US territories would be directly administered by the federal government, thereby increasing its authority. However, the increased interest of the US government in the Northwest Territory, as well as waves of new settlers to the region, naturally led to conflict with the Native American nations who also claimed the territory. The resultant Northwest Indian War took up much of the attention of the Washington Administration, although it eventually ended in a US victory.

Thanks to the Northwest Ordinance, six new states were eventually carved out of the Northwest Territory and admitted to the Union: Ohio (admitted in 1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837), Wisconsin (1848), and Minnesota (1858). The prohibition of slavery in these territories helped set the geographical line that divided 'free' and 'slave' states at the Mason-Dixon Line in the Missouri Compromise of 1821. The issue of slavery would continue to be a contentious issue as new states continued to be added to the Union, culminating in the American Civil War.