Operation Chastise, the 'Dambusters' raid, was an attack by a squadron of RAF Lancaster bombers on the dams of the Ruhr basin in Germany in May 1943. Led by Squadron Leader Guy Gibson, the bombers breached two dams causing enormous flooding in the valleys below, disrupting industrial targets and killing at least 1,300 civilians.

Although the damaged factories, coal mines, and bridges were soon repaired, the mission showed the value of precision bombing by specially trained crews, diverted German resources to air defence, and reinvigorated Britain's position amongst its allies.

Objectives

The Ruhr basin in Western Germany was saturated with important heavy industry. These factories, many vital to the steel and armaments industry, were dependent on the water and hydroelectric power supplied by a series of massive dams. If Royal Air Force (RAF) bombers could breach the dams, the consequent floods would put the factories out of action. In a single mission, the same destructive result could be achieved that otherwise would have taken 3,000 bombers two weeks of bombing the factories directly. So vital was this area to the German war effort that RAF planners had considered it as a prime target before the war broke out in 1939. Operation Chastise was about to make these tentative plans a reality. Secondary aims of the operation were to deal a blow to German civilian morale and show both the British public and Britain's allies Russia and the United States that something was being done to take the war to Germany.

Five dams were targeted, but three were a priority: Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe. A second group, depending on the success against the first group, were Lister, Ennepe, and Diemel. The RAF knew that Möhne had air defences, and it was likely the others had, too. Möhne and Eder were concrete and, designed to withstand the massive pressure of water, immensely strong structures but relatively slim targets when seen from the air. Möhne, the primary target since a breach would directly flood the factories below (not the case with Eder), was the longest dam in Europe at 120 ft high (36.6 m), 25 ft thick (7.6 m) at the top, and 112 ft (34.1 m) thick at the base. The Möhne reservoir contained 140 million tons of water (Eder had 200 million). These dams were protected by two rows of anti-torpedo nets. Eder, much further to the east, was the second choice because it was concrete, although there were no military targets in the valley below. Sorpe was strategically more important than Eder, but because it was made of largely compacted earth, the effect of bombing was anticipated to be less. The destruction of these dams and others would require a completely new kind of bomb.

The Bouncing Bomb

The new bomb was invented by Dr. Barnes Wallis (1887-1979), who had previously worked as an aircraft designer; one of his creations was the Wellington bomber, another was the R100 airship. Wallis firmly believed that "it is the engineers of this country who are going to win this war" (Dildy, 13).

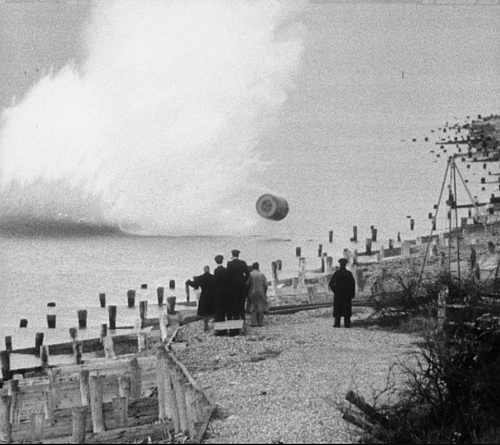

The required bomb had to reach right up against the dam wall but detonate below the surface to have sufficient destructive power. Wallis spent several years and countless hours on scale models. His solution was Upkeep, which weighed 9,250 lb (4,200 kg) and is better described as a mine or depth charge since Wallis designed it to detonate 30 feet (90.1 m) under the surface. Upkeep, packed with over 6,000 lb (2,720 kg) of Torpex underwater explosive, was shaped like a barrel (60 in / 1.52 m long) and was to be released spinning (in reverse direction) from the bomber. The barrel would then strike the surface of the reservoir and bounce along until it reached the dam. The bomb then sank and only detonated when it reached a certain depth thanks to a hydrostatic pistol firing the explosives. If the hydrostatic mechanism failed, the bomb was timed to explode anyway 90 seconds after release.

For the bomb to bounce correctly, it had to be dropped at a precise height of 60 feet (18.3 m) from the reservoir's surface, and the plane had to be at a flying speed of around 240 mph (386 km/h). Tests using real aircraft demonstrated that if dropped from too great a height, the bomb would simply shatter on impact, but dropped too low, it would either not reach the dam or harmlessly bounce over the dam wall. The bomb, since it needed to bounce precisely three times to reduce its velocity, also had to drop a specific distance from the dams, too close and it would strike the wall and ricochet off, too far and it would not reach, would veer off to the left, or would bounce over the dam. The bomb also had to sink below the water at the very centre of the dam wall and be dropped when the plane was absolutely level. Getting all these factors right, and doing so at night and under enemy fire, would need a great deal of practice by expert crews.

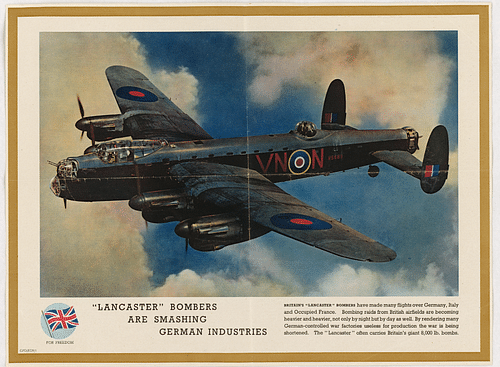

The Lancaster

By the spring of 1943, the Lancaster bomber had become the RAF's new star. It was bigger and able to fly further and with a heavier bomb load than any of its predecessors. The four-engine bomber had a length of 69.5 ft (21.18 m) and a wingspan of 102 ft (31.09 m). Top speed was 287 mph (462 km/h) and its range was up to 2,530 miles (4,072 km). The Lancasters selected for Operation Chastise had already seen some service to ensure they had no factory problems.

The Lancasters were adapted for their mission in several important ways. The bomb doors were removed to allow for a special suspension unit to cradle a single Upkeep. The cradle had an electric motor to spin the bomb to the necessary 500 rotations per minute. The dorsal turret with its machine guns was removed leaving only the nose and tail gun for defence. The dorsal gunner took up position in the nose instead (a job usually performed by the bomb-aimer). The latest VHF radios were installed so that the squadron leader could better communicate with and direct his squadron. The navigator had a restricted view when flying low, and so the bomb-aimer was expected to help out for Chastise. Accordingly, the latter's Perspex nose dome was enlarged. Pilots had markings on their windscreens to help line up the target. The usual bombsight was replaced with a simple handheld device made of wood and shaped like the letter Y. Known as the Dann bombsight, it was meant to be lined up with towers at each end of the dams, and it let the bomber know when to release at the correct distance from the dam, that is, between 400 and 450 yards (365-411 m).

To help the crews know they were at the correct height to drop their bombs, and in addition to a specially adapted altimeter for the pilot, the Lancasters were fitted with two Aldis lamps fixed to the underside of the plane and angled to create a near merger of the beams precisely 60 feet below the plane, just a bit to starboard so that the navigator could see the beams form a figure of eight on the reservoir's surface. The obvious problem with this light device, known as a ‘spotlight altimeter calibrator', was that, despite the bulbs being shielded, it made the Lancaster more visible to the enemy.

No. 617 Squadron

A special squadron was officially formed on 17 March for Chastise, which was No. 617 Squadron based at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. The leader of the highly experienced 22 crews was Wing Commander Guy Gibson (1918-1944). Gibson was only 25 but had already flown over 100 missions, and received both the Distinguished Service Order (DOS) and the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). As normal, each Lancaster had a crew of seven men: the pilot, flight engineer, navigator, wireless operator, bomb-aimer, mid-gunner (relocated to the nose, as noted), and the rear gunner. No. 617 Squadron – aviators, ground crew, and support staff – were all handpicked men, the best and most experienced available. The flight crews were all volunteers. The squadron included not only British fliers but also 29 Canadians, 12 Australians, two New Zealanders, and one American.

The crews began to train from 31 March 1943. They practised low-level navigation, low-flying over water, and dropping Upkeep off Reculver beach on the Kent coast and over lakes and countryside in various other locations across Britain. To keep the mission top secret, the Air Ministry conducted a misinformation campaign that these planes were to be used for dropping mines at sea. One Lancaster crew was deemed insufficient in skill, reducing the squadron to 19. The bomb was still being trialled as well as the crews when it was decided to dispense with Upkeep's wooden casing. It was now that the precise speed, direction, and dropping heights were calculated. By May, the crews were dropping live bombs into the sea, and a final full 'dress rehearsal' was conducted on 14 May. The men were ready and raring to go.

The Mission

The squadron took off at 9.10 p.m. on 16 May 1943. There was a good moon, and the reservoirs were at their highest levels. The 19 Lancasters approached the Ruhr in three waves. The first wave of nine planes, led by Gibson, headed for Möhne (codename Target X) and Eder (Target Y). They would all attack X before moving on to Y. The second wave of five planes headed for Sorpe (Target Z). The third wave of the remaining five Lancasters was to act as a reserve for the other two waves, and if not required, they would attack a secondary group of dams.

Möhne

The first wave lost one plane en route after it hit an electricity pylon. The remaining eight planes assembled and then lined up for their bombing run against the Möhne dam. Gibson noted:

In that light it looked squat and heavy and unconquerable; it looked grey and solid in the moonlight; as though it were part of the countryside itself and just as immovable. A structure like a battleship was showering out flak all along its length.

(Spick, 55)

Gibson went in first under fire from six flak units, the front gunner of the Lancaster giving return fire. The bomb was dropped, bounced along as intended, and hit the dam, but with no effect. Gibson noted, "The gunners had seen us coming. They could see us coming with our spotlights on for over two miles away" (Spick, 59). The second Lancaster was hit and crashed, its bomb bounced over the dam and destroyed the pumping station. One German gunner, Corporal Karl Schütte, described his view of the approaching Lancaster: "It came roaring at us out of the moonlight like a monster, as if it wanted to ram us on the tower" (Dildy, 44). For the third run, Gibson returned and flew slightly ahead to take some of the flak from the bomb-carrying Lancaster. The plan did not work, and the third Lancaster was hit. The third bomb did detonate, but it had veered off to the western end of the still intact dam. Gibson and the third Lancaster circled about to support the fourth attack. It was fourth time lucky: the bomb bounced along and detonated against the dam wall. At first, it seemed the dam would hold, but it began to crumble just as the bomb from the fifth Lancaster also struck the dam perfectly. A tidal wave of water crashed through the 250-ft (76 m) gap in the dam wall and down into the valley below. While two Lancasters set off back home, Gibson led the remainder on to Eder.

Eder

Fortunately for the bombers, the Germans had not established anti-aircraft defences at Eder, perhaps believing that the surrounding mountains were protection enough against air attack. The German command had been right since two Lancasters now made five attempts in all and on none could they drop their load at the required height, speed, and direction. On the sixth run at the dam, the bouncing bomb exploded against the concrete wall, but damage was minimal. A seventh run went awry when the bomb bounced off the dam and may have damaged the Lancaster that had just dropped it – this plane crashed on the way home, perhaps as a result of the damage. With only one bomb left, the final Lancaster's first run was aborted, but the second was successful; the dam was breached, and another terrible tidal wave was created.

Sorpe

Of the five planes destined for Sorpe, one flew too low over the sea and lost its bomb, another crashed after hitting an electricity pylon, and a third was obliged to turn for home after sustaining flak damage to the radio. A fourth Lancaster was shot down in Germany. The last remaining plane pressed on and made no fewer than nine runs at the Sorpe dam. The bomb was dropped on the tenth run but did no real damage to the dam wall except to that part above water.

The reserve third wave of five Lancasters had already lost two of its number to flak, and one had to return to base because of a mechanical failure. One Lancaster headed for Sorpe dropped its bomb and hit the dam, but to no effect. Bomber Command had known all along that Upkeep would likely not work against the earth wall, and so it proved true. The final Lancaster of the third group headed for the Ennepe Dam. In the confused landscape caused by the flooding from the two breached dams, the Lancaster mistook its target and bombed the Bever Dam, but with no damage resulting (Dildy, 62). This mistake was kept secret by the Air Ministry. All planes now returned home, and with flack guns and enemy fighters on the prowl, not everyone would make it back.

Assessment

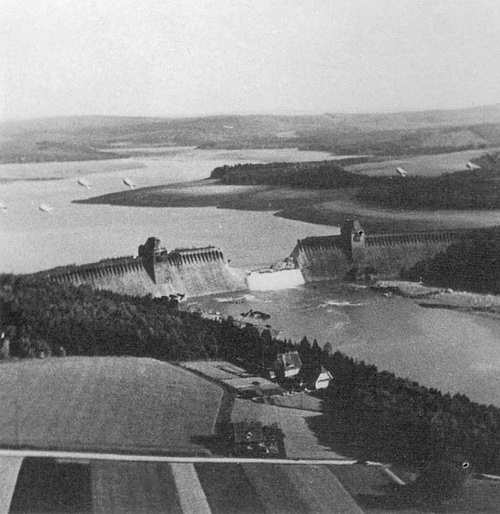

Both the Eder and Möhne dams were breached; Sorpe and Ennerpe were damaged. The mission was considered a success, and the 'Dambusters' were awarded 34 medals. The British press, amply supplied with photographs of the aftermath taken by reconnaissance flights, made the story into a great victory in taking the war to Germany. The cost was high. Eight of the 19 Lancasters did not return home, 53 men were killed, and three who were shot down became prisoners of war (Morris, 170).

Back in Germany, the tidal wave from the breached Möhne dam spread across the valley below for 50 miles (80 km) flooding over 125 factories, destroying over 1,000 homes, wrecking two hydro-electric plants and damaging seven others, flooding several coal mines, and sweeping away nearly 50 bridges. More than 1,300 civilians died in the floods, many of whom had been sheltering in cellars because of the air-raid warnings. Amongst the victims were nearly 500 Ukrainian women, conscripted labourers. Thousands of livestock drowned and vast areas of land were made unsuitable for farming for the rest of the war. The disaster was known as the Möhnekatastrophe. The breach of the Eder dam disabled four power stations, destroyed 14 bridges, and killed 47 people.

Collectively, it was the heaviest loss of life from a single RAF raid up to that point in the war. The loss of water had a knock-on effect on the functioning of factories, coal mines, and firefighting capabilities elsewhere. In addition, the German state was now obliged to spend a great deal of resources to protect dams with air defences. In short, it is "absurd to suppose that Germany could have suffered such devastation without significant cost to its war effort" (Hastings, 286).

For the British, it was certainly a disappointment that the Dambusters' damage was largely repaired in just a few months. Crucially, many of the armaments factories were left unscathed and production continued to rise in the long term. Inexplicably, Bomber Command did not follow up with raids during repair work on the dams, a relatively easy target for standard incendiary bombs.

There were less tangible but equally important successes of the mission. British prowess in planning and execution of wartime operations was demonstrated, something that had been somewhat lacking thus far in the war. Churchill received a boost in his relationship with vital partners like the United States, Canada, and Russia. The operation was milked for its propaganda value, with Gibson being sent off on a lecture tour of North America.

Other successes of Chastise include the confirmation of the advantages of precision low-flying bombing on specific targets by highly trained and handpicked crews, something Bomber Command would pursue with success for the rest of the war, alongside its more indiscriminate tactic of area bombing over large areas using a large number of bombers. The use of VHF was also a great breakthrough and led to all missions having a lead bomber, the 'Master Bomber', who could communicate vital information to those bombers which followed. No. 617 Squadron, led by Squadron Leader George Holden, was used in other missions with specific strategic targets throughout the war and ended the conflict as the most accurate heavy bomber squadron of all.

For Operation Chastise, Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross medal. Wallis was knighted in 1968. Both men became national heroes. In more modern times, Chastise has been reassessed for its impact on civilians, not least because the deliberate bombing of such targets as dams with obvious fatal consequences for civilians is today classified as a war crime in the Protocols to the Geneva Convention.