The Parson's Cause was a legal and political controversy that arose in the British colony of Virginia in the early 1760s. In response to the royal veto of the Two Penny Act, a policy passed by Virginia's House of Burgesses, a young lawyer named Patrick Henry successfully argued that the king had no right to interfere with colonial tax policies.

The controversy had its roots in tobacco, the staple crop and most lucrative export of Virginia. Hard currency was scarce throughout the Thirteen Colonies, leading many Virginians to pay their debts with tobacco notes, a paper currency that represented tobacco that had been inspected, packaged, and stored in local warehouses. The salaries of most of the colony's public officials, including Anglican priests, were also paid in tobacco. This led to a problem when, in the late 1750s, a string of severe droughts devastated the tobacco harvest, causing its price to leap from two pence to six pence per pound. This sudden inflation alarmed the debtors, mainly tobacco planters, whose contracts now obliged them to pay significantly more than had initially been agreed. They appealed to the House of Burgesses for protection, leading to the passage of the Two Penny Act, which allowed all debts payable in tobacco to be paid in hard currency instead, at the fixed rate of two pennies per pound, for one year.

The Two Penny Act was protested by a small, but vocal, group of Anglican clergymen, who claimed that it denied them the full value of their promised salaries. The clergy complained to the king's Privy Council in London, which agreed to repeal the act. Reverend James Maury used the Privy Council's veto as a pretext to sue his county for back pay, claiming the full amount of his salary that was denied to him by the act. His suit was successful, and it was determined that another jury would meet in the Hanover County Courthouse on 1 December 1763 to decide the amount of damages that Maury was to be paid. The defendants were represented by 27-year-old Patrick Henry, who argued that the king had violated his duty by vetoing the Two Penny Act; the act had been legally passed by the government of Virginia, and Henry claimed that any royal attempt to negate the people's will was nothing less than tyranny. Henry's passionate speech won over the jury, which awarded Maury the smallest sum possible, a single penny. The case made Henry's reputation, and his reasoning added greatly to the colonial discourse regarding 'taxation without representation' in the years leading up to the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

Tobacco as a Currency

By the time of the Parson's Cause case, tobacco was the lifeblood of Virginia. The history of European cultivation of the crop dated back to the time of Christopher Columbus, who had been introduced to tobacco by the natives of the West Indies shortly after his arrival. For the next century, the Spanish held a virtual monopoly on the trade of tobacco, which proved highly lucrative and was much sought after in European markets. In 1585, the English attempted to break into this market by cultivating their own tobacco in the Roanoke Colony, a settlement in modern-day North Carolina. But the Roanoke tobacco was considered a poor, worse-tasting alternative to its Spanish counterpart. It seemed that English dreams of cornering the tobacco market had dissipated, in much the same manner as the Roanoke Colony itself, which had mysteriously vanished by 1590.

Then, around 1610, an Englishman named John Rolfe arrived in Jamestown, a settlement that had been founded three years prior by the Virginia Company of London. The company's shareholders had intended the Jamestown Colony of Virginia to act as a permanent trade center in North America, but by 1610, the colony was struggling to survive, much less turn a profit. Jamestown's fortunes were reversed by Rolfe, who arrived with tobacco seeds that he had likely obtained from Trinidad. Rolfe successfully cultivated the first tobacco crop in Virginia in 1611, proving that the plant could not only survive but thrive in the colony's rich soil. Tobacco quickly became Virginia's staple crop, lining the pockets of planters and the colony's shareholders. In 1619, 20,000 pounds of tobacco were shipped from Virginia to England; that same year, enslaved Africans were sent to Virginia for the first time to cultivate the crop, a process that was heavily labor-intensive. In the following decades, most of Virginia's cultivated land was put toward tobacco production, land that was toiled on by thousands of enslaved Africans; the growth of the tobacco industry had led to the growth of slavery, an institution that soon spread to the other English colonies.

Tobacco quickly became an acceptable form of payment in Virginia, since the colony was initially prevented from minting its own coinage, and other forms of currency, such as English and Spanish coins, were rare in the North American colonies. As early as 1620, Virginians were conducting business negotiations with tobacco instead of hard currency; eventually, the colony began using a form of paper currency called 'tobacco notes', the value of which was backed up by tobacco that had been inspected, weighed, packaged, and stored in warehouses. It was typical for all public transactions to be paid using tobacco notes or even the plant itself, and even the salaries of officials were expressed in tobacco. In 1696, a statute mandated that the salaries of Virginia's Anglican priests were to be set at 16,000 pounds of tobacco per year; this statute was reaffirmed in 1748, with the approval of the king himself (Anglican priests were specified because the Anglican Church was the official church of Virginia at the time).

The Two Penny Act

Virginia's tobacco currency worked relatively well until 1755, when a severe drought killed off much of the colony's crops. Naturally, this newfound tobacco scarcity caused the price of the crop to leap from its usual rate of roughly 2 pence per pound to 6 pence per pound. Since most contracts and business dealings were expressed using tobacco, this created a problem; debtors had agreed to their contracts when tobacco was at a much lower price, and many of them would likely be financially ruined if they were forced to pay the new rate. The debtors, several of whom were influential tobacco planters, turned to the colony's legislature, the House of Burgesses, for protection. The Burgesses responded by issuing the so-called Two Penny Act, which allowed all debts payable in tobacco to be paid in cash instead, at a fixed rate of two pennies per pound, for a ten-month period.

Initially, the Two Penny Act did not cause much controversy; indeed, most creditors understood that their financial agreements had been made when the price of tobacco was lower and had not been expected to fluctuate so wildly, and therefore did not complain. However, a small group of Anglican clergymen protested the act arguing that, since 1696, they had been paid a salary equivalent to 16,000 pounds of tobacco. This had been reaffirmed in 1748, with the king's blessing no less, and the priests did not see any reason why they should not be paid in full just because the price of tobacco had changed. The protest was spearheaded by Reverend John Camm, a divinity professor at the College of William and Mary, who petitioned London to condemn the Two Penny Act as an attack "upon our establishment" (Encyclopedia Virginia). Camm's petition was signed by ten parish priests including Reverend Patrick Henry, uncle and namesake of the Founding Father.

The clergy's petition had no effect, since by the time it reached London, the ten-month period of the Two Penny Act had already expired, and the situation had returned to the status quo. The issue likely would have been forgotten had Virginia not experienced an even worse drought in 1758 that drastically reduced the tobacco crop and once again dramatically raised the prices. In October 1758, the House of Burgesses once again voted to reinstate the Two Penny Act, this time for the duration of a full year, in order to "enable the inhabitants of this colony to discharge their public dues, officer's fees, and other tobacco debts in money" (ibid). The act was approved by the governor's council and by the governor himself. Once again, most creditors, including most priests, understood and accepted the act, but a small group of Anglican clergy were livid; Reverend Jacob Rowe had an outburst in his Williamsburg home in which he denounced the Burgesses as scoundrels and promised to refuse to administer sacrament to any of them should they ask him for it.

Rowe was eventually forced to apologize before the House of Burgesses, but his angry sentiments were shared by several of his colleagues, who had already begun to fear the decline of Anglican influence in Virginia, as many non-Anglican Protestants were settling in the colony. In the autumn of 1758, 35 of the dissenting clergymen decided to send Reverend Camm to London, to go before the king's Privy Council and ask for the Two Penny Act to be repealed. In August 1759, Camm argued his case before the Privy Council which ruled in his favor. The Council reprimanded Virginia's governor and the House of Burgesses for enacting the statute before officially vetoing the Two Penny Act.

The Lawsuit

When word of the royal verdict arrived in Virginia, the governor and the colonial legislature were dismayed, seeing no reason why a bill that was rooted in legal precedent and passed using the correct procedures should be rejected. Still, there was nothing they could do. However, several Anglican priests were not content with simply basking in their victory and sued for the back pay that they believed was owed to them. Since the Privy Council had not decreed that the clergy had to be compensated, the first two lawsuits went against the priests. But the third, brought by Reverend James Maury of Fredericksville Parish, was a success; in 1762, a Hanover County court found in the reverend's favor and ordered a jury to meet at a later date to decide on the amount of damages Maury was to be awarded.

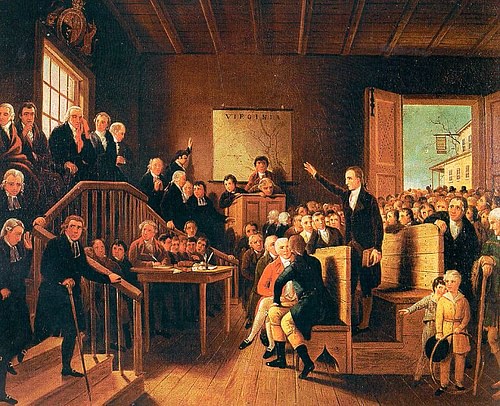

By this point, the eyes of the entire colony were on Maury's lawsuit, which was already being referred to as the 'Parson's Cause'. Reverend Camm had created quite a stir when he wrote an essay for the Virginia Gazette that denounced the House of Burgesses and defended Maury's case; Camm's essay was so unpopular that he had to travel to Maryland before he could find anyone willing to print a follow-up piece. The case in which Reverend Maury would be awarded his restitutions was scheduled for 1 December 1763 at the Hanover County Courthouse. Despite the cold and gloomy weather, the courthouse was packed with spectators to the point where, according to author Norine Dickson Campbell, "there were not enough benches for all. Some filed along the walls and into the doorway, and many stood outside the windows" (32).

Henry's Arguments

After the sheriff selected the members of the jury, the case began. Reverend Maury's counsel opened by interviewing two well-known tobacco dealers, asking what the market price of tobacco was in 1759. They eventually concluded that Maury was owed the sum of £144. The floor was then given over to the counsel for the defendants, a 27-year-old lawyer named Patrick Henry. Handsome, charming, and fond of revelry, Henry was a self-taught lawyer who had been admitted to the bar only three years earlier; few could have expected that he would do anything other than haggle with Maury's lawyers over a more reasonable price. Instead, Henry shocked the courtroom by condemning the clergy as "enemies of the community", who deserved not recompense but punishment. After all, the clergy's greed had prevented them from obeying a law that had been put in place by their fellow Virginians. Lambasting the ministers, whose number included his own uncle, Henry said:

We have heard a great deal about the benevolence and holy zeal of our reverend clergy, but how is this manifested? Do they manifest their zeal in the cause of religion and humanity by practicing the mild and benevolent precepts of the Gospel of Jesus? Do they feed the hungry and clothe the naked? Oh, no, gentlemen! Instead…these rapacious harpies would, were their powers equal to their will, snatch from the hearth of their honest parishioner his last hoecake, from the widow and her orphan children their last milk cow! The last bed, nay, the last blanket from the lying-in-woman! (Campbell, 35)

Henry had electrified the courtroom with these impassioned, scandalous words, but he was not yet finished. Next, he brought to his listeners' attention the colonial charter of Virginia, which gave the colony the right to make its own taxation laws. The Two Penny Act of 1758 was such a law, approved by the House of Burgesses, the governor's council, and the governor himself; the Privy Council's royal veto, therefore, had been unconstitutional. Henry argued that the king's duty was to protect the rights and liberties of his subjects, who in return offered their allegiance and support; by vetoing the Two Penny Act, the king had neglected this duty and was no longer worthy to rule. "A King," declared Henry, at the climax of his speech, "by disallowing acts of this salutary nature, far from being the father of his people, degenerates into a tyrant, and forfeits all rights to his subjects' obedience" (Middlekauff, 83).

At this, multiple voices were crying "treason!" and many demanded that Henry be reprimanded, but the presiding judge, Colonel John Henry, was Patrick's father and allowed the young lawyer to continue. Patrick Henry concluded by stating that the Two Penny Act should never have been repealed. But since it had been, and since the jury was legally required to award Reverend Maury something, Henry recommended that Maury be awarded the lowest possible sum. The jury, which had been moved to tears by Henry's oration, spent five minutes deliberating, after which it awarded Maury the sum of one penny.

Aftermath

Once the jury's decision was made, Henry was hoisted onto the shoulders of the ecstatic crowd who carried him from the courtroom. The incident turned him into a political celebrity almost overnight; in the months following the Parson's Cause, he gained 164 new clients and was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1764. He would use this newfound influence to become one of Virginia's leading voices during the upcoming American Revolution. Aside from boosting Henry's own career, the Parson's Cause is remembered today for contributing to the discourse surrounding Britain's right to tax the colonies. This would become a central issue in the coming years, with many American leaders like Samuel Adams echoing Henry's assertion that Britain had no constitutional right to interfere with colonial taxation laws; the right to self-taxation was protected in both the colonial charters and in the colonists' constitutional rights as Englishmen and was beyond the reach of the king and Parliament. The Parson's Cause, therefore, was a key ideological development in the leadup to the Revolution.