Ostracism was a political process used in 5th-century BCE Athens whereby those individuals considered too powerful or dangerous to the city were exiled for 10 years by popular vote. Some of the greatest names in Greek history fell victim to the process, although, as the votes were often not personal but based on policies, many were able to resume politics after they had served the statuary 10 years away from their home city. Nevertheless, ostracism was the supreme example of the power of the ordinary people, the demos, to combat abuses of power in the Athenian democracy.

The Process

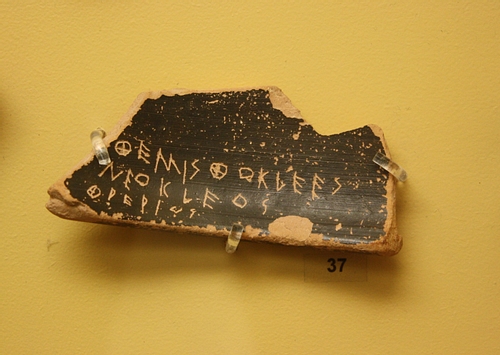

The decision whether or not to ostracise individuals was taken once each year. First, the decision to hold a vote on ostracism was presented to the popular assembly of Athens, the ekklesia, which met on the hill of Pnyx. There up to 6,000 male citizens voted to proceed or not. If agreed, a special meeting known as the ostracophoria was organised in the agora on a particular day in the eighth prytany in the year (which was divided into ten such units). The voting was supervised by the executive council of 500 (boule) and the 9 highest administrative officials, the archons (archontes). Citizens voted against a particular candidate by scratching his name on a piece of pottery, an ostrakon. Voting was done anonymously. Officials known as phylai then collected the ostraka and made sure that nobody voted twice.

For the result of an ostracism to be effective a minimum of 6,000 votes had to be cast. Then the officials announced which individual had amassed the most votes and that person was ostracised, that is in the original meaning of the term, exiled. There was no possibility of appeal against the decision. The man was given 10 days to organise his affairs and then he must leave the city and never return to the region of Attica for a period of 10 years. Interestingly, the individual did not lose their citizenship and nor was their personal property confiscated.

Abuse of the System

The exile was not a permanent disgrace as some individuals did return after their sentence was served and continued in public life. This perhaps indicates that votes were very often cast against the policies of an individual rather than them personally and that voting against one individual gave support to their rival and his policies. However, there must surely have been cases when, without any formal charges or speeches, the assembly was swayed by popularism and voted against individuals without good reason. Plutarch in his Aristides biography famously recounts the intention of one assembly member to vote against Aristides simply because he is fed up with hearing the politician constantly referred to as 'The Just'.

Another suspicious abuse is the finding of 190 ostraka in a well near the acropolis of Athens, all with the name of Themistocles scratched on them but done so by recognisably few hands. Are these, perhaps, indicators that supporters of Themistocles' rivals handed out ostraka to corrupt assembly members in order to fix the voting?

Famous (or Infamous) Exiles

Aristotle claims that the actual institution of the process was made in c. 508 BCE under Cleisthenes in order to prevent tyranny by a single individual. However, the first actual ostracism was not held until c. 487 BCE. Then, a certain Hipparchus, son of Charmus, and related to the tyrant Hippias, claimed the dubious distinction of being the first recorded exile using this method. Megacles and Callias, son of Cratius, followed in the next two years. These early exiles were probably guilty of supporting Persia and opposing the increasingly democratic government in Athens.

The cases of Xanthippus (exiled in 484 BCE) and Aristides (482 BCE) are notable as they were both given a pardon and allowed to return to Athens in 480 BCE to meet the new threat of a Persian invasion by Xerxes. Over the next decades, some of the most illustrious names in Greek history then fell victim to the process, as shown in the 12,000 ostraka which have survived from antiquity. The famous statesman Themistocles was exiled c. 471 BCE following accusations of bribery; Cimon, the great general, was suspected of being too friendly with Sparta in 461 BCE; and Thucydides (not the historian) was the victim of Pericles, who employed ostracism to handily remove his rival from the political arena in 443 BCE.

The End of Ostracism

The last recorded individual to be ostracised was the demagogue Hyperbolos c. 417 BCE. He had hoped to use the process to exile one of his two great rivals, Alcibiades or Nicias, but, joining forces, the two managed to get Hyperbolos voted out of the city instead. After that, there were no more cases, even if the process still remained legally possible until the 4th century BCE. Political rivals turned instead to the process of graphe paranomon where anyone could make a formal accusation against an individual and claim their proposals were unconstitutional. A person accused and found guilty of the charge was heavily fined and, if they lost three such cases, were no longer eligible to participate in politics.

Later sources suggest that ostracism was also carried out in Argos, Megara, Miletos, and Syracuse but there is scant archaeological evidence for this. The 1st-century BCE historian Diodorus of Sicily describes a type of ostracism in the latter city where, briefly, olive leaves were used instead of pottery sherds in a similar process to ostracism known as petalismos.