The Nuremberg Rally, or the Reich Party Congress, was an annual event held from 1927 to 1938 in Nürnberg, Germany. Organised on a massive scale by the National Socialist Party (Nazi), these operations in pomp, ceremony, and propaganda were attended by hundreds of thousands of party members. The climax was always a speech by the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945).

The Power of Propaganda

The National Socialist Party rallies were first held in Nuremberg in Bavaria in 1927 and continued until the outbreak of the Second World War (1939-45). Previously, Nazi rallies had been held in Munich and Weimar, but Nuremberg allowed the Nazis to play on its rich history, since in medieval times, the city had been the diet of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The Nazis even began to call Nuremberg "the most German of German cities" (Range, 115). The city also had the advantage of a large open space for mass gatherings, the Luitpoldhain park.

These annual events, held each September and attended by Nazi party members, spanned several days. Unlike other gatherings of other political parties, Nuremberg was designed from the start as a place for show and spectacle, not the usual motions and debates on the intricacies of party policy. Hitler wanted unity and decreed that the rallies were to be a "clear and understandable demonstration of the will and the youthful strength" of the National Socialist Party (Range, 149). This was, however, still a period when the Nazi party was battling for electoral recognition, and it was not until 1933, when the Nazis took power, that the Nuremberg rallies became truly grandiose affairs.

The Nazis understood the power of presentation and the positive effects of well-orchestrated pomp and ceremony on a populace that perhaps had yet to be fully convinced of Nazi policies and their wild ambitions for Germany. Hitler had devoted two chapters of his book Mein Kampf (published in 1925) to the subject of propaganda, in particular, the power of imagery and slogans on the masses. Hitler and his master of propaganda Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945), who took on this role in 1928, were constantly on the lookout for opportunities where the people could be impressed by sights, sounds, and words. As Hugh Greene, a British journalist based in Berlin in the late 1930s noted:

Showmanship was very important to the Nazis. I think that Hitler quite consciously wanted to keep the German people, or the mass of them, in a state of constant intoxication. The annual event at Nuremberg was of particular importance. (Holmes, 38)

People came to Nuremberg on special trains and stayed in military barracks, empty warehouses, tents, and railway carriages. Special guests were invited for their prestige, such as Prince August Wilhelm (1887-1949), the son of Kaiser Wilhelm II (r. 1888-1918), and Winifred Wagner (1897-1990), daughter-in-law of the composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and organiser of the important Bayreuth music festival. Sympathetic foreigners, particularly diplomats and journalists, were also invited to the rallies so that they could report back home favourably on Hitler and Nazi Germany.

Designing the Zeppelin Field

The Nuremberg rallies were carefully planned, orchestrated, and dressed to achieve the desired degree of intoxication and, above all, instil a sense of belonging. As Goebbels once remarked, attendance at a rally transformed the participant "from a little worm into part of a large dragon" (Hite, 254). The first important element was the place itself, but the Nuremberg site needed expanding. "A whole district of Nuremberg was set aside for the rally-complex, which was planned (and to some extent built) on gigantic lines" (Stone, 77). A theatre of dreams (or was it nightmares) was to be constructed, a massive stadium on a large open space that became known as the Zeppelin Field.

To build and dress this gigantic set, Hitler called upon Albert Speer (1905-1981), the man who would fast become his favourite architect. Speer reshaped Nuremberg in the summer of 1933 so that it was suitable for hosting what was now the party in power. Speer described one of his early design features as follows: "I provided a gigantic eagle, over a hundred feet in wingspread, to crown the Zeppelin Field. I spiked it to a timber framework like a butterfly in a collection" (Speer, 62). In 1934, Speer was commissioned to enlarge the Zeppelin Field structures and, for the first time, build them in stone (pink and white granite). Speer described his approach to this most important of projects:

I struggled over those first sketches until in an inspired moment, the idea came to me; a mighty flight of stairs topped and enclosed by a long colonnade, flanked on both ends by stone abutments. Undoubtedly it was influenced by the Pergamum altar…With some trepidation I asked Hitler to look at the model. I was worried because the design went far beyond the scope of my assignment. The structure had a length of thirteen hundred feet and a height of eighty feet. It was almost twice the length of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome.

(Speer, 96)

Hitler agreed to the plan. The completed stadium had a capacity for hundreds of thousands of spectators. Many party members would be so far from the stage that they needed special glasses to be able to see what was happening, but that was incidental; the point was that the stadium and the crowd looked terrific on film. Above all, the structure was permanent. Both Hitler and Speer had an eye on history, and this influenced the choice of design and materials, as the architect here explains:

Hitler liked to say that the purpose of his building was to transmit his time and its spirit to posterity. Ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture…By using special materials and by applying certain principles of statics, we should be able to build structures which even in a state of decay, after hundreds or (such were our reckonings) thousands of years would more or less resemble Roman models…To illustrate my ideas I had a romantic drawing prepared. It showed what the reviewing stand on the Zeppelin Field would look like after generations of neglect, overgrown with ivy, its columns fallen, the walls crumbling here and there, but the outlines still clearly recognizable.

(Speer, 97)

Speer achieved his dream for his design since the structure still sits today, as planned, a seemingly indestructible ruin. Other permanent buildings added by Speer to the Nuremberg complex included a huge hall for cultural events. The massive plans, which won a prize at the 1937 World Fair in Paris, were never completed in full. The entire rally complex was to have covered 16.5 square kilometres (6.5 sq. mi), but the war intervened in its final execution.

Another feature of Speer's Nuremberg was the use of the Nazi flag, a striking arrangement that repeated itself in huge banners throughout the stadium area and through the streets of Nuremberg. The flag had a deliberate and particular significance, as here summarised by the historian F. McDonough:

The Nazi flag with its distinctive and visually memorable Swastika logo – designed by Hitler – was a potent symbol of party identity. It was basically red, borrowing that colour from the popular communist red flag, but in its centre was a white circle – to represent the pure Aryan heritage – with the visually memorable black Swastika symbol, borrowed from earlier Volkisch sects, in the centre. The flag ingeniously incorporated the red of socialism with the traditional black and white of the pre-1914 imperial flag.

(72)

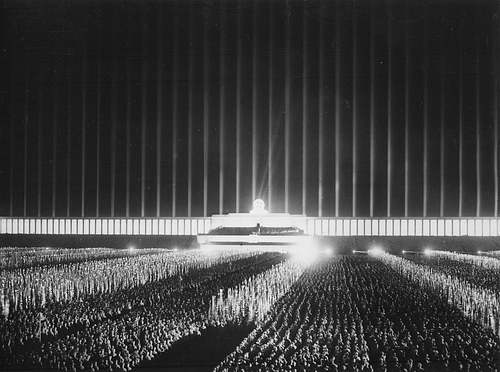

The next thing was to get the lighting right since the most important parades were held at night. Speer suggests in his memoirs that he decided on night parades only to disguise the poor marching abilities and even poorer physiques of the thousands of aged party members who were to participate, but he then realised the dramatic potential of powerful lighting. Speer designed the lighting system at Nuremberg to accentuate the architecture and make his Führer seem god-like. Lights with powerful beams, including 130 aircraft searchlights, were set all around and above the stadium, shooting their beams 20,000 feet (6 km) into the air. Spotlights could be directed at a particular point or moved quickly around to create blinding light shows. One pro-Nazi press report gives the following description of the luminary pyrotechnics used at the 1936 Nuremberg rally:

As Adolf Hitler is entering the Zeppelin Field, 150 floodlights of the air force blaze up. They are distributed around the entire square, and cut into the night, erecting a canopy of light in the midst of darkness…The wide field resembles a a powerful Gothic cathedral made of light…A devotional hour of the Movement is being held here…The men's arms are being lifted in salute…the applause that rises from the 150,000 spectators…lasts for minutes.

(Hite, 254)

Pomp & Ceremony

The rallies always opened with a performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg by the Berlin State Opera. There then followed four days of marches, parades, speeches, music, and fireworks. There were ceremonies of significance to the history of the party such as the parade when district party flags were individually touched to the corner of the bloodied flag that had been used in the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed Nazi coup d'etat of 1923. The rally's grande finale was always the same: Hitler's speech. For this climax, the spotlights focussed on the place where Hitler entered the arena. The lights then moved with the dictator as he made his way slowly to the podium, followed by a suitably large procession of loyal party members. As Hitler approached the podium, music blared out from multiple bands, orchestras, and loudspeakers, music which always included a movement from a symphony by Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). The music was often drowned out by the spontaneous cheers and applause of the crowd. Hitler, a master of manipulating audiences, would only start to speak when absolute quiet reigned once more throughout the stadium.

The massed gathering of Nazi supporters were always made to wait for Hitler to make his appearance, a deliberate tactic to heighten the anticipation and palpable tension in the stadium. At least while the crowd fidgeted on their seats, they had much to admire besides the gigantic proportions of the stadium itself. Massive gold-painted eagles clutching swastikas (and later globes when Hitler dreamed of world domination), perfectly-timed marching paramilitaries in their brownshirts (the SA) and their blackshirts (the SS), adoring cohorts of the Hitler Youth, great masses of torch bearers, and 25,000 colourful banners representing all of the Nazi organisations across the Third Reich. All of this theatrical organisation and close choreography emphasised the message of Nazi control. The crowd, though, had come to see and hear one thing only: Hitler's speech.

Hitler's Speeches

Hitler's speeches at Nuremberg (or indeed anywhere) were less about meaningful content and more about creating a dramatic impact using a mishmash of stereotypes, rhetorical devices, and emotionally-charged language. Hitler was himself a great believer in the power of speech, as noted in Mein Kampf: "All great, world shaking events have been brought about not by written matter but by the spoken word" (McDonough, 117). In each year's speech, Hitler would expand on particular themes closely related to the title of that year's rally such as "Freedom", "Work", "Honour", and "Greater Germany".

Hitler's stream of words were expertly punctuated with pregnant silences, emphatic facial expressions, and dramatic gestures, the latter often copied from the silent film stars of the period and diligently rehearsed by Hitler in front of a mirror.

Below is a typical opening from one of the Führer's speeches:

So you have come this day from your little villages, your market towns, your cities, from mines and factories, or leaving the plough, to this city. You come out of the little world of your daily struggle for life, and of your struggle for Germany and for our nation, to experience this feeling for once: Now we are together, we are with Him and He is with Us, and now We are Germany.

(Stone, 78)

Hitler usually focussed on culture and general themes, urging the people on to greater efforts to make Germany great again and ranting against the "enemies" of the state such as foreign powers and Jews. Hitler did sometimes use his Nuremberg speech to make significant announcements regarding Nazi policies. For example, at the 1935 rally, he announced the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, which prohibited marriages between those defined by the state as Jews and those defined as Aryans. At the same rally, he announced the Reich Citizenship Law, which stripped those defined as Jews of their German citizenship and the Law for the Protection of the Genetic Health of the German People, which stipulated that anyone wishing to get married first had to have a medical examination to obtain a certificate of good health.

The Nuremberg rallies certainly intoxicated the party-faithful, but they were so well choreographed that very often neutral foreign visitors found themselves irresistibly carried away on a wave of hysteria by Hitler's rhetoric. Michael Burn, a visiting British journalist, witnessed the 1935 rally and wrote about it in a letter to his mother:

The Party Rally finished this morning. I cannot really think coherently after this week. It has been wonderful to see what Hitler has brought this country back to and taught to look forward to. I heard him make a speech yesterday at the end of it all which I don't think I shall ever forget and I am going to have translated.

(Boyd, 162)

For William L. Shirer (1904-1993), the celebrated historian of the Third Reich who witnessed Hitler at Nuremberg, the rally was an "exhausting week of parades, speeches, pagan pageantry and the most frenzied adulation for a public figure this writer had ever seen" (230).

For those who could not be present in person, there were the radio broadcasts. The Nazis had, since 1933, promoted the manufacture of cheap radios sets (Volksempfänger), with the fiendish catch that they could only pick up one radio station, the official Nazi one. Millions of households bought these radios and listened to the Nazi broadcasts, often in communal gatherings set up especially so that people could listen together to their leader. Other ways to catch glimpses of the wonders of Nuremberg were the short newsreels and the official feature films shown in cinemas. An important propaganda film of one of the Nuremberg rallies (the 1934 edition), Triumph of the Will, was personally supervised by Hitler and directed by Leni Riefenstahl (1902-2003), the only woman officially involved in the organisation of the rallies.

The last Nuremberg rally was held in September 1938. The rally planned for September 1939 was cancelled at the last minute after Germany invaded Poland that month and WWII began. Ironically, this festival of Nazi smoke and mirrors was to have been called the ‘Rally of Peace'.