The Oyo Empire flourished from the 17th to 19th century CE in what is today southwest Nigeria. The Oyo forged an empire thanks to their formidable cavalry units and so came to dominate other Yoruba peoples of the region. The Oyo Empire, with its capital at Old Oyo near the Niger River, prospered on regional trade and became a central facilitator in moving slaves from Africa's interior to the coast and waiting European sailing ships. The trade in humanity was so large that this part of Africa became known simply as the 'Slave Coast'. The Oyo eventually succumbed to the expanding Islamic states to the north, and by the mid-19th century CE, the empire had disintegrated into small rival chiefdoms.

Origins

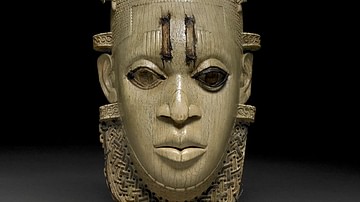

The Oyo Kingdom, as with other states of the Yoruba people in the southern coastal area of West Africa (modern Nigeria), claimed descent from an exiled king of Ife (11-15th century CE). Although archaeology has yet to discover concrete connections between the various successive states of what is today Nigeria, oral traditions, such as those in the Kingdom of Benin (13-19th century CE), located just to the east of Oyo, tell of a king of Ife who not only sent a prince to rule other areas of the region but also sent a master craftsman to spread his sculptural skills. In oral traditions, the founder of the Oyo state was one Oranmiyan (aka Oranyan), son of Oduduwa, the founder of Ife. An impressive carved granite column from Ife stands 5.5 metres (18 ft.) tall and is known as the Opa Oranmiyan or 'staff of Oranmiyan'. Oyo art in general displays a striking resemblance to that of Ife and Benin. Through this process of cultural transfer, the Oyo inherited a long cultural tradition which stretched right back the Nok Culture of ancient Nigeria (5th century BCE to 2nd century CE).

The principal settlements of the Oyo were in and around Ife, the old capital of the Ife Kingdom, Old Oyo (aka Oyo Ile or Katunga), Kusu and Igboho. From 1450 CE, the region prospered thanks to trade with such northern states as Hausaland (15-19th century CE) and, to the south, with Portuguese sailing vessels that plied the coast of West Africa. By the late 16th century CE, the Portuguese were joined by the British, French, and Dutch, eager to obtain a slice of the lucrative regional trade.

Slave Trade

The Oyo territory came to encompass a real mix of environments with portions of rainforest, dry forest, savannah, and mangrove swamp. The Oyo benefitted most from the savannah regions, which facilitated easy movement and trade contacts with neighbouring states. As with the states which prospered throughout the second millennium CE in the region, the Oyo Empire exploited local resources such as okra, yams, dates, palm oil, and fish. Iron-smelting technology permitted the production of iron tools and weapons while traded goods included kola nuts, pepper, ivory, gold and slaves. Imported goods included horses and goods from the Mediterranean which had crossed the Sahara via camel caravans and then travelled southwards across the savannah belt and down the River Niger.

By the 18th century CE half of the slaves taken from Africa came from the southern coast of West Africa, and the area controlled by the Oyo Empire, the Kingdom of Dahomey (c. 1600 - c. 1904 CE, modern Benin), and the Kingdom of Benin - the Bight of Benin - came to be widely known as simply the 'Slave Coast' (the 'Gold Coast', another lucrative trade hub, was further to the west). There were two main reasons why the slave trade centred here: firstly it was one of the most densely populated areas of Africa reachable by the Europeans, and secondly, the Oyo Empire, and to an even greater extent the Kingdom of Dahomey, provided the necessary command infrastructures to organize the movement of slaves from the interior to the coast. In return, the Oyo received European goods which they could use themselves or trade with neighbouring states. Despite an oral tradition that minimises the Oyo's involvement in the slave trade, the Oyo Empire certainly used slaves within its own state structures - many officials in the administration and military, for example, were of slave origin - much more so than in other states in the region.

Expansion

Although the Oyo did not form many large towns of note, rulers were able to forge a small empire thanks to their fearsome cavalry and archers - both a result of their commercial tentacles reaching as far north as the trans-Saharan trade routes. Consequently, the kingdom expanded to include areas of the southwest and, in the savannah to the north, it acquired territory from its neighbours the Borgu and Nupe states. The Nupe did conquer Old Oyo around 1535 CE and held onto it until the Oyo kings regained it around 1610 CE. Both the Owu in the south and Ede to the southeast became vassal states of Oyo as the empire reached its peak from the first half of the 17th century CE, eventually conquering 13 rival kingdoms.

The motivation for this territorial expansion was to gain control of the lucrative regional trade routes along which salt, gold, and slaves were transported. This was particularly true for the coastal areas which had a longstanding trade relationship with European sailing vessels. The Oyo did not have everything their own way, however, as groups like the Ijesha inhabited forested areas where the Oyo cavalry could not be used effectively and the dangerous tsetse fly was present. The same was true for the Ekiti who dwelt in the hills bordering the far northern stretch of Oyo lands. The Kingdom of Benin in the east was another formidable block to Oyo ambitions. Interestingly, the Oyo also took cultural ideas, not just land from its rivals, notably adopting the prominent ancestor worship of the Nupe into their own religious practices.

Naturally, other regional powers were also anxious to control trade routes, notably the Kingdom of Dahomey to the west. Oyo and Dahomey were at war between 1726 and 1730 CE, a conflict which the Oyo Empire eventually won. After 1730 CE, Dahomey consequently accepted the political authority of Oyo and the latter claimed some of the Dahomey coastal conquests, giving the empire its own direct access to the sea via the tributary state of Ajashe (aka Porto Novo).

Decline

The Oyo Empire might have achieved regional dominance but a much bigger power was slowly moving itself into position far to the north. The 18th century CE had already seen an expansion of the northern Islamic states who had embarked on a holy war to spread their faith. These invasions, reaching ever further south by the 19th century CE, caused severe disruption to Oyo's trade and highlighted the inherent weakness in the Oyo political setup. The Oyo king, the Alafin, had already been in conflict with both the state's ruling council of elders, the Oyo Mesi, and the military leader, the bashorun (who also led the Oyo Mesi). There was constant friction throughout the 18th century CE between those who wanted peaceful trade and those who favoured military expansion. This situation and the loose control of vassal states meant that the Oyo Empire was really a house of cards awaiting the winds of change.

The storm duly came in the 1820s CE in the form of the militant Muslim Fulani and, ultimately, the northern part of the Oyo Empire, Ilorin, was conquered to become the Fulani Emirate of Ilorin, an outpost of the great Sokoto Caliphate (1804-1903 CE). The result of this loss was a domino effect that saw the Oyo Empire breaking up into smaller states which led to further competition and warfare between them. The consequence of this political decline for the Yoruba peoples was catastrophic as they had largely avoided being made slaves up to that point but were now by far the majority of those captured and shipped to the Americas until the slave trade ended here in the 1850s CE. The area of what is today the state of Nigeria became a British colony in 1861 CE, and in 1900 CE the protectorates of North and South Nigeria were formed. The two protectorates joined in 1914 CE, became a federation in 1954 CE, and finally gained independence in 1960 CE.