The Oradour-sur-Glane massacre in southwest France was the murder on 10 June 1944 of 643 civilian men, women, and children by the Waffen SS during the Second World War (1939-45). The massacre and the razing to the ground of the village was carried out in retaliation for activities of the French Resistance. Today, the site is a memorial to the atrocity.

Located around 20 kilometres north-west of Limoges in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of France, Oradour-sur-Glane was a quiet village of around 1,600 inhabitants until the day of the massacre. That fateful day in June 1944, members of the Waffen SS Das Reich, an elite German unit originally based near the town of Montauban, further south, rounded up the population present in the village at the time and murdered them. In 1947, work began on rebuilding the new village of Oradour on the outskirts of the original site, so that the martyred village would become a place of remembrance for the innocent victims who were cruelly killed there.

The Waffen SS Das Reich Division in France

The Waffen SS (armed SS) acted as the Reich's ‘second’ army. Initially, its members were recruited by quota from the ranks of the Schutzstaffel (commonly called SS), then, over time, on a voluntary basis or by reassignment of soldiers from the Wehrmacht (the armed forces of Nazi Germany), and from 1943, by forced drafting of Soviet prisoners and members of the population of occupied territories such as Alsace and Moselle, in France.

The history of the SS Waffen Das Reich Panzer division is complex and dynamic, as it was moved several times according to the progress of the German army, and was deployed in various occupied territories. The 2nd SS Division (its original name) had been deployed during the offensive in the Netherlands in 1940 and then moved south through France with the advancing German army. It was involved with the surveillance of the demarcation line at the start of the occupation of the country. After its withdrawal from France, the division underwent major changes and eventually regrouped in Vesoul, in occupied France, under the name Waffen SS Das Reich. The exact number of soldiers in the division at that time is not known, but estimates give an approximate figure of around 19,000 troops.

The division was then sent to the Balkans in 1941, where it took part in a murderous campaign that resulted in the death of countless civilians. It was then positioned on the Eastern Front and took part in many battles until the Soviet Union advanced westwards. While in Central Europe, the Das Reich division took part in many brutal actions in which the civilian population was severely punished if those suspected of resistance activities were not apprehended.

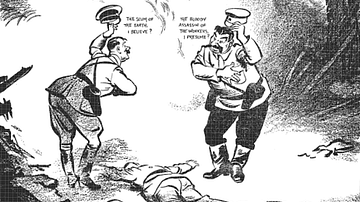

It was not immoral to kill “subhumans”. Nazi ideology, made up of expansionism, anti-Bolshevism, and racism, required it… this criminality now so ordinary, bound the troops together in the most difficult phases of the combat against the Soviet army. The cohesion of the Army of the East was maintained by a mixture of iron discipline in combat and extreme tolerance with regards to acts of barbarity committed against the enemy.

(Fouché, 27)

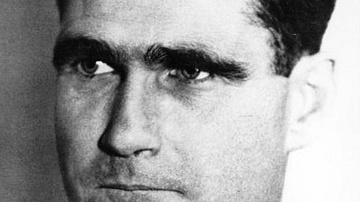

The new recruits who swelled the ranks of the division as time went on were quick into action, burning villages and executing people suspected of helping the local resistance. They quickly got used to blood and death. During these operations, they did not target the resistance as such, but concentrated on carrying out reprisals on the populations of the towns and villages in the region. The Waffen SS soldiers present at Oradour on 10 June 1944 had been active on the Eastern Front. In 1944, as an invasion of the Continent loomed on the horizon, the Das Reich division was regrouped near Bordeaux, France, under the orders of SS Brigadeführer Heinz Lammerding (1905-1971) and what little remained of its troops left behind on the Eastern Front were repatriated, including a number of ‘Malgré-nous’ (against our will), young men from annexed Alsace and Moselle who had been drafted by force, as well as men recruited from outside the Reich's borders.

By late May 1944, the German high command was clearly concerned with the activities of the local resistance in France, the Maquis, as evidenced in the following official communication:

Strong rise in Resistance movement activity in Southern France, particularly in the areas south of Clermont-Ferrand and Limoges…Concentrations of armed groups near Tulle… Great terrorist activity in the department of Corrèze. Frequent attacks on trains, unreliable towns… thefts of vehicles and fuel… Powerful counter-attack being prepared with necessary forces and air support. (ibid, 42)

Even the local authorities reported on this intensification of resistance activities, which resulted in a corresponding intensification in repression: arrests of former army commanders, occupation of villages, rapes, and pillaging. The German high command really needed to tackle the potential threats behind the coastal lines as the possibility of an invasion was getting higher. Harsh measures were therefore deemed necessary. On 7 June 1944, the Das Reich division was ordered to move in and clear the areas of resistance because after the news of the Normandy landings on 6 June, numerous liberation actions were being carried out throughout the area. The last straw might have been the disappearance of a German commander, SS Sturmbannführer Helmut Kämpfe (1909-44), who had taken extremely harsh measures against the population and whose vehicle was found abandoned on the side of the road. However, some historians believe that this was merely a pretext, as the commander was probably killed several kilometres away from Oradour.

In any case, on 10 June, a convoy of several German army trucks was present in the town of Saint-Junien. After a meeting between SS officers, the decision was taken to go to Oradour to demand 40 hostages in reprisal for the capture of Kämpfe. At around 1.30pm, two Waffen SS columns left Saint-Junien, the larger one heading east. A German soldier noted:

We were ordered to move out, the entire company, not knowing what direction we would take. But they repeated we were to look for the chief of the third battalion, who had been captured under circumstances I was not aware of. It was on arriving near a village that I saw a sign saying: Oradour-sur-Glane. (ibid, 64)

The company was then divided into several groups, about 200 SS Waffen soldiers in all, who suddenly made their appearance in the small village.

The Village of Oradour-sur-Glane

At the time, Oradour-sur-Glane was a typical southern village with a bridge spanning a river where the locals went fishing and near which, in summer, parents would set up their picnic blankets while the children enjoyed a swim. It could have been described as the ideal French village, set in a peaceful region that inspired the famous French painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875) who painted some of his works in the area.

From 1939, the village, a socialist stronghold, had seen successive waves of immigration. People came from Fascist Spain (whose refugees quickly got involved in the local groups of foreign workers) and from occupied Alsace, Moselle and Lorraine in 1940.

Until that point, Oradour had not suffered too much from the horrors of war. Its rural economy, which had previously been on the verge of disaster due to the fact that the local youth was attracted to a better life in the cities, was given a new lease of life thanks to the inhabitants of Limoges. Those living in this important city, a mere 22 km away, were suffering from rationing and shortages, and therefore, used to travel to Oradour by tramway to stock up on foodstuffs of all kinds, both legal and illegal. The black market in Oradour was flourishing.

At the time, the town of Oradour, boasted four grocery stores, three butcher shops, one of them also a delicatessen, two bakeries, one pastry shop-café, one wine merchant, about ten cafés, five inns with restaurants, three hotels, dry-goods and haberdashery stores, a collection of stores where people learned to adapt to the situation. (ibid, 93)

The village of Oradour was clearly a much-visited place, and it was too exposed to host any form of resistance. In short, the village was leading a perfectly normal life in 1944 France, with its share of clandestine activity such as gatherings and film screenings for the local youth.

Day of the Massacre

On 10 June, at around 1.45pm, some young people who were waiting for the shops to open saw a column of vehicles arrive from the other side of the bridge over the river Glane. Little did they know that the entire area had already been surrounded, with some soldiers taking up positions with their machine guns pointing at the village. The trucks that made their way through the town represented only a fraction of the German troops present that day. Calmly, almost mechanically, the soldiers carried out their orders.

One group of soldiers was tasked with rounding up the inhabitants (without exception) and holding them at gunpoint on the village fairground, while others were instructed to stand guard on the outskirts, watching over the roads leading into the town, not so much to prevent access, but rather to prevent anyone leaving (although some individuals were indeed prevented from entering the town and told not to go any further if they wished to stay alive).

Houses were searched. The four schools were entered. Children and teachers were herded to the fairground (only one child managed to escape). Even the sick were forced to leave their homes. Those who could not or would not go to the fairground were shot on the spot. Some tried to escape, and a few succeeded, but many were caught and taken in the roundup. Most of those who managed to survive, whether they went into hiding or fled, had either already experienced immense fear at one point or another in their lives, or simply had genuinely valid grounds for refusing to obey SS orders. The roundup had been extremely violent, doors had been kicked-in, windows smashed, gunshots had been fired, and people had died. After everyone was gathered on the fairground, a commander asked the mayor, Paul Désourteaux, to select 50 hostages, which he refused to do and offered himself and his family instead. Incensed by his lack of cooperation, the Germans started to form groups of 40 to 50 people: the women and children were made to leave and were taken to the church amid the heart-breaking cries that shattered the peace and quiet of the village.

After a while, the men were divided and taken to different enclosed areas far from each other, in barns, workshops, garages, and storehouses. In one of the barns, as soon as the men were assembled, they were machine-gunned, those who had not succumbed straight away were shot dead at close range. Then, after filling the barn with hay, the Germans set it on fire. Each time, in each location, the same actions were repeated, the hapless hostages unaware of the fate awaiting them. While this was happening, some soldiers were roaming the streets, ransacking and pillaging houses and shops, and eventually setting them on fire. The whole village was systematically set ablaze. Those who had managed to hide were soon forced to escape for fear of suffocating; for many this act turned out to be their last as they were gunned down.

All of the women and all of the children had been assembled in the church. After a long wait of about 90 minutes, the Germans started to leave through the main door, but two of them brought in a heavy box which, after a while, started releasing a stinging smoke that would soon fill up the whole building. As the women started screaming and shouting, shots were fired from outside through the stained glass windows and the main door. Grenades were then thrown in. As the church had not been destroyed by the explosion of the device in the box, some soldiers walked back in and started a fire. Some victims tried to seek refuge in the sacristy or in the confessionals. Eventually, the roof collapsed. Two women, one with a baby, managed to escape the carnage, but only one would survive her injuries. One SS soldier recalls:

We were made to gather in the street opposite the church to watch it being destroyed. The battalion commander had us stand to attention. We could still hear screams inside. Warrant Officer Gnug blew up the church.

(Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour, 86)

Once the massacre was over, one group of SS troops remained in the village, setting up camp in a shop that had previously been pillaged. The empty bottles later found on the spot tell of an evening of great merriment. Their mission had been accomplished. In the meantime, some survivors lay in hiding while others, under the cover of darkness managed to escape.

On 11 June, some soldiers returned to the scene of the massacre to bury the bodies, some of which were totally dismembered, in mass graves in order to prevent anyone from identifying the dead. In addition to the fact that they had perpetrated a heinous crime, some of the soldiers allegedly committed horrendous outrages on some of the bodies.

Aftermath

The list of victims took a long time to be established but in January 1947, it was finally recorded that 643 people had died during the massacre (according to the Centre de la mémoire d'Oradour). Most bodies were not identified, with only 52 being granted a nominative death certificate. All the others were recorded as 'Victims officially classified as missing', some whose names are not even known such as “Monsieur Picat’s maid”. The town hall had burnt down and all the records had disappeared, the local administrators were dead, no one was able to say precisely who had been present in the village on June 10. It was therefore also extremely difficult to determine how many people survived that day. Six people might have survived the massacre itself, one woman from the church and five men from the shooting in the barn, 19 had hid in the village and 12 tram passengers on their way to Oradour had been sent back to wherever they were coming from.

In 1953, almost 9 years after the massacre, a trial for war crimes was held in Bordeaux. 21 defendants were present: 7 Germans and 14 French (one SS officer and 13 forced conscripts). After 27 days of hearings, on 11 February, a guilty verdict was established. Two defendants received death sentences and all the others received sentences of hard labour or imprisonment. Nevertheless, on 14 April, following an amnesty law and a waiver by the French Ministry of Finance of the obligation to pay legal costs, the French nationals of Alsace and Moselle who had been involved in the massacre but who had been drafted by force into the SS were granted a total amnesty, much to the dismay of the inhabitants of Oradour.

Conclusion

As early as 1944, plans were made to rebuild Oradour on a nearby site, a little further west, on a spot with a beautiful view of the river Glane. On 10 June 1947, French President Vincent Auriol (1884-1966) laid the foundation stone for the new village. Reconstruction continued into the 1990s, with the planting of trees along the rue de 10 juin, the construction of a village hall, and the repainting of house facades.

On 28 November 1944, the Provisional Government decided to preserve the remains of the original Oradour-sur-Glane and make it a place of remembrance and self-reflection for visitors. For almost 20 years, in reaction to the 1953 amnesty decision, the National Association of Families of Martyrs chose to exclude the authorities from the commemorations of the 10 June massacre and to organise ceremonies in complete privacy.

Despite the disappearance of contemporary witnesses and the inevitable erosion of the collective memory over time, the village memorial continues to inform modern visitors of the atrocities perpetrated in occupied Europe during the Second World War. Sadly, Oradour-sur-Glane is just one of the many places that witnessed such horrors, others include Lidice in the Czech Republic and Khatyn in Belarus. Oradour is today twinned with the Greek village of Distimo in Boeotia, which endured a similar fate, in an effort to bring people together and encourage international relations in the hope that such unjustifiable acts will never happen.