Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) was a French neo-impressionist painter whose vivid paintings with their flat, bold colours and use of mystical and ambiguous symbols revolutionised art. Never quite gaining success in his own lifetime, Gauguin was driven to Polynesia in search of a place unspoilt by modernity where he could express himself independent of all artistic conventions.

Early Life

Paul Gauguin was born in Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, Paris on 7 June 1848. His father, Clovis Gauguin, was a journalist and his mother, Aline Marie Chazal, was of Spanish noble blood. Clovis, a Republican, was obliged to leave France when Emperor Napoleon III took over the government in 1849. The family moved to Lima, Peru, but Clovis died of a heart attack mid-voyage. Paul spent the next six years of his childhood in Peru. In 1855, Aline and her children returned to France, living for a few years with relatives in Orléans before returning to Paris in 1861.

At the age of 17, Paul performed his military service in the Luzitano, a merchant navy ship which plied the route between Le Havre and Rio de Janeiro. In 1867 he switched to the Chili, which sailed to Polynesia. The next year he was serving in a naval warship and, in 1870, was involved in the Franco-Prussian War.

Out of the navy and back in France, Gauguin forged a successful career in finance in Paris. In November 1873, he married a Danish woman staying in Paris to widen her education, Mette-Sophie Gad (1850-1920), and the couple led a highly conventional life. Their first child, Émile, was born in September 1874 and their second, Aline, in December 1877. From 1873, Gauguin had been spending his weekends painting, but at some point, he realised that he was wasting his weekdays.

Impressionism

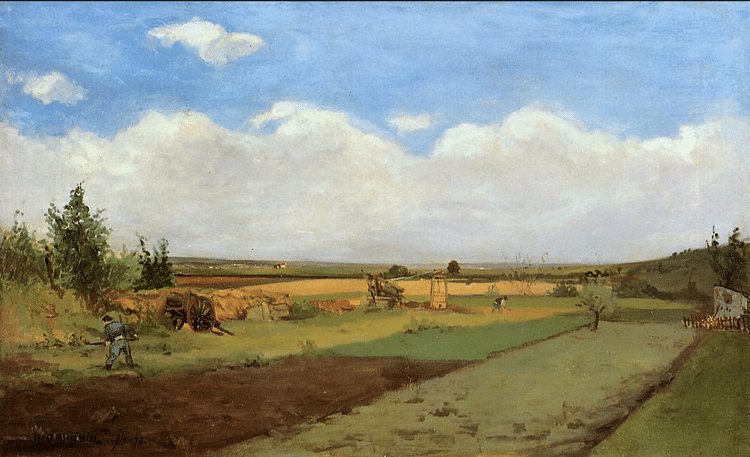

Gauguin's own interest in art and the new impressionist movement crossed paths in April 1874 in Paris at the First Impressionist Exhibition. Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) attempted to capture momentary effects of light and colour, and Gauguin was so impressed he was one of the few buyers at the exhibition. Gauguin began to entertain the idea of turning from hobbyist to professional painter. In 1876, he enrolled at the Académie Colarossi. The same year, Gauguin's Landscape at Viroflay was accepted by the Paris Salon, the institution which held a virtual monopoly on exhibiting fine art.

Gauguin was influenced above all by the impressionist and master of landscapes Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and the work of the realist painter Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Although one of the group of impressionists that frequently met in the cafés of Paris, the fiery Gauguin did not get along with everyone – Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) became a particular enemy, even if he greatly admired Cézanne's work. One good friend was another young maverick, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890).

The impressionists attempted to capture light, but it was not only this that affected Gauguin. They were using brighter colours and imaginative brushstrokes, painting outdoors instead of in the studio, and tackling new subjects like everyday street life. Gauguin was invited by his fellow artists to show his work in the Fourth Independent Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in April 1879. Later that year, he spent some time in Pontoise painting with Pisarro, a partnership they repeated in the summer of 1881. Gauguin showed paintings and one sculpture at the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition in 1880 and several new canvases at the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in 1881 and the seventh in 1882.

Following the 1882 Paris stock market crash, Gauguin finally decided to give up his work in the city and become a full-time artist from January 1883. In 1884, he moved to Rouen, hoping to find more sales for his paintings. This proved a mistake, and the entire family – by now composed of five children – moved to Copenhagen to be with Mette's family. Once there, Gauguin worked as a salesman for a French company producing nautical canvas, although not with any success. Family relations were also strained, but at least Gauguin secured an exhibition at the Society of Fine Art in Copenhagen, even if it failed to raise much public interest. Gauguin decided to leave Mette, who was now independent and working as a teacher and translator, and in June 1885, he returned to Paris and then Dieppe.

Money problems meant that Gauguin was obliged to work putting up posters in the street. The artist's poverty in this period is expressed in the following comment in a letter to Pissarro: "Paint – I don't even have the money to buy paints, so I confine myself to drawing" (Bouruet Aubertot, 250). He still participated in the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition in May 1886, contributing 19 works, but many of the old impressionists had moved on, and Gauguin was now an outsider. Nor was the artist given the comfortable position in society he had once enjoyed as a stockbroker and art collector. People pointed their fingers accusingly at his abandonment of his family. In June, he moved on to Pont-Aven in Brittany where the cost of living was much lower, one reason why it was popular with artists. Here Gauguin developed his distinctive style, adopting brighter colours and using thicker brushstrokes to create bold outlines and vivid areas of flat colour.

As winter came on, he moved back to Paris but was obliged to spend four weeks in hospital with angina. He next took up pottery making under the guidance of Ernest Chaplet (1835-1909). Still searching for a new avenue for his art, Gauguin decided to re-visit Panama in April 1887. As he explained in one letter to Mette in a correspondence that had remained unbroken by their physical separation, "I must get my energy back, and I'm going to Panama to live like a savage" (Hodge, 31). Unfortunately, finding any commissions for portraits amongst the wealthier inhabitants of Panama proved elusive, and the artist was obliged to work for a time as a labourer on the giant construction site that was on the way to becoming the Panama canal. He then contracted dysentery. Fed up with the whole idea, Gauguin left for the French colony of Martinique in June.

Paul Gauguin: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

Primitivism

St. Pierre on Martinique inspired Gauguin with its light and bright colours. Living in a primitive hut outside the town, the artist focussed on painting the islanders of African descent. Selling his avant-garde paintings, though, proved just as difficult as in Panama or Paris. Gauguin utilised a wide range of art styles which show the influence of ancient and Asiatic art. He was experimenting with colour and perspective, frequently using symbols to provoke emotion within his compositions, and presenting scenes which were deliberately simplified. This style became known as primitivism or, more specifically, synthetism or cloisonnism, and was inspired by medieval enamelwork (cloisonné), Japanese prints, and native art where strong dark outlines were used to surround areas of simple colour, much like images in a stained glass window. This style was one of several that replaced impressionism and so is labelled post-impressionism, even if that term was not coined until 1910.

Gauguin soon ran out of money, even being obliged to sell his watch, and he caught malaria. The artist was trapped since he could not pay for his fare back to France. The only way out was to find a ship that would employ him to work his passage across the Atlantic. This he managed, and Gauguin returned to Paris in 1887. Then things started to pick up. His paintings from Martinique caused enough of a stir for the art dealer Theo van Gogh (1857-1891) to buy a few; he also bought some of Gauguin's ceramics. These sales and others allowed the artist to relocate to Pont-Aven again in February 1888. Brittany was hardly a primitive location, but it did have an appeal to artists as an antidote to the oversophistication of Paris. As Gauguin himself wrote in a letter, "I love Brittany. There is something wild and primitive about it. When my wooden clogs strike this granite ground, I hear the dull, muffled, powerful tone I seek in my painting" (Howard, 208). His new style of this period combining symbolism, a flat perspective, and outlines around solid fields of bold colours can be best seen in Vision after the Sermon, which shows Breton women in their traditional headgear turned towards an angel wrestling with the biblical figure Jacob. It was in Brittany that Gauguin began a relationship with Madeleine Bernard (1871-1895), younger sister of the artist Émile Bernard (1868-1941).

With Van Gogh in Arles

By October 1888, Gauguin had racked up debts in Pont-Aven, but he was rescued by Theo van Gogh and his brother Vincent who invited Gauguin to join him in Arles in southern France. They shared the Yellow House in Arles, Vincent having made it a pleasant home decorated with his canvases, including several of sunflowers that Gauguin greatly admired. The two artists painted successfully for a while – producing 20 canvases each – but their strong characters and different views on art caused tremendous clashes. After one fiery discussion in late December, Gauguin left to spend the night in a hotel. The next morning, he returned to the Yellow House to discover Vincent had cut off one of his ears in the first of many mental breakdowns the artist suffered. Gauguin left for Paris immediately.

In February 1889, several of Gauguin's paintings were exhibited in an exhibition in Brussels organised by the noted dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922). In the same month, the artist moved back to Pont-Aven, but it had by now become too touristy and so he moved on to the fishing village of Le Pouldu where he headed a group of like-minded artists who regarded Gauguin as their leader. He also acquired a mistress, Juliette Huet (aka Huais, 1866-1955), with whom he had a daughter.

Tahiti & the South Seas

In April 1891, Gauguin decided to leave France and head for Tahiti; he left both Juliette and his wife Mette and five children behind but did visit the latter in Copenhagen in March before he sailed to the Pacific. The voyage was paid for by auctioning 30 of his paintings. An agreement with the French Ministry of Fine Arts that Gauguin capture on canvas the local customs of Tahiti allowed him to get a discount on the voyage.

Settling in Papeete, Gauguin was charmed by his natural surroundings but disappointed at the degree to which colonization had eroded the indigenous culture. Once again, he struggled to earn a living as an artist and managed to find only one commission for a portrait. Looking for a less Europeanised place, Gauguin moved to the remote village of Mataiea in November 1891, where he rented a bamboo hut. Even here, Gauguin needed money to live, but he struggled to earn any cash and received very little from France despite sending canvases back there for sale. A planned exhibition in Copenhagen failed to bring any significant sales either.

The artist kept notes on local customs and an illustrated diary of his experiences with the Tahitian title Noa Noa ('fragrance'). He also began to share his hut with a 13-year old Tahitian called Tehamana (aka Tehura). Thirteen was then the age of consent on the islands. Together they had a child. Gauguin wrote, "I started working again and happiness came on happiness. Every day, at the first glimmer of sunrise, the light inside my room was radiant. The gold of Tehura's face flooded everything around it" (Hodge, 67). Things picked up financially in 1892 when a passing schooner captain bought one painting and commissioned another. By June 1893, Gauguin was ready to return to France, and he landed in Marseilles in August.

Return to Paris

Gauguin rented a studio in Paris with money that Mette had saved up from sales while he was in Tahiti. Fortuitously, Gauguin then inherited a large sum of money from his uncle Isidore in Orléans. The artist refused to share very much of the windfall with Mette, and this caused the final rift between them, even if they had planned to reunite. Mette was furious that Gauguin would still not support his children. Gauguin seemed indifferent and now lived with another mistress and another young teen, a Javanese called Anna. Gauguin's lifestyle and deliberately eccentric clothes and manners continued to shock society and those with influence in the art establishment.

Meanwhile, Durand-Ruel organised an exhibition of Gauguin's Tahitian work in Paris in November 1893. The critics were less than enthusiastic, and the sales did not cover the exhibition's costs. Even artists gave a mixed reaction. Monet and Renoir thought Gauguin's works awful, but Degas greatly admired them. In 1894, Gauguin moved on to Brussels and then returned to Brittany. Gauguin's extravagant personality seemed to attract incidents and, in May, he was involved in a fight with a bunch of sailors that ended in a broken leg for the artist. After a long recovery process, Gauguin sold off his remaining paintings to fund another trip to the South Seas. In June 1895, Gauguin left France, he hoped it would be definitively, and in that he was right. En route to Papeete, he stopped off at Aukland and was much impressed by the Maori art he saw there.

Tahiti & the Marquesas

Back in Tahiti in September, the island seemed to have sunk further under the weight of European colonialization. Searching for the last vestiges of indigenous culture, he moved to the tiny village of Punaauia to nurse his failing health and paint. Living with him was a local girl called Pau'ura a Tai (aka Pahura). A small amount of money trickled to him from Paris, where a few dealers were at least occasionally selling his works but at disappointingly low prices. Gauguin could not understand why he had enjoyed such a great reputation with fellow artists but that this had not materialised into public recognition and sales. "What have I achieved? Utter defeat…Bad luck has dogged me relentlessly" Gauguin wrote (Hodge, 82). He continued to paint feverishly, blending local colour with all the art he had ever encountered and his own vivid imagination.

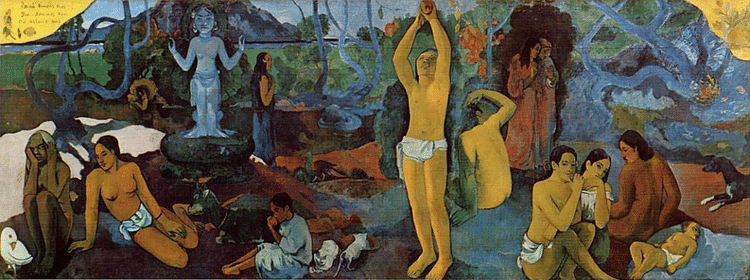

By 1897, Gauguin was convinced that his health problems could only worsen, and he attempted suicide. From rock bottom, the artist within him then rose to create what he considered the finest painting of his career: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? This huge frieze-like canvas measures 4.5 metres (15 ft) in length, but none of its ambiguous and mystical figures presents an easy answer to the questions in the painting's title. Despite his artistic triumph, ordinary life proved as difficult as ever. Indeed, he was obliged to turn full circle and return to what he most detested: an office job in Papeete. At least he could now pay off his debts and buy paints again. Then, sales in Paris and a contract with a dealer for more meant that Gauguin could return to being a full-time artist in 1899. Back in Europe, Gauguin's reputation was steadily building again, and his works were bought by noted collectors.

In September 1901, Gauguin moved on to Hiva Oa (called Dominique at the time) in the Marquesas Islands. He was looking for a more authentic insight into an unspoilt Polynesia, and it was much cheaper. He named his primitive hut Maison du Jouir ('House of Pleasure') and once again acquired a young companion, Marie Rose, the daughter of a tribal chief. Freshly inspired by his surroundings of volcanic hills and tropical foliage, the artist painted and sketched with abandon, continuing to reject academic art and its current preoccupation with light and perspective but also softening his palette compared to Tahiti. The artist's domestic arrangements and frequent parties outraged the local missionaries, especially when Marie Rose and Gauguin had a daughter, Tahiatikaomata. Gauguin's health continued to deteriorate, and this restricted his painting; instead, he wrote his memoirs: Avant et Après ('Before and After').

Death & Legacy

After years of heart problems and the debilitating effects of syphilis, alcoholism, and malaria, Paul Gauguin died on 8 May 1903. He was buried in the cemetery at Hiva Oa, and his possessions and artworks were sold to whoever wanted them.

Gauguin's eclecticism and misleading simplicity expressed in paintings, prints, sculpture, and ceramics had only ever been appreciated by a few fellow artists and collectors during his own lifetime. In addition, Gauguin's unconventional lifestyle had overshadowed his artistic achievements. However, in the years following his death, several exhibitions were organised, and these helped permanently establish Gauguin's reputation.

Gauguin's use of strong colours and representation of primitive forms was hugely influential, inspiring such noted artists as Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Gauguin's preoccupation with combining bold colours and forms was a crucial inspiration for the synthetist movement, which championed natural forms, aesthetics, and emotion in art. Gauguin was specifically named as the inspiration for another group of artists who became known as Les Nabis and who created art with the aim of inspiring a spiritual reaction in the viewer. In the last year of his life, Gauguin had, then, been correct when he stated, "I feel I am right about art. In any case I will have done my duty; and there will always remain the memory of an artist who has set painting free" (Hodge, 6).