Old Testament is the Christian name for the books of the Jewish scriptures that constitute the first half of the Christian Bible. "Old" in this sense was a means to distinguish Judaism from Christianity at the creation of the New Testament beginning in the 2nd century CE Jewish believers do not consider their scriptures old, as in no longer valid; they remain at the center of Jewish life and practice.

Etymology

"Testament" became the English translation for a shared religious and cultural concept in the ancient world, that of "covenant." A covenant was a legal contract upheld and sworn to by oaths and rituals. We have examples between overlords and constituents. The Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE) and the Hittite king, Hattusili III, signed such a covenant in 1259 BCE. Both called upon their distinct gods to validate the agreement, an early example of a peace treaty after the Battle of Kadesh.

The Hebrew for covenant, beriyth, meant a promise or a pledge but may also have derived from a root word that meant "cutting." Covenants were "sealed," legally attested, by passing cut pieces of the flesh of sacrifices between the parties. It may also have been derived from ancient Akkadian, for "between," an agreement between people.

In the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures, beriyth became diatheke, a Greco-Roman concept of jurisprudence, "agreement," "will," that described "a last will and testament." The King James version used the English "testament" for the biblical books, understanding God's covenants as eternal. We still refer to someone's "last will and testament," directions for the disbursement of their property and assets, as legally binding.

All ancient religions had contracts between their gods and humans. The contract detailed the relationship between society and the divine. Covenants had two essential elements: 1) the god's promise to help the community to prosper in return for worship, which meant the sacrifices, and 2) law codes that detailed behavior and gender roles. Law codes were manifest in forms of governing, originally through kings, and were validated by the fact that they were given by the gods. There was no distinction between divine and civic laws. Elected Roman magistrates carried the power of imperium, the religious authority and duty to carry out the dictates of the divine.

The Jewish Scriptures

Sometimes referred to as the Hebrew Bible, the Jewish scriptures consist of many and varied sources: myths, hymns, prayers, oracles, and historical narratives. The consensus is that the stories began as oral tradition and were passed down over several generations. As the centuries passed and Israel experienced a long history, which included many momentous events as well as disasters, these oral stories were edited with added material. The additions always reflect the meaning of the older narratives, updated to explain contemporary events. The consensus is that older, oral traditions were first written down c. 600 BCE where the various sources were brought together.

The ancients respected antiquity, the ancient past, in that it provided validation of concepts and customs handed down through the generations. After the death of Solomon (c. 930 BCE), Israel split into two kingdoms, Israel in the north and Judah in the south, each with their own traditions. In the first writing down of various sources, the variations were maintained. Thus the written version of the Hebrew Bible contains duplicates and triplicates of the same stories that also have contradictions. For example, there are two different stories of creation in Genesis and two different stories of the flood and Noah.

The books are dated according to specific cultural details in the stories. Many of the stories in Genesis reflect Middle Eastern nomadic culture in the late Bronze Age. Later stories reflect known historical events, such as the invasion of the Assyrians in 722 BCE and the Babylonian destruction of Solomon's Temple and Jerusalem in 587 BCE.

A characteristic of all ancient religions was the absence of a central authority that could dictate what all people should believe or practice. Hundreds of native cults incorporated ancient divinities and then added new gods and rituals as they arose over time. Similarly, various groups of Jews (Jewish sects) held different concepts and practices. The sacrifices and purity rituals were listed in the book of Leviticus for the Temple, but we have little knowledge of how they were observed in Jewish synagogues throughout the Roman Empire. A written text does not necessarily indicate conformity. Then (as now), people consulted their religious texts and interpreted them in individual ways.

Covenants in the Hebrew Bible

Two types of covenants are prevalent in the Hebrew Bible: unconditional or eternal covenants by God, and conditional covenants. Despite changing circumstances, the original covenants remained intact and were often repeated. However, with conditional covenants, it was God's choice to punish violations (sins) against his dictates. Violations were collectively categorized as allowing the sin of idolatry, which also led to lifestyle sins. We have a pattern in the scriptures. Because of their sins, God permitted the Israelites to be oppressed by local or foreign rulers. The Israelites appeal to God, promising to hold to his covenants. God then intervenes by rescuing them from their oppressors and restoring the original dictates.

Recurring patterns were a literary device imposed by the writers. Historically, we cannot confirm that the Israelites always sinned through idolatry. The stories served as explanations for periodic crises (times of evil) and the restoration of God's promises.

The Covenant with Noah

One of the earliest concepts of covenant was in the story of Noah and his family surviving the great flood:

Then God said to Noah and to his sons with him, "As for me, I am establishing my covenant with you and your descendants after you and with every living creature that is with you ... as many as came out of the ark I establish my covenant with you, that never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of a flood, and never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth."

(Genesis 9:8-11)

Covenants were often represented by an omen or a sign, in this case, a rainbow.

I have set my bow in the clouds, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. When I bring clouds over the earth and the bow is seen in the clouds, I will remember my covenant that is between me and you and every living creature of all flesh, and the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh.

(9:13-15)

The Covenant with Abraham

One of the most important covenants was between God and Abraham"

Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘"Go from your country and your kindred and your father's house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed."

(Genesis 12:1-3)

The covenant emphasized both prosperity (flocks and herds) and people in exchange for Abraham's obedience to the dictates of God. A change of worldview often resulted in a new name. Thus, Abram became Abraham. Abraham meant "father of the multitudes," "father of the nations." As he did in everything, Abraham became the ideal of faithfulness (loyalty to God) for both Jews and Gentiles in both Testaments.

The sign of this covenant is found in Genesis 17:9-14:

God said to Abraham, ... "This is my covenant, which you shall keep, between me and you and your offspring after you: Every male among you shall be circumcised. You shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskins, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and you. Throughout your generations every male among you shall be circumcised when he is eight days old, including the slave born in your house and the one bought with your money from any foreigner who is not of your offspring. So shall my covenant be in your flesh an everlasting covenant. Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant."

Circumcision is often understood to be connected with the modern concept of hygiene. However, the ancients lacked this level of medical knowledge. Circumcision was and is practiced by many people around the world. Egyptians, Syrians, and Arab tribes (through the descent of Abraham) also circumcised men. Our best understanding is the way in which circumcision functioned in the Bible; it was a permanent, physical symbol that became one of the identity markers of ethnic Jews.

Later traditions read being "cut off from his people" as a punishment for not following the covenants as symbolic of the Israelites living "in exile," cut off from the promised land of Canaan, captives in a foreign land. It also became an analogy for alienation from God.

The Covenant with Moses

The covenant with Abraham did not contain specific details of how to carry out the worship of God. Details were provided in the ultimate covenant between God and Moses on Mt. Sinai after the escape from Egypt (Exodus 20). They are known as the ten commandments, because the first ten are highlighted at the beginning. But this was followed by 603 other commandments. The first ten were absolute, while the others had detailed methods of "atonement," or a series of rituals and sacrifices to undo violations.

This covenant presented the Israelites with a constitution for the nation of Israel. It contained details on how they were to be "set apart" from the other nations in their worship, appearance, and specific laws on everyday behavior and relationships with each other: "For you are a people holy to the Lord your God; the Lord your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on earth to be his people, his treasured possession" (Deuteronomy 7:6). Moses was commanded to place the tablets of the laws in the ark of the covenant, housed in a tent shrine.

Details of the Mosaic covenant continued in Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Collectively, throughout the scriptures, they were referred to simply as the Law of Moses.

The Covenant with King David

The books of Joshua and Judges related the settlement of the Israelites in Canaan after their escape from Egypt. In this period, the Israelites were ruled by the descendants of the twelve sons of Jacob in a tribal confederation. At that time, the ark of the covenant was kept in various tribal cult centers so that no one tribe dominated the others.

1 and 2 Samuel relate the history of the rise of kingship in ancient Israel. Samuel the prophet had anointed David with oil to replace the first king, Saul. When David became king, he consolidated the tribes for a united monarchy, centered in Jerusalem. He had plans to bring the tent of meeting into the city and build a permanent, stone "house" for God. But David committed adultery and murder in his relationship with Bathsheba.

The prophet of record for David's rule was now Nathan:

For you, O Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, have made this revelation to your servant, saying, "I will build you a house" . . . now, therefore, may it please you to bless the house of your servant so that it may continue forever before you, for you, O Lord God, have spoken, and with your blessing shall the house of your servant be blessed forever" (2 Samuel 7:27-29).

David would not build a house for God; that was left to his son, Solomon. Nathan's announcement created the concept of a dynasty of David's descendants. There would always be an heir of David on the throne of Israel. From the Hebrew mashiach ("anointed one"), we have "messiah" (in Greek, christos). The later prophets claimed that when God established his kingdom on earth, he would raise up a messiah from the line of David. There is no special sign in this covenant, but "house" is symbolic of a throne, a symbol of rule.

The Septuagint Bible & Canon

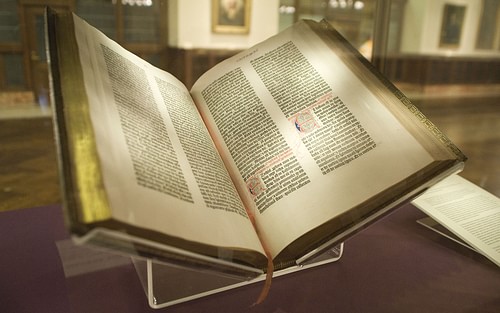

The ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-247 BCE), commissioned a translation of the Hebrew scriptures to koine Greek for his Jewish community in Alexandria. The Septuagint Bible ("the translations of the seventy"), was the version used by the writers of the gospels.

A later term to describe biblical books is "canon." "Canon" was a Greek word that meant "measurement," applied to the eventual decision to 'measure', which books were deemed sacred scriptures and which were not. The Jewish scriptures took centuries to decide the official canon.

We do have an early concept of what could be understood as a canon. In his history of Judaism compiled for Romans, the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE) rationalized the collection:

For we have not an innumerable multitude of books among us, disagreeing from and contradicting one another, [as the Greeks have,] but only twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine; and of them five belong to Moses, which contain his laws and the traditions of the origin of mankind till his death. This interval of time was little short of three thousand years; but as to the time from the death of Moses till the reign of Artaxerxes king of Persia, who reigned after Xerxes, the prophets, who were after Moses, wrote down what was done in their times in thirteen books. The remaining four books contain hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life. ... How firmly we have given credit to these books of our own nation is evident by what we do; for during so many ages as have already passed, no one has been so bold as either to add anything to them, to take anything from them, or to make any change in them; but it is become natural to all Jews immediately, and from their very birth, to esteem these books to contain divine doctrines, and to persist in them, and, if occasion be willingly to die for them

(Against Apion, Book 1:8).

Decisions on the canonization of the Jewish scriptures were not always based on theological differences per se. Manuscripts were examined for provenance and the authority of the writer. There are dozens of manuscripts that became categorized as Apocrypha, from a Greek term that meant "hidden away," or "kept secret." Many of these books were written by "seers" who went into an ecstatic trance and experienced out-of-body journeys with revelations of the final days, with tours of heaven and hell on the fate of the righteous and the wicked. They contain elements from the Greek schools of philosophy, highlighting the destiny of the soul. They are quite esoteric and may have been beyond the average, uneducated person. Modern study Bibles include the books of the Apocrypha immediately following the Jewish scriptures, between the testaments.

The ultimate canon of the Jewish scriptures does not contain the four books of the Maccabees, written at the time of the Maccabean Revolt against the oppression of Greek kings. The Maccabee literature introduced the concept of martyrdom, the reward a martyr who sacrificed their life for their beliefs and was translated to heaven. Martyrdom remains an important concept in Judaism.

That the books were not included in the final canon may have been due to historical or political reasons. The leaders of the revolt established the Hasmonean dynasty. Josephus described the various sects of Jews, many of whom opposed the rule of the Hasmoneans, particularly the Pharisees. This may have been one of the reasons that the Maccabee books were not included in the final canon.

The oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible are determined largely from archaeological excavations and discoveries in ancient libraries. The library of the Essenes had manuscripts of every book in the Jewish Bible with the exception of Esther; these are Dead Sea Scrolls.

The later Rabbis of the 2nd to 5th centuries added commentaries on the laws and the historical narratives. Over time, the Jewish tradition used the acronym of Tanakh for their scriptures"

- T for Torah (instruction), the first five books of the Pentateuch

- N for Nevi'im, (prophets)

- K for Ketuvim, (sacred writings): Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and I and II Chronicles.

Modern Christian Bibles that contain the Old Testament vary among the major denominations of Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Protestantism. Decisions on canon include acceptance or rejection of the works of Apocrypha as well as some additional books in the Greek Septuagint.

What comprises the modern canon of Judaism is based upon the Masoretic Text. From the word, massorah ("handed down"), it became an authoritative combination of the Hebrew and Aramaic manuscripts collected between the 7th and 10th centuries CE. The purpose was to standardize the texts, adding letters for vocalization of the vowels as ancient Hebrew only had consonants. The definitive version of the Hebrew Bible contains 24 books.

In modern practice, sections of the Jewish scriptures are read at different times over the course of the year. Many are highlighted during the liturgy, on Sabbaths, and during the religious festivals.