Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), leader of Nazi Germany, attacked the USSR on 22 June 1941 with the largest army ever assembled. The Axis offensive of June-December 1941 was code-named Operation Barbarossa ('Redbeard') after Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1155-90). Despite Axis victories, the Red Army, with larger reserves and better supply lines, remained resilient.

The successful defence of Moscow turned the tide as the invaders failed to cope with the harsh winter conditions, but the German-Soviet war continued for four more years until the USSR won total victory in the spring of 1945.

Why Did Hitler Attack the USSR?

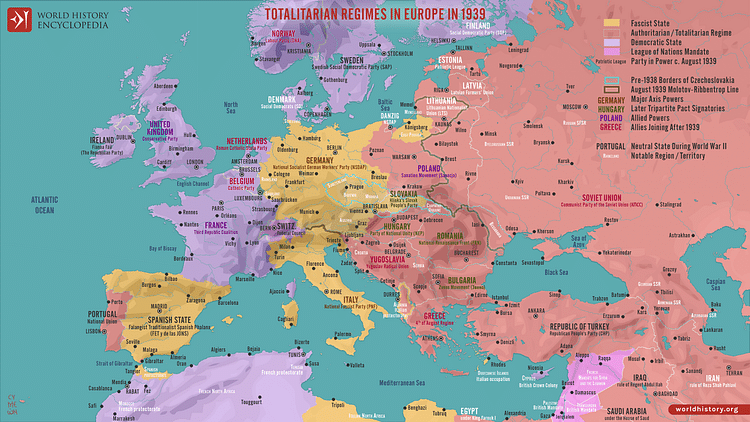

From the 1920s, Hitler identified communism as one of the greatest threats to Germany's prosperity. This sentiment was put to one side when Hitler and the leader of the USSR, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. The agreement included a non-aggression clause that neither state would attack the other since Hitler planned to invade Poland but did not want to face British and French armies in the west at the same time as a Soviet army in the east. Stalin, meanwhile, gained valuable time for rearmament. Secret protocols in the pact allowed Germany and the USSR to attack their neighbours, effectively carving up Central and Eastern Europe between them. The USSR had freedom of action in eastern Poland, Bessarabia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Germany had western Poland and those states to the south. The agreement included trade, the USSR providing raw materials in exchange for Nazi gold.

For both sides, the Nazi-Soviet pact was a temporary agreement of convenience; war between the two seemed inevitable given their ideological differences, Hitler's territorial ambitions, and Germany's need for raw materials. Hitler had written about these ambitions in his 1925 book, Mein Kampf, where he described the need for Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper. Following Hitler's successful invasion of Poland in 1939, Hitler had to deal with Britain and France, who both declared war on Germany. To everyone's surprise, Germany's attacks in the West were remarkably successful. France surrendered in June 1940, and Britain retreated with the Dunkirk Evacuation. Hitler did not win the Battle of Britain in the air (July-October 1940), which meant an invasion against that country could not be launched. Instead, Hitler embarked on a bombing campaign, but when Britain still did not surrender, Hitler turned to the East.

Poland had been split down the line of the River Bug in 1939, with the USSR taking the eastern part and Germany the western side. The USSR made client states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, although Finland stubbornly resisted the Red Army's attacks (a peace treaty was signed in March 1940). One consequence of these land grabs was that the USSR's line of rather neglected defences, the Stalin Line, which protected its western flank, was now far behind what would become the front lines.

Hitler's code name for the attack on the USSR was Operation Barbarossa. The official justification for the invasion was that the USSR had broken the spirit of the Nazi-Soviet Pact through acts of sabotage in German territory and was massing troops to directly threaten the Third Reich. On the other side, Stalin accused Hitler of breaking the pact by mobilising German troops into Romania and Bulgaria. As the historian W. L. Shirer notes, "The thieves…had begun to quarrel over the spoils" (801).

Objectives: A Long Invasion Front

Hitler's army staff had been planning Operation Barbarossa since the summer of 1940. The generals could not quite agree, though, on how to proceed with the invasion. Hitler's plan was to punch through the Soviet lines in the centre and then split his forces to the north and south. The overall objective was clear enough: "to crush Soviet Russia in a swift campaign" (quoted in Dear, 86) by destroying the Red Army. Hitler promised his generals: "We'll kick the door in and the house will fall down" (Stone, 138) in a matter of weeks. Both UK and US military intelligence agreed with this view, believing that the USSR would collapse in 6 or, at the most, 12 weeks.

Specific objectives of Operation Barbarossa were to take Leningrad, occupy resource-rich regions such as the Donbas and other regions in Ukraine, and take the Caucasus oil fields. Moscow was a secondary objective. The lack of a clear, longer-term plan, particularly what to do if the Red Army was not pushed back as far as hoped (the Western Dvina-Dnieper rivers), proved to be a fatal weakness. Another problem was that the Red Army proved to be a lot more resistant than anticipated. Not for the first time, a Western European army would head into the vast depths of Russia unaware it faced not one enemy but three: the opposing army, the problem of logistics, and the harsh winter conditions.

The Opposing Forces

'Barbarossa' was launched at 3.00 a.m. on 22 June. Six hours later, Germany formally declared war on the USSR. The largest army in history, which was experienced, well-organised, and highly confident after its exploits in Western Europe, moved forward on a wide front stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

The Axis army, which included German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men in 153 divisions, 3,600 tanks, and 2,700 aircraft (Dear, 86). The campaign was commanded by Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). The force was divided into three army groups: North, Centre, and South, commanded respectively by Field Marshals Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb (1876-1956), Fedor von Bock (1880-1945), and Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953). There were also three air force groups.

The Soviet army in the west consisted of around 2.9 million men, 10-15,000 tanks, and 8,000 aircraft (Dear, 88). A significant part of their weaponry was inferior, particularly in the area of tanks, many of which were already obsolete, although around 1,800 (the T-34 and KVs) were actually superior to those of the enemy. Only around one-quarter of the Soviet air force's aircraft could be described as modern in 1941. Other weaknesses included a lack of transport vehicles, inferior optics on weaponry, and poor telecommunications backup systems for when standard landlines were severed by the enemy.

Soviet tactics remained too heavily weighted towards the infantry, and tanks were typically used as mere mobile artillery rather than, as in the German panzer divisions, a weapon in their own right. Mid-level Red Army officers were not, unlike their German counterparts, encouraged to show initiative in the field, a factor which often downgraded a battle loss to a total disaster. Stalin took overall command of any Red Army operations and was not slow to remove commanders after setbacks. The commander-in-chief during Operation Barbarossa was Marshal Semyon Timoshenko (1895-1970), another key commander was Semyon Budenny (1883-1973), but the most gifted general of the campaign was Georgi Zhukov (1896-1974), who proved remarkably adept at anticipating the moves his enemy planned to make.

Stalin's intentions are not known with any certainty, but it may be that he expected Germany's campaign in Western Europe to last several years, as it had in WWI, and he was caught off guard by the speed of Germany's victories in the Low Countries and France. Stalin had begun to mobilise his army before the invasion, but the positions emphasised offensive operations, and so, regarding the defence function they would actually be used for, the lines were nowhere near deep enough to absorb full frontal attacks from the enemy. Another issue was that too many Red Army units protruded into the German lines and so were exposed on three sides to the enemy. There were, too, many logistical problems, which ranged from commanders being stuck on trains miles from their troops to artillery units having no ammunition to fire. On the plus side, 4,000 Red Army officers were put back in service after they had been imprisoned following Stalin's purges of the late 1930s. Another major advantage was that Stalin had already organised his industry and economy for total war, something Hitler, believing the Eastern campaign would be as short as the Western one, had not yet seen the necessity for. Finally, the Soviet commanders would learn quickly from their errors. The crucial question was: could the USSR survive the first massive onslaught from the invaders?

Axis Victories

The Axis advance was successful. Air supremacy was achieved within a few days after some 2,500 Soviet aircraft were destroyed, mostly on the ground. Axis troops moved through the defences according to their Blitzkrieg ('Lightning war') plan of combining air support with fast-moving armoured and infantry divisions. The Red Army, surprised not by the attack but by the scale of it, suffered a number of heavy defeats. Several giant pockets of Red Army troops were created behind the front as the Axis tanks sped forward far ahead of their infantry support. These pockets of troops sometimes surrendered en masse, but sometimes they fought their way out with remarkable tenacity. The Axis force was simply not large enough to create tight encircling movements so that time and again the Red Army divisions could withdraw and regroup.

The campaign was a ruthless one, with Axis forces encouraged to follow a scorched earth policy and execute political commissars. The 'Barbarossa Jurisdiction Decree' gave German soldiers the freedom to commit atrocities against Soviet civilians, while special mobile killing squads, the Einstazgruppen, executed Jewish and Slavic people as the front line moved forward. Some historians have suggested that had Hitler developed a more sympathetic attitude to the people he conquered, they might have aided him in his fight with Stalin. The Red Army was equally guilty of war crimes as the fundamentals of the Geneva Convention were entirely ignored.

Stalin reacted to the initial defeats and brutal nature of the campaign by declaring this a 'Patriotic War' where everyone must offer nothing less to the enemy than a 'relentless struggle'. Punishments were imposed on those who did not fight as required, such as Stalin's order that deserters should be summarily shot.

Key Battles

The key battles of Operation Barbarossa included:

- Battle of Białystok-Minsk Jun-Jul 1941

- Battle of Uman Jul-Aug 1941

- Battle of Smolensk in 1941

- Battle of Kiev in 1941

- Battle of the Sea of Azov Sep-Oct 1941

- Siege of Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) Sep 41 to Jan 1944

- Battle of Bryansk Oct 1941

- Battle of Moscow in 1941-2

- Siege of Sevastopol in 1941-2

- Battle of Rostov Nov-Dec 1941

As his advance progressed, Hitler imagined he could hold a victory parade in Moscow in August. He planned the 'Germanization' of the East; large cities were to be destroyed, with their populations eliminated or removed. Hitler was ready to implement his triple objective in the East: rule, administer, and exploit. The Axis army performed huge encirclements of cities, such as at the battle of Białystok-Minsk and the battle of Smolensk in 1941. Hitler then ordered the bulk of his forces to the north around Leningrad and to the south to Ukraine, with the objective of capturing material and industries useful for the war effort.

The Army Group Centre remained on the defensive, a decision which Hitler's generals did not agree with as it allowed the enemy to improve its defences in and around Moscow. The battle of Kiev in 1941 and the capture of 665,000 prisoners was the Axis high point and helped Hitler gain the natural resources that would help the invaders fight on into 1942.

Despite having no sizeable strategic reserves, Hitler seems to have changed his plan, and the Army Group Centre was finally ordered to attack Moscow in October, code-named Operation Typhoon. Again, the campaign got off to a very good start for Hitler with victories at Bryansk and Vyazma. As the Axis forces moved to within 20 miles (32 km) of Moscow, it seemed the Soviet capital with its great railway hub would soon fall into the invaders' hands; even the embalmed body of Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), founder of Soviet Russia, was removed to a place of safety.

The Soviet Fightback

It became clear that the German high command's low opinion of Soviet military capabilities was quite wrong. Even when defeated and suffering tremendous losses, the Red Army still managed to launch repeated counterattacks. The hard lesson of how to resist Axis pincer movements was learned. The retreating Red Army was also very particular in destroying anything that could be of use to the advancing enemy. Nevertheless, the Axis forces seized many industrial sites producing coal, steel, and aluminium. Crucially, Stalin had shifted most manufacturing to the safety of Central and Eastern Russia, and this plan now paid dividends as losses in the field could be replaced and supplies given to troops under sustained attack such as at Moscow or during long sieges like Leningrad in 1941-44 and Stalingrad (Volgograd) in 1942-3.

The Axis armies, meanwhile, faced ever-rising difficulties in getting their supplies, given the great distances involved as they pushed deeper into Russia. As General Hasso von Manteuffel (1897-1978) noted: "The spaces seemed endless, the horizon nebulous. We were depressed by the monotony of the landscape and the immensity of the stretches of forest, marsh and plain" (Stone, 146). Roads were poor or non-existent, bridges were few and far between, and villages had nothing much to offer by way of supplies. German logistics were also severely challenged by Stalin's orders that partisans sabotage Axis supplies whenever and wherever possible.

On top of that, late-autumn conditions in 1941 made what roads there were muddy, and so logistics became extremely difficult for both sides. Even worse for Hitler, now that Japan seemed to be concentrating on the Pacific and so was no longer a threat to the USSR, Stalin was able to bring fresh troops from Siberia and Eastern Russia into the campaign. Moscow remained under threat, but, significantly, Stalin remained there and called for the entire city to become a fortress. The defence of Moscow was orchestrated by Zhukov, who had marshalled his resources for a massive counterattack.

As the Soviet troops steeled themselves to defend their capital, the Axis generals anxiously looked for the coming of winter and rued their inadequate reserves. Operation Barbarossa was not meant to last this long, and now the lack of strength in depth of the invading army, after sustaining massive losses for five months, was beginning to tell. Worse for those men in the field, Hitler had not planned for a winter campaign, and so the troops lacked essential equipment and even the proper clothing. The Axis army literally began to freeze to death.

The End of Barbarossa

The Axis troops had to resist several Soviet counterattacks through December, which pushed the Axis forces some 175 miles (280 km) from Moscow. Operation Barbarossa had grabbed huge swathes of land but had failed in its objective of crushing the Soviet resistance. It had been a bruising encounter between two huge armies. By 31 January 1942, the Axis army "had lost almost 918,000 men, wounded, captured, missing, and dead – 28.7% of the 3.2 million soldiers involved" (Dear, 89). At the same time, "3.35 million Soviet soldiers had been taken prisoner by the Germans" (ibid). It had turned into a war of attrition where the USSR could draw on much deeper resources than the invaders. In addition, the USSR was now helped by the US Lend-Lease programme, which gave aid amounting to around 7% of Soviet industrial production. Hitler had lost his gamble of knocking out the USSR in a few weeks: "the defeat before Moscow was a serious setback, an indisputable failure of the Blitzkrieg concept" (Dear, 89).

The Eastern Front Continues

Hitler was determined to fight on and launched Operation Blue. He had already removed many generals who had wanted to withdraw and made himself the commander-in-chief of the entire army on the Eastern Front in December 1941. As winter turned to spring in 1942, a new phase of the German-Soviet War began. The fighting would go on for another three years. Key engagements included the pivotal Battle of Stalingrad (Jul 42 to Feb 43), the Battle of Kursk (Jul-Aug 1943), the Battle of Smolensk in 1943, and the Warsaw Uprising (Aug-Oct 1944). The USSR's industrial capacity to make war far outstripped Germany's, and Hitler was, from 1943, obliged to divert millions of Axis troops to face the Western Allies' invasion of Italy from July 1943 and D-Day in Normandy in June 1944. The Axis campaign was not helped either by Hitler's refusal to allow any withdrawals, and so commanders were, in the end, obliged to surrender rather than retreat and regroup.

Stalin won his titanic struggle with Hitler. The USSR gained control of Eastern and Central Europe, marched right on to the German capital, and captured it in the Battle of Berlin (April-May 1945). The German-Soviet war accounted for at least 25 million military and civilian deaths, perhaps half of the overall WWII death toll. Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, and Germany surrendered shortly after. Many historians identify Operation Barbarossa as the point where Hitler lost the war. The campaign's legacy has endured. The USSR was determined not to allow such an invasion ever happen again and so reshaped Eastern Europe to that end. Even today, Russian suspicion of European motives continues to influence the continent's geopolitics.