Oda Nobunaga was the foremost military leader of Japan from 1568 to 1582. Nobunaga, along with his two immediate successors, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), is credited with unifying medieval Japan in the second half of the 16th century. An innovative general who also used diplomacy as well as superior military tactics and weapons to see off his rivals, the warlord was infamous for his ruthless drive to conquer all before him.

Rise to Power

Born into a family of local administrators in 1534, Nobunaga's father, Oda Nobuhide (1510-1551) was a minor feudal lord or daimyo in Owari Province, central Japan. Nobunaga would first come to prominence when, on his father's death, he became the lord of Nagoya castle. Using the castle as his base, Nobunaga extended his domination over rival daimyo with notable successes coming in 1555 when he razed the town of Kiyosu and in 1559 when he captured and obliterated the fortress of Iwakura. The warlord's reputation for ruthlessness was firmly established in 1557 when he ordered the murder of his own brother. In 1560 at the Battle of Okehazama, the warlord of Mikawa, Imagawa Yoshimoto (1519-1560), was defeated and killed when Nobunaga's outnumbered army sprang a surprise encirclement of the enemy. Nobunaga was well on his way to becoming Japan's most-feared military leader.

Nobunaga is the subject of two biographies in Japanese history, the first was Shincho koki by Ota Gyuichi, which was published in 1598, while the second, Shincho Ki, was published in 1622 and was compiled by Oze Hoan as an extension of the earlier work. Both works glorify their subject and, as with similar posthumous biographies of the medieval period, exaggerate the deeds of the famous daimyo and insert episodes of legend which likely never happened at all. The Jesuit missionary and historian Luis Frois (1532-1597), however, gave a much more revealing description of Nobunaga in the following extract from a letter written in 1569:

A tall man, thin, scantily bearded, with a very clear voice, much given to the practice of arms, hardy, fond of the exercise of justice, and of mercy, proud, a lover of honour to the uttermost, very secretive in what he determines, extremely shrewd in the stratagems of war, little if at all subject to the reproof, and counsel of his subordinates, feared, and revered by all to an extreme degree. Does not drink wine. He is a severe master: treats all the Kings and Princes of Japan with scorn, and speaks to them over his shoulder as though to inferiors, and is completely obeyed by all as their absolute lord.

(Keen, 1159)

Unifying Japan

Nobunaga eventually took control of the capital Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 1568 where he installed Ashikaga Yoshiaki as his puppet shogun, who would be exiled five years later for conspiring with Nobunaga's enemies, thus bringing an end to the Ashikaga shoguns which had reigned since 1388. In 1579 and now in control of all central Japan, Nobunaga established a new headquarters at the magnificent Azuchi castle outside the capital on the edge of Lake Biwa. Nothing remains today of the castle except its stone base, but it was the first to have the huge multi-storey tower keep that became the norm in Japanese medieval castles.

Nobunaga was able to defeat rival warlords and expand his territorial control thanks to his large army which was well-equipped and which included the gifted general Toyotomi Hideyoshi (who would become Nobunaga's successor). Nobunaga was an innovator as he was one of the first Japanese leaders to adopt firearms. Around 1549, when Nobunaga was a mere 15-year-old commander, he had created a specialist corps of 500 men each with his own matchlock muskets. This unit was sent into battle ahead of the other troops, and they proved decisive at the siege of Muraki castle in 1554 and at the Battle of Anegawa in 1570. Seeing their effectiveness, the corps was increased to 3,000 men and once more brought a victory, this time at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575. Nobunaga used his new weapons well, too, and was the first to employ rotating ranks of musket-men to create a continuous volley of fire. Nobunaga's army was also the first to have each man, including the infantry, issued with a full suit of armour. The territories Nobunaga gained were given to his loyal commanders to govern, and the lands of captured warlords were frequently redistributed and relocated to break old ties of loyalty.

In order to secure his grip on power, Nobunaga attempted to reduce the income of his rival daimyo by abolishing the tolls on all roads. He boosted his own coffers by minting the first Japanese currency since 958 and standardising the exchange rates between all the different coins then in use. Another lucrative source of cash was to release merchants from their guilds and have them pay the state a fee instead. From 1571 an extensive land survey was begun to make the tax system more efficient. Another policy was to confiscate all weapons held by the peasantry from 1576 onwards, the so-called 'sword hunts.' Meanwhile, Nobunaga continued to expand his territory, his goal was nothing less than a unified Japan. Not for nothing did the warlord emblazon on his personal seal 'Tenka Fubu' or 'a Unified Realm under Military Rule.'

Attitude to Religions

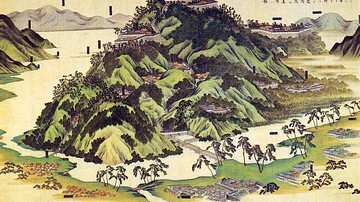

In another strategy to weaken his opponents, Nobunaga did not hesitate to destroy any Buddhist temples and execute influential Buddhist priests that were associated with or allied to any of his rivals. The most infamous example of this policy was his destruction of the Enryakuji monastic complex on the sacred Mt. Hiei near Kyoto in 1571. Nobunaga was concerned at the power of the monastery and its large army of warrior monks who still descended from the mountain whenever they felt they were not receiving their share of state handouts. Nobunaga had his troops surround the slopes of Mt. Hiei and set fire to the forest which destroyed the temple and killed 25,000 men, women, and children. Enryakuji would do better under Nobunaga's successors, and it was restored to its former glory from 1595.

Another influential Buddhist temple-fortress, Ishiyama Honganji in Osaka, was destroyed in 1580 by Nobunaga's fleet of cannon-toting ships. Toyotomi Hideyoshi would later build his famous Osaka castle on its ruins. The result of this onslaught on the major Buddhist temples was that it finally ended their influence on government and regional powers, a position of privilege they had enjoyed throughout the medieval period.

Regarding other religions, Nobunaga encouraged the work of Christian missionaries in Japan as he saw the benefit of European contacts which brought trade and technology such as the firearms he put to such devastating use. The warlord was also keen on having people worship himself as a divinity and built a temple for that purpose. In another strategy to build himself a cult of leadership, he declared his birthday a national holiday. Curiously, Nobunaga did not go in for ostentatious clothing and although his dress sense was unusual he did set a trend, as one eyewitness account relates:

He always strode around girded about with a tiger skin on which to sit and wearing rough and coarse clothing; following his example everyone wore skins and no one dared to appear before him in court dress. (quoted in Mason, 185)

Nobunaga promoted the arts, notably Kowaka drama and the Japanese Tea Ceremony, calling upon the skills of the recognised number one expert in this latter area, Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591).

Betrayal & Death

On 21 June 1582, while Nobunaga was about to set off on campaign in western Japan he met his sticky end at Honno-Ji temple (Honnoji) in Heiankyo. The warlord was betrayed by one of his vassal allies, Akechi Mitsuhide, who was also the liaison officer between Nobunaga and his puppet shogun Yoshiaki. In an episode known as the Honnoji Incident, Mitsuhide, for reasons unknown, launched a surprise attack on Nobunaga's position and, according to one version of the story, when it became clear that his capture was imminent, the man who then controlled half of Japan committed suicide. In a different version, the warlord died in flames as the temple burnt down - some might say in an act of divine retribution for his own burning of Enryakuji. Nobunaga's son and chosen heir, Nobutada, died in the same disaster.

Nobunaga's death would be avenged swiftly when his foremost general Totoyomi Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki and declared himself Nobunaga's successor. Hideyoshi would continue his predecessor's plan of unifying Japan, a process which was not finally completed until the rule of Hideyoshi's own successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who established the Tokugawa Shogunate from 1603 which finally gave Japan some 250 years of peace. As the old Japanese saying goes, "Nobunaga mixed the cake, Hideyoshi baked it, and Ieyasu ate it" (Beasley, 117).

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.