Pelops was a Greek hero and king of Pisa in Greek mythology. As the son of Tantalus, he was a member of the cursed House of Atreus, and was cruelly sacrificed by his father in a twisted way to test the gods – an act that backfired and led to Tantalus' eternal punishment.

The myths most commonly associated with Pelops include the disastrous feast with the gods in which he was killed and placed in a stew by his father and his quest to win the hand of Princess Hippodamia. He is considered a great Greek hero and was admired by the Greeks, with the Achaeans claiming him as their ancestor.

Family

Pelops was the son of Tantalus and the nymph Dione (some sources list his mother as Clytia or Euryanassa) and the grandson of Zeus and Atlas. He was the father of several sons and daughters, including Atreus, Thyestes, Dias, Corinthus, Cleon, Aelius, Nicippe, Archippe, and Eurydice with his wife Hippodamia, and the father of Chrysippus with either the nymph Axioche or Danais.

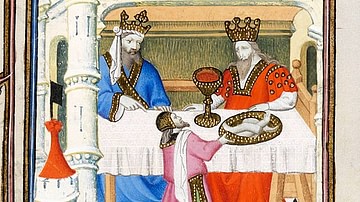

The Feast

The gods loved Tantalus dearly, and he was granted the honour of attending their feasts. Wanting to repay the Olympians for their hospitality, Tantalus invited the gods to feast at his table, either in Corinth or on Mount Sipylus (modern-day Mount Spil in Turkey). However, Tantalus soon discovered that he did not have enough food to feed his guests and devised a dark plan to test the gods' divine powers.

He killed his son Pelops, cut him up, and placed him in a stew. None of the gods were deceived except for Demeter, who was still mourning the loss of her daughter, Persephone, and was too distracted to notice what had been placed in front of her. Demeter reached for Pelops' shoulder and ate it without any hesitation. Angered and disgusted, Zeus ordered Hermes to collect Pelops' limbs and boil them in the same cauldron. Clotho, one of the Fates, removed him from the cauldron and brought him back to life. Demeter gave him an ivory shoulder to replace the one she had eaten.

Tantalus was punished harshly for his dark deeds. He was hanged from a tree in a lake and surrounded by fruit. Whenever he was thirsty, the water would recede and disappear. His hunger also went unsatisfied after a strong wind constantly pushed the fruit out of his reach.

After Pelops was brought back to life by the gods, he was blessed with beauty that did not go unnoticed by Poseidon, who carried him off to Mount Olympus in his chariot, which was pulled by golden horses. Pelops' descendants, the Pelopidae, had one shoulder that was as white as ivory as a sign of their ancestry.

Pelops & Hippodamia

Once he returned to earth, Pelops took over his father's rule of the Paphlagonians in Anatolia and also became king of Lydia and Phrygia. He was eventually run out of his kingdom by barbarian tribes and took refuge on Mount Sipylus. Ilus, the king of Troy, would not let him live in peace, so Pelops travelled across the Aegean Sea to start anew with his fortune and followers.

Hippodamia was the beautiful daughter of King Oenomaus of Pisa (Elis), who decided to offer her hand in marriage to any man who could beat him in a chariot race. Pelops decided to try his luck and travelled to Pisa. Oenomaus secretly desired his daughter and feared being overthrown, so he set up the challenge himself so that every suitor would fail in their mission. The suitor would have to take Hippodamia in his chariot and travel towards the Isthmus of Corinth. A fully-armed Oenomaus would ride in pursuit of his daughter. If the suitor and Hippodamia reached their destination safely, they could marry. However, if Oenomaus caught up with them, he would then kill the suitor. Oenomaus had the added advantage of possessing fast horses that were given to him by his father, Ares.

Hippodamia and Pelops fell in love, and Pelops knew he would need all the help he could get to win the race. He begged Poseidon for his assistance. Poseidon agreed to lend Pelops his winged chariot and horses. Pelops approached Oenomaus' charioteer, Myrtilus (a son of Hermes), and promised him half the kingdom and the chance to spend the night with Hippodamia if he would betray his master. Myrtilus, who was in love with Hippodamia himself, did not hesitate to help Pelops. He removed the lynchpins from Oenomaus' chariot wheels and replaced them with wax ones.

Pelops made a sacrifice to Athena before the race began. Oenomaus was hot on Pelops' trail and had his spear poised, ready to attack Pelops from the back. All of a sudden, the wheels of Oenomaus' chariot collapsed, and Oenomaus got tangled up in the reins and was dragged to his death. As Pelops, Hippodamia, and Myrtilus celebrated their victory, Pelops realised that he no longer wanted to keep his promise to Myrtilus and threw him into the sea. Other sources state that Hippodamia accused Myrtilus of trying to rape her, and Pelops killed him in a fit of anger. Myrtilus cursed Pelops and his family as he fell to his death into the sea, which was thereafter named after him (Myrtoan Sea).

King Pelops

After Myrtilus' death, Pelops was purified by Hephaestus. He returned to Pisa and married Hippodamia, becoming king. He took over the surrounding areas, including Olympia, and named the region 'Peloponnese' (Island of Pelops). After failing to defeat King Stymphalus of Arcadia, he resorted to killing him and spread his body pieces far and wide.

After capturing Olympia, Pelops restored the Olympic Games to its full glory. As king, he built the first temple dedicated to Hermes in the Peloponnese to atone for the murder of Myrtilus. He also paid him heroic honours in an attempt to appease his spirit. Pelops also ensured that the dead suitors of Hippodamia were honoured by building a large barrow over their graves in memory of them.

Pelops' Sons

Pelops had many sons with Hippodamia; however, his favourite son was Chrysippus, the son he shared with Axioche or Danais. This did not go unnoticed by Pelops' oldest sons, Atreus and Thyestes, who envied Chrysippus and devised a plan with their mother, Hippodamia, to get rid of him. They murdered him and threw his body down a well. According to other traditions, Atreus and Thyestes refused to kill Chrysippus, and their mother acted alone. A grieving Pelops expelled his sons from Pisa, and Hippodamia fled to Argolis, fearing her husband's wrath, and killed herself. After she had died, Pelops took her body to Olympia.

After being banished, Atreus and Thyestes were in conflict with one another, fighting for the throne of Mycenae. The bloodshed and death that followed them both further proved that the House of Atreus was indeed cursed.

Pelops' Bone

According to the ancient geographer and writer Pausanias (c. 115 to c. 180 CE) in his Description of Greece, during the Trojan War, there was a prophecy that the Greek army would fail to capture Troy unless they collected Hercules' bow and a bone from Pelops. The Greek hero Philoktetes was tasked with travelling to Pisa to retrieve the bone. He was successful in his quest; however, on the journey back to Troy, their ship was hit by a storm and sunk, carrying Pelops' bone to the bottom of the sea.

Many years after the fall of Troy, a fisherman named Damarmenos caught Pelops' bone in his net. He kept it hidden in the sand, but his curiosity got the better of him, and he travelled to Delphi to ask whose bone it was. An ambassador from Elis also happened to be at Delphi at the same time, seeking a cure for the plague. The Pythian priestess informed him that the Eleans must rescue Pelops' bones and ordered Damarmenos to hand over his find. The people of Elis were so grateful to Damarmenos that they made him and his descendants the guardian of Pelops' bone.

Legacy

Throughout his lifetime and after his death, Pelops was admired greatly throughout Greece, with some considering him to be one of the greatest Greek heroes of all time. It was even said that Pelops was honoured above all other Greek heroes after he had died.

Pausanias states that after Pelops' death, his bones were placed in a bronze chest and preserved in a sanctuary that was dedicated to him by his grandson, Tirynthian Hercules. Every year, young men travelled to the Sanctuary of Pelops, where they would make offerings of their blood at the altar. The magistrates offered Pelops an annual sacrifice consisting of a black ram that had been cooked on a fire of white poplar wood.

Pelops' chariot was presented on the roof of the Anactorium in Phliasia (Peloponnese), while the Sicyonians (from Sicyon) had his gold-hilted sword in their possession and presented it in their treasury at Olympia. His royal sceptre was kept at Chaeronea and was believed to have been the last surviving work of Hephaestus. It was a personal gift from Zeus. Pelops and Oenomaus' famous chariot race was immortalised on a gilded shield that adorned the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and on a cedar-wood chest that hid the dictator of Corinth, Kypselos, when he was a baby.