The Nuremberg trials (1945-6), held in Nürnberg (Nuremberg), Germany, were a series of trials involving the senior surviving Nazis to hold them accountable for waging war and committing war crimes and crimes against humanity during the Second World War (1939-45). 22 Nazis were tried, with 19 found guilty and sentenced to either death by hanging or lengthy prison terms.

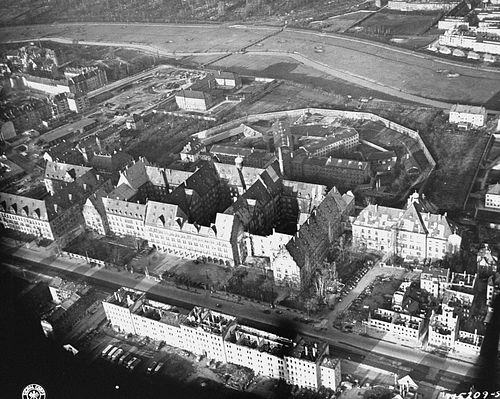

The first Nuremberg trials were conducted from November 1945 to October 1946, and then, a second phase, which involved a much larger number of defendants, was conducted from November 1946 to April 1949. The Nuremberg trials were the first in history where the victors in a war sought to make senior figures from the losing side accountable for their actions. The trials were filmed and contributed greatly to our understanding of how WWII was conducted and revealed both the irrefutable evidence for and enormous scale of such atrocities as the Holocaust. The first month of the trials, the initial proceedings only, were hosted in the Supreme Court Building in Berlin, but they moved on 20 November to the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg. The Palace of Justice was selected because it had been the heart of Nazi show trials against enemies of the Third Reich, the city was the home of the Nuremberg Rally, the infamous annual Nazi Party congress, and the complex had the practical advantage of an adjoining prison where the defendants were detained.

The International Military Tribunal

At the close of WWII, the victorious Allies of France, Britain, the United States, and the USSR, as agreed by their respective leaders at a conference in Moscow back in October 1943, jointly formed an International Military Tribunal (IMT) to bring German Nazi war criminals to justice. There were some calls to have judges from neutral nations head the IMT, but the allied leaders were determined to be directly involved in getting their pound of flesh. The idea of the trials was supported by a number of other nations besides the four main powers.

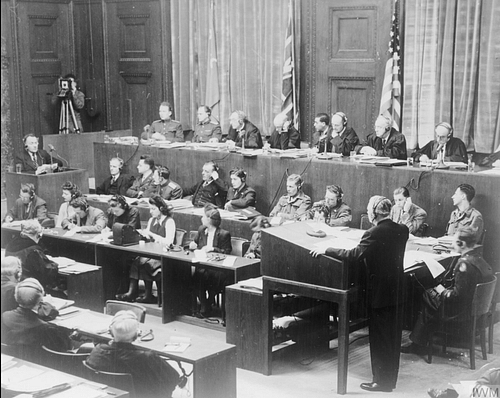

The panel that would decide the fate of the defendants brought before the IMT consisted of one judge and one prosecutor from each of the four nations mentioned above. The judging panel was presided over by the British judge Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, described by one American lawyer as "like God...Hollywood would have cast him" (MacDonald, 23). The chief Soviet judge was I. T. Nikitchenko, the French lead judge was Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, and the US judge was Francis B. Biddle. The legal proceedings followed the common law practice applied in the United States and Britain. Translators worked in the courtroom, and everyone present had access to a set of headphones. There was a large screen to show the court relevant film clips and statistical information. 250 journalists attended the court sessions, and the whole proceedings were filmed and sound recorded.

In the closing stages of the war, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945), and Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) had all committed suicide, but there remained 24 senior Nazi figures whom the Allies were determined to bring to justice. The group was selected not only for their individual roles but also as representatives of particular Nazi institutions. Before the trials could begin, Robert Ley (1890-1945), head of the German Labour Front, committed suicide, and Gustav Krupp (1870-1950), an industrialist who had used forced labour, was considered too physically frail to stand trial. The 22 remaining defendants faced four charges, as expressed in the Oxford Companion to World War II, they were:

- Count 1: Contributing to a common plan or conspiracy to wage war

- Count 2: Crimes against peace

- Count 3: War crimes (e.g. violations of the Geneva Convention such as the abuse and murder of prisoners of war, use of prisoners for labour, destruction of private property, and devastation of property and places with no military justification)

- Count 4: Crimes against humanity (e.g. the murder of civilian populations, use of slave labour, the forced deportation of civilians, and the persecution of specific social, political, religious, and racial groups)

Counts 1 and 2 proved problematic to define, and therefore it was difficult to find the defendants either innocent or guilty of them. This is hardly surprising considering the debate amongst historians ever since as to why and how WWII started and how far one should go back exactly in order to discover the causes of WWII, causes which could be attributed in some cases to both the victors and losers. The court essentially considered counts 1 and 2 as involving actions such as breaking international treaties and invading and occupying free countries. Much easier to establish were cases of counts 3 and 4, although even here there was the added complication that the victors had themselves been guilty of what would today be called war crimes, for example, the Allied bombing of Germany, submarine attacks on unarmed vessels, and the Katyn Forest massacre of Polish prisoners of war by USSR forces. Certain facts were taken as given, such as that Hitler had fully intended to start a world war. In addition, such Nazi organisations as the Gestapo (secret police), the SS (Schutzstaffel), and SA (Sturmabteilung) were condemned as criminal organisations.

The judges not only benefitted from the cross-examination of the defendants but also the testimony of around 360 witnesses (including both victims of and members of the Nazi regime) and a huge quantity of incriminating documents, official and otherwise, including indisputable photographs, sound recordings, and films, such as those taken at concentration and death camps. As noted by Dr Robert Kempner, a lawyer who had fled the Nazi regime:

One of the biggest helps to us was the German bureaucratic sense – they kept everything and they even made publications and films and lot of material had been discovered by our Allied search teams. Some of the people like General Governor Frank of Poland was so anxious to show his friend Hitler after the war what he has done that he kept diaries, volumes and volumes and volumes. In fact he had written his own indictment.

(Holmes, 593)

It is important to note, however, that the documentation for Nuremberg was compiled in order to support the legal case that the defendants were guilty of one or more of the four counts (and not to create a comprehensive reconstruction of past events as, say, a historian would do). There was, too, a degree of negotiation between the various national judges regarding particular defendants – the USSR judge, for example, wanted Rudolf Hess hanged while his fellow judges preferred a prison sentence – but there was a conscious effort on all parties to deliberate with as much fairness as possible given the seriousness of the trials and the world's scrutiny of them. To this end, the defendants were collectively represented by a legal counsel, Otto Kranzenbühler, and permitted individual lawyers to present their defence.

List of Nuremberg Defendants & Verdicts

The men on trial at Nuremberg, their titles or roles, final judgement, and sentences were:

- Hermann Göring (1893-1946) – Reichsmarschall – Guilty (all 4 counts), death by hanging

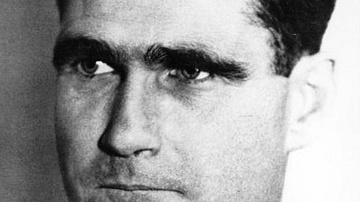

- Rudolph Hess (1894-1987) – Nazi Party Deputy Leader – Guilty (counts 1 & 2), life imprisonment

- Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893-1946) – Foreign Minister – Guilty (all 4 counts), death by hanging

- Wilhelm Keitel (1882-1946) – Field marshal – Guilty (all 4 counts), death by hanging

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-46) – Chief of the Reich Main Security Office – Guilty (counts 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946) – Racial theorist – Guilty (all 4 counts), death by hanging

- Hans Frank (1900-1946) – Nazi Chief in Poland – Guilty (counts 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Wilhelm Frick (1877-1946) – Minister of the Interior – Guilty (counts 2, 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Julius Streicher (1885-1946) – Nazi regional leader – Guilty (count 4), death by hanging

- Walther Funk (1890-1960) – Nazi minister – Guilty (counts 2, 3 & 4), life imprisonment (released 1957)

- Hjalmar Schacht (1877-1970) – Reichsbank President and Minister of Economics – Not guilty.

- Karl Dönitz (1891-1980) – Head of German Navy – Guilty (counts 2 & 3), 10 years imprisonment

- Erich Raeder (1876-1960) – Head of German Navy before Dönitz – Guilty (counts 1, 2 & 3), Life imprisonment (released 1955)

- Baldur von Schirach (1907-1974) – Head of Hitler Youth and Nazi regional leader – Guilty (count 4), 20 years imprisonment

- Fritz Sauckel (1894-1946) – Nazi regional leader – Guilty (counts 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Alfred Jodl (1890-1946) – Chief of the Army's Operations Staff – Guilty (all 4 counts), death by hanging

- Martin Bormann (1900-1945) – Tried in absentia since his death was unknown at the time – Hitler's personal secretary – Guilty (counts 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Franz von Papen (1879-1969) – Former chancellor and ambassador to Turkey – Not guilty

- Artur Seyss-Inquart (1892-1946) – Nazi Chief in the Netherlands – Guilty (counts 2, 3 & 4), death by hanging

- Albert Speer (1905-1981) – Armaments Minister – Guilty (counts 3 & 4), life imprisonment (released 1966)

- Konstantin von Neurath (1873-1956) – Foreign Minister before von Ribbentrop – Guilty (all 4 counts), 15 years imprisonment (released in 1954)

- Hans Fritzsche (1900-1953) – Propaganda minister – Not guilty

The defendants were given IQ tests, with Seyss-Inquart and Schacht outperforming a poor field (Streicher was bottom with a score of 102). Göring was by far the most charismatic of those on trial, and he eloquently justified his past actions, although, in the process, he did no more than reveal his total lack of conscience for the gravity of them. According to Speer, Göring told him he was convinced the "victors would undoubtedly kill him but that within fifty years his remains would be laid in a marble sarcophagus and he would be celebrated by the German people as a national hero and martyr" (Speer, 681). Those who had belonged to the army or navy remained adamant that they should not be on trial at all since they were obeying military orders. Similarly, the civilians believed their actions, no matter how despicable, had been covered by the oath of loyalty they had once been obliged to swear to Hitler. Others pointed out that those in government should not be judged by standards usually applied to private individuals. Another argument of defence was that the victors had no legal right to put the losers on trial in the first place. Some, like Rosenberg and Streicher, were, in any case, completely unrepentant of their past actions.

The simplistic, brutal thinking, or rather lack of thinking, of SS men like Kaltenbrunner and Frank was self-evident. Frick refused to testify at all during his trial. Speer cleverly tried to distance himself from his simpler and more notorious colleagues, constructing for himself a case that suggested he had merely been sucked into Nazism by Hitler's powerful personality. Indeed, Speer was one of the few to accept his guilt (although he is now known to have lied about his lack of knowledge of the Holocaust), or at least accept his part in what he described as a "collective responsibility" (Dear, 808) for the war and its consequences. Finally, Hess seemed on the fringes of lunacy, although he was not clinically diagnosed as insane. Hess annoyed Göring, his immediate neighbour in the dock, with his constant fidgeting and odd bursts of laughter.

All in all, the 22 men looked rather pathetic in their civilian suits. Speer noted the effect of the absence of costume: "For years I had been accustomed to seeing all these defendants in magnificent uniforms, either unapproachable or jovially expansive. The whole scene now seemed unreal; sometimes I imagined I was dreaming" (678). The public and press were also surprised by how ordinary these arch-criminals looked. The novelist Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966) noted that only Kaltenbrunner looked anything like a criminal.

Each defendant was tried in turn, and even those who were cockiest at the beginning, such as Göring, were effectively silenced by the overwhelming mass of evidence against them. Indeed, the evidence was often so horrific and so repetitive that some journalists questioned the necessity of presenting it in such a methodical manner. Ultimately, through the course of the trial, the majority of the defendants themselves realised, if they had not done so already, that they had no defence against the charges brought before them.

Final Sentences

The defendants finally heard their fate on 1 October 1946. Göring committed suicide by swallowing a potassium cyanide pill a few hours before he was to be hanged. Göring's body was cremated, and his ashes were thrown in the ordinary rubbish. Those others who had been sentenced to death were hanged two weeks later on 16 October in the prison at Nuremberg. As a soldier, Keitel asked to be shot, but his request was denied. The bodies of the hanged men were cremated, and their ashes were scattered on the estuary of the Isar River. Those given prison terms at Spandau Prison in Berlin served various lengths of those terms, depending on their health. The last prisoner was Rudolph Hess, who committed suicide at the age of 93.

Subsequent Proceedings

From November 1946 to April 1949, a further 185 Nazi war criminals faced trials organised by the United States military. These trials, conducted alone by the US authorities, are known as the US Nuremberg Military Tribunals. The majority of the defendants faced charges related to the inhuman treatment of, medical experimentation upon, and murder of civilians in Nazi concentration camps and the exploitation of civilians as labourers in industry. Of these defendants, 131 were found guilty, with 24 receiving the death sentence and the rest given prison terms.

There were other post-WWII trials of war criminals, notably the Far East war crime trials, which dealt with Japanese war criminals, and trials in specific countries, particularly in Poland and the USSR. Germany conducted several denazification trials. There were also some reversals of earlier verdicts. Schacht was sentenced to eight years of hard labour (but only served two), while Alfred Jodl was exonerated by a German denazification court in 1953. By 1949, "the Allies had convicted 5,025 people" (Hite, 341).

Many Nazi war criminals escaped capture, but the search for them went on, and some were ultimately brought to justice, often decades later. Such a figure, one of the chief administrators of the Holocaust, was Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962), apprehended in Argentina in 1960, tried in Israel, and then hanged.

The legacy of the Nuremberg trials and those which followed included raising awareness of the victims of Nazism and establishing a framework on which international laws could be agreed upon. These laws could be used to hold leaders responsible for their actions and act as a deterrent to war crimes being committed. The Nuremberg trials provided a precedent, for example, for the trial of war criminals following the conflicts in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.