Operation Gomorrah (aka the Battle of Hamburg or Hamburg Air Offensive) was a sustained area bombing campaign of the German port of Hamburg in four night attacks by the Royal Air Force and two daytime attacks by the United States Air Force in July and August 1943. Over 3,000 bombers created a firestorm, which resulted in 46,000 civilian deaths, one of the worst civilian disasters of the Second World War (1939-45).

Area Bombing

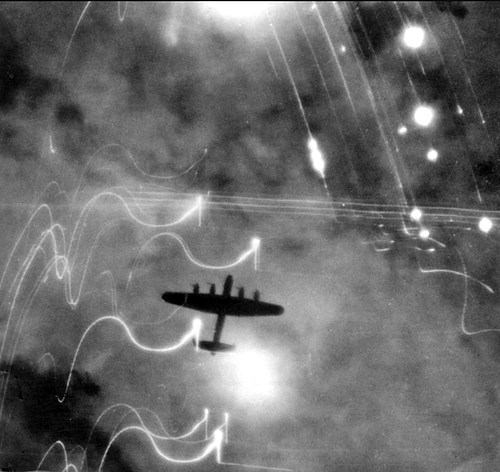

The Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command from February 1942 to the end of the Second World War was Arthur Harris (1892-1984), and he had very definite ideas on the best and quickest way to win the conflict. Harris, and it should be noted others in high command, firmly believed that extensive and sustained area bombing (aka carpet bombing) – bombing a large area simultaneously – conducted against Germany's most important cities would bring about a surrender. From his own experience of the London Blitz, when the Luftwaffe (German airforce) had mercilessly bombed the capital in 1940 and 1941, Harris believed that the dropping of incendiary bombs rather than using explosive bombs alone could best wreck a city. A very large force of bombers would be required. Previous operations had shown that daytime bombing brought too heavy losses to the bombers from attacks by fighter planes and anti-aircraft guns. Cloud cover was another impediment to accurate bombing. Switching to night-time bombing had become necessary since the bombers were then much more difficult to find, although this also made bombing even more inaccurate than it already was. Hitting strategic but relatively small targets like armaments factories or U-boat bases proved unsuccessful with the technology available at the time. Post-raid reconnaissance revealed that only one in three aircraft dropped its bombs within 5 miles (8 km) of the intended target. The answer seemed to be area bombing. If 1,000 bombers or more – four or five times the usual number used by either side in a single raid – could reach a city and repeatedly drop bombs over a wide area, the results would be devastating.

What was not considered by everyone was that the effect on morale of area bombing cities would be questionable. As the Blitz had shown, civilian morale could be very resilient indeed. Perhaps more importantly, even if civilians could be demoralised in Nazi Germany, they were not living in a democracy but in a dictatorship where dissent could very quickly end in imprisonment or death. In short, a demoralised civilian population did not mean that a regime change would follow. A better argument regarding morale would be to state the benefit to British civilian morale (and to a lesser extent that of Britain's allies) of an air campaign that showed the armed forces were returning in kind the horrors the British civilians themselves had been experiencing, a much more important influence on a government in a democracy.

Promoted to Air Chief Marshal, 'Bomber' Harris, as he was known, later became something of a scapegoat for the area bombing campaign as others wished to disassociate themselves from a strategy that killed tens of thousands of civilians. Harris did not conduct the air war in Europe on his own. It is important to note that Prime Minister Winston Churchill supported Harris. At the time, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) was considering reducing the aircraft supplied to Britain, and so a show of the usefulness of air raids might stop these cuts. Finally, there was another advantage to large-scale area bombing besides destroying material and morale, one which is often forgotten. Large bomber forces suffered fewer casualties proportionally than smaller forces did. As Harris noted, "One of the main ideas of sending over the bigger attack was to overwhelm the defences, and that's exactly what occurred" (Holmes, 299).

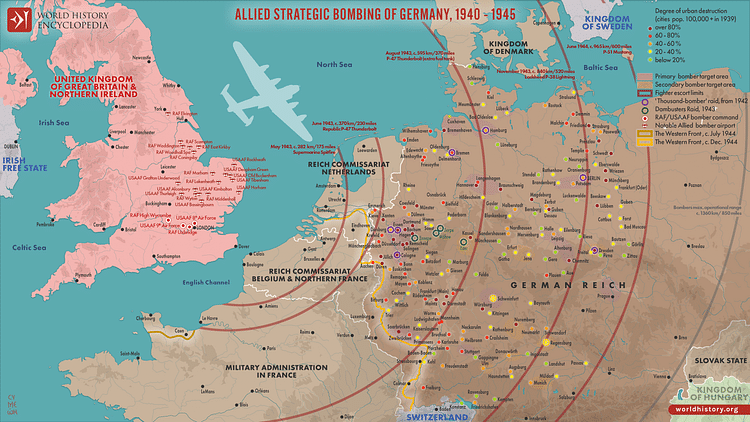

The first large-scale bombing raids on Lübeck and Rostock were carried out with success in the spring of 1942 and led to Harris' big test: Cologne. On the night of 30 May 1942, Harris amassed a force of over 1,000 bombers, which, by necessity, included training units, and directed them to Cologne. Actually, Harris' preferred target that night was Hamburg, but cloud cover led to a switch to Cologne. The people of Hamburg were unknowingly spared, but their time would come one year later.

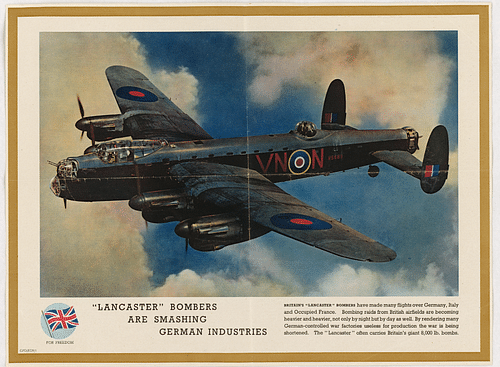

The RAF's best bomber, but still relatively few in number at this stage, was the four-engine Lancaster bomber, capable of carrying a bomb load of up to 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg). The bombers smashed Cologne for the loss of 40 aircraft. Deemed a success, more bombers were ordered and Harris' area bombing strategy was pursued further, although none would ever have the same surprise impact as Cologne.

The RAF rolled out better equipment and the new Pathfinder (PFF) squadrons, which dropped Target Indicators (TIs) so that pursuing Lancaster bombers could sight the target better. Massive thousand-bomber raids were made on Essen on 1 June and Bremen on 25 June 1942. Indifferent results and the weight of resources needed to operate such large attacks meant that future operations were inevitably reduced in scale. From March to July 1943, the RAF concentrated on more specific targets in the Battle of the Ruhr, that is bombing the armaments-related industries in the Ruhr basin. The most famous attack was on the Ruhr dams in Operation Chastise, the 'Dambuster' raid. However, by the end of July 1943, Harris once again turned to cities. This time, it was Hamburg's turn to face a bombing nightmare in an operation codenamed "Gomorrah" after the biblical city destroyed by God for the wickedness of its residents. The codename is highly suggestive of the RAF's ambition for Hamburg: total destruction.

Gomorrah: The Onslaught

Hamburg was Germany's second-largest city, was Europe's largest port, and had important dock works which had built the mighty battleship Bismarck amongst many other ships. There were, too, large and active U-boat yards and aircraft factories. Many of the city's residents, of course, worked in these shipyards and factories across the city. There was another reason Hamburg made a good target; being close to the coast, it was easier to find than an inland city, and it was well marked out by the River Elbe running right through it. For all of these reasons, Hamburg had already been attacked in January 1943, but the raid of around 150 bombers was not a success, the bomb drops being too scattered. Operation Gomorrah would rectify this failure.

The RAF assembled an unprecedented 3,000 bombers to attack Hamburg on four separate nights: 24, 27, 29 July, and 2 August. According to Albert Speer (1905-1981), the German Minister of Armaments, the RAF forces on each night numbered 791, 787, 777, and 750 bombers. A little under half of the force was made up of Lancasters. These attacks were intended to have all of the bombers fly over their target in an unprecedented short time of 90 minutes. On top of this onslaught, the Eighth Air Force of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), which was now based in Britain, conducted lighter daytime raids on 25 and 26 July using 235 B-17F bombers. Unlike the RAF, the USAAF's targets were specific: the Klockner aero-engine factory and the Blohm & Voss shipyards. Gomorrah's angels of death would drop some 8,600 tons of bombs on the city in six waves.

In the attacks, the RAF used for the first time Window (US name: Chaff), essentially foil-covered strips dropped in their thousands to create a cloud of metal that caused havoc with the German radar defences and the gun-aiming devices of anti-aircraft weapons. The defenders saw only a blizzard of white dots on their screens and could not differentiate the planes from the foil strips. The bombers dropped their loads across the city, the area of devastation spreading as each successive squadron dropped a fraction before the previous bombers, an undesirable phenomenon known as 'creepback' which resulted in some bombs falling 7 miles (11 km) from the bombing centre. The aircraft loss rate varied from 1.5 to 6% depending on the particular night. In total, 86 bombers were lost. The official RAF damage report blankly stated: "The city of Hamburg is now in ruins. The general destruction is on a scale never before seen in a town or city of this size" (Spick, 37).

The Firestorm

The bombers on the second night used a combination of high explosive bombs and incendiary bombs, which created a massive firestorm, literally a man-made hurricane of fire. The phenomenon was further fuelled by hot and windy weather. In a firestorm, the fires, desperate for oxygen, pull in air from elsewhere, a phenomenon that creates a wind of fire that quickly spreads the flames and burning debris over a wider and wider area. Eventually, masses of fires merge to create one huge storm with hurricane-speed winds. Temperatures soared to 800 degrees Celsius in some areas. The area affected measured 8.5 square miles (22 sq. km) as the fires spread unchecked since the firefighting service had no means to combat the terrific temperatures or the speed of the fire which spread across the entire city in just 60 minutes. Thousands were asphyxiated by the superheated air.

A Hamburg journalist, Ben Witter, gives the following eyewitness account of the Hamburg raid:

…I saw people running away, they were burning like torches, and our car was jolting over dead people. Because of the heat the bodies had shrunk and we thought they were children, but they were adults. This attack was concentrated on an area where many working men lived but which also contained a lot of factories. The whole area was crossed by canals and most of the people tried to leap down into them but the water was on fire. (Holmes, 303)

Speer gives the following summary of the tragedy:

The first attacks put the water supply pipes out of action, so that in the subsequent bombings the fire department had no way of fighting the fires. Huge conflagrations created cyclone-like firestorms; the asphalt of the streets began to blaze; people were suffocated in their cellars or burned to death in the streets. (389)

Death Toll & Damage

The casualties were enormous. 800 military personnel were killed in the attack. Around 46,000 civilians died; of these around 22,000 were women, and 5,000 were children. To give some perspective on the death toll, around 60,500 civilians were killed in Germany's bombing of Britain in the course of the entire war.

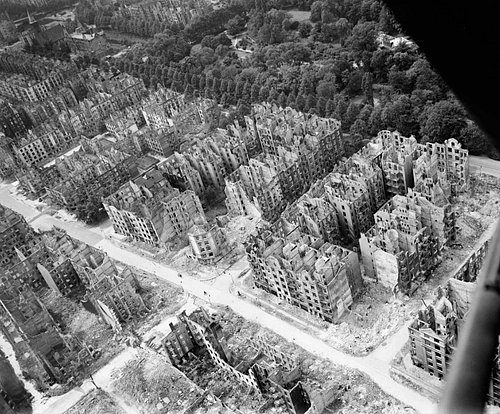

Half of the city of Hamburg was destroyed, and two-thirds of the survivors, one million people, had to be evacuated. The carpet bombing wiped out 580 factories involved in the armaments industry. The U-boat yards, in contrast, did not receive significant damage, and no bombs at all ever hit the Klockner aero-engine plant. The USAAF bombers had been greatly impeded by the vast amount of smoke billowing over the entire city. For this reason, one group of B-17Fs selected two other targets: the Howaldtswerke shipyard (slightly damaged) and the Neuhof power station (destroyed). It was clearly a mistake to send the RAF area bombers in before the USAAF precision bombers, although the city's defenders were themselves sending up smoke from smoke pots to obscure the skies. In addition to the factory damage, the elimination of a large number of workers greatly affected the production recovery. It is, for example, estimated that the lack of available workers after the raid meant that 27 U-boats were not built that otherwise would have been. The U-boat yards never fully recovered but did regain about 80% capability within five months.

Speer noted:

The devastation of this series of air raids could be compared only with the effects of a major earthquake…a series of attacks of this sort, extended to six more major cities, would bring Germany's armaments to a total halt…Fortunately for us, a series of Hamburg-type raids was not repeated on such a scale against other cities. Thus the enemy once again allowed us to adjust ourselves to his strategy.

(389)

Aftermath

In Britain, Operation Gomorrah was deemed a success. The destruction imposed on the enemy came at the cost of 21 USAAF and 87 RAF bombers lost. The effect on morale was difficult to measure, but it is perhaps significant that Hitler did not visit the city and ordered a news blackout on the Hamburg raids.

The use of Window in the Hamburg air offensive, a device the Germans had themselves but not yet used, meant that the German airforce was obliged to rethink its strategy of air defence. Previously the Kammhuber Line and Raumnachtjagd systems meant that fighter planes were distributed in "boxes" in an imaginary grid across Northern Europe, the planes circled within these "boxes" at night until given the direction of enemy aircraft by radar operators. The problem with the Hamburg raid was that many fighters were not given permission to leave their "boxes". Now new additional tactics involved the Wilde Sau ('Wild Boar') strategy, which permitted fighters to fly freely above cities and attack enemy bombers at will. To ensure the fighters were not hit by their own anti-aircraft guns, the fighters patrolled above a pre-arranged altitude. With Allied bombers attacked from above and so made visible against the fires of the targets they were bombing, Wilde Sau proved successful.

Hamburg took many years to recover from Operation Gomorrah. One RAF pilot, Flight Lieutenant Jimmy Davidson, who had been surprised by the orders to repeatedly bomb the city, visited again in July 1945, this time on the ground. Davidson noted:

The desolation appeared complete – acre upon acre of lifeless ruins – and I was more than glad that no one could point the finger and say where my bombs had fallen. It was one thing to bomb in the heat of battle and another to see one's contribution against the background of a defeated enemy.

(Neillands, 240-1)

Bomber Command continued with its strategy of area bombing, but a lack of resources meant this could not be done immediately, as Speer had feared. There would be no immediate repeat of Gomorrah. The next major bombing target was the German capital from November 1943 until March 1944, a sustained campaign that became known as the Berlin Air Offensive (aka Bombing of Berlin).

The strategy of area bombing remained a contentious one, with many leaders on both sides pointing out that precision bombing was still extremely difficult as the enemy constantly made advances in its defence technology. In the end, there was a mix of area and precision bombing by both the RAF and USAAF in what became known as the Combined Bomber Offensive. Further, the air war continued to be the only way to take the war directly to Germany's doorstep in the absence of a ground invasion that would not come until D-Day in June 1944. The possibility for great bomber protection given by the USAAF's close bomber formation-flying and the arrival in great numbers of the P-51 Mustang, the new long-range US fighter, did mean that bombers were better protected than ever and that daylight precision bombing could be favoured in Europe through 1944. In February 1945, the RAF's thousand-bomber raids of WWII continued with another infamous victim: Dresden.

Although Harris remained convinced that bombing cities would lead to Germany's surrender, the strategy could be seen as going against the Pointblank Directive (June 1942), where the Allied High Command had agreed that bombing targets of military and strategic value was the priority over civilian targets in preparation for the forthcoming land operations in Europe (although the directive was ambiguous since it did include lowering civilian morale as a legitimate objective). The RAF's heavy losses, the lack of evidence that German civilian morale was being broken, and the concern over high civilian casualties all contributed to seriously discredit the idea of area bombing both in the minds of the military decision-makers and the general public, at least in Europe. Certainly, this was the case as the war moved into a new and final phase focussing on land operations.

The unimaginable horrors of area bombing were witnessed again from May to July 1945 when, in order to avoid just such a ground offensive as the Normandy landings, the civilians of almost all Japanese cities faced massive bombing raids, a campaign of terror which culminated in the total devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki using atomic bombs.