The Ten Thousand Immortals were the elite force of the Persian army of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). They formed the king's personal bodyguard and were also considered the shock troops of the infantry in Persian warfare. They are among the most famous fighting forces of the ancient world.

Their name comes from the policy of always keeping their number at exactly 10,000; if one of their number were killed or could not otherwise fulfill his responsibilities, another was chosen to replace him, thus giving the impression that they could not be killed and so were immortal and invincible.

They are first mentioned by Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) in his Histories (VII.83.1, VII.211.1, VIII.113.2), and later writers who mention them such as Heracleides of Cumae (c. 350 BCE) or Athenaeus of Naucratis (l. 2nd/early 3rd century CE) and others are thought to have drawn on Herodotus' work. Whether writers such as Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE) or Polyaenus (l. 2nd century CE) who also mention them drew on Herodotus as well seems unlikely since they both provide information not found in Herodotus' Histories. Xenophon, who fought as a mercenary in Persia for Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BCE) would have no doubt heard stories of the Immortals.

Herodotus has been criticized – by ancient as well as modern writers – for errors in his work as well as embellishments and exaggerations and so some modern scholars have advanced the claim that there never were any 10,000 Immortals in the Persian army (ignoring or explaining away their mention by Xenophon and Polyaenus) arguing that Herodotus confused the Old Persian word for “follower” (anusiya) with the word anausa (“immortal”). According to this claim, then, the 10,000 Immortals were no more than a unit of infantry and Herodotus inflated their reputation through his penchant for story-telling.

This claim is challenged, however, by the accounts of the Immortals as the elite unit in the later Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). The founder of that empire, Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE), organized his military to mirror that of the Achaemenid Empire (drawing equally from models such as Parthian warfare and the Roman army) and included the 10,000 Immortals. The only difference between the Sassanian and Achaemenid Immortals, besides the latter's better armor and equipment, was that the Sassanian were cavalry (known as the javidan or zhayedan) while the Achaemenid were infantry. In both empires, the Immortals were chosen from the warriors who had proven themselves worthy both in martial skill and quality of character and were the most formidable unit in the armies of two of the greatest empires of the ancient world.

Origin & Training

The Immortals were first formed under the reign of Cyrus II (The Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE), founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus the Great defeated the Medes, who had controlled the region, and then embarked on a series of campaigns to expand his territory, conquering Lydia in 546 BCE, Elam in 540 BCE, and Babylon in 539 BCE. He then included Median and Elamite warriors in his army, often giving Medes and Elamites command positions.

According to Iranian historical tradition, the Immortals were first organized by the commander Pantea Arteshbod with her husband General Aryasb, possibly after their participation in the Battle of Opis in 539 BCE. Pantea Arteshbod is said to have governed Babylon after its fall to Cyrus and have first instituted the elite guard of the Immortals at that time. She is also said to have been their first commander which is quite likely since evidence of women serving in high-ranking positions in the Persian military has long been substantiated by physical evidence in tombs and the accounts of Greek and Roman historians.

Xenophon, in his Cyropaedia (a semi-fictional account of Cyrus' life and reign), claims that Cyrus formed his palace guard from the best warriors of the army and then created an elite unit from the best of the best:

Accordingly, he took from among them ten thousand spearmen, who kept guard about the palace day and night, whenever he was in residence; but whenever he went away anywhere, they went along drawn up in order on either side of him. (VII.5.68)

These were Persians and Medes and are thought to have taken part in Cyrus' various campaigns against Lydia, Elam, and Babylon as the king's personal guard but also as shock troops. They are also thought to have gone with Cyrus' son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) on his Egyptian campaign in 525 BCE.

Cyrus created a standing army (the spada) but kept the old levy system known as the kara. Scholar Stefan G. Chrissanthos comments:

Initially, the Persian army consisted of a militia of the king's Persian subjects. However, not all Persians participated. Only those with sufficient wealth to procure their own military equipment were liable for service; therefore, the levy, or kara, represented the wealthier elements of Persian society. (21)

The kara would remain an integral aspect of the Persian army, but a satrap (Persian governor) of a satrapy (province) was expected to provide conscripts for military service and also either lead them in battle or appoint a trusted general for that purpose. The conscripts came from all the subject nations of the empire, from Anatolia to Egypt to Central Asia, but the core of the spada were Persians and Medes, and it was from this group that the Immortals were chosen. Chrissanthos describes the training required of the sons of Persian and Median nobles:

From the age of five, chosen nobles were trained to use the bow, throw the javelin, and ride. They were trained to endure cold, heat, and rain and to march under any type of difficult weather. Their food was spare and they were taught to live off the land if necessary. They hunted on a regular basis and competed in athletic contests, including running and tests of endurance. Their character was not ignored; they were taught Persian religion and respect for their god, Ahura Mazda, and they learned the history of their people and especially the noble deeds of heroic men. They were instructed on their duties to the Persian god, the Persian people, and especially the Persian king and the Achaemenid family. Last, they were trained to speak the truth, an item that was approvingly noted by numerous Greek historians. (23)

Military service began at the age of 20, and professional soldiers were allowed to retire at 50; afterwards they were rewarded with land grants and a pension in thanks for their service.

Uniform & Weapons

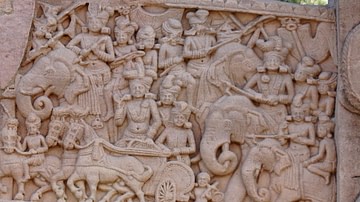

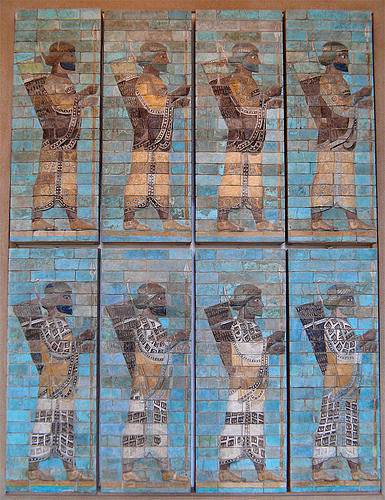

Herodotus provides a description of the Persian forces of the Achaemenid army in Book VII.61. It has often been claimed that the images of Persian warriors at the cities of Susa and Persepolis represent the 10,000 Immortals but, based on this description, it is more likely that they are representations of the regular Persian army with, perhaps, the occasional image of an Immortal:

On their heads they wore tiaras, as they call them, which are loose, felt caps, and their bodies were clothed in colorful tunics with sleeves (and breastplates) of iron plate, looking rather like fish-scales. Their legs were covered in trousers and instead of normal shields they carried pieces of wickerwork. They had quivers hanging under their shields, short spears, large bows, arrows made of cane, and also daggers hanging from their belts down beside their right thighs. (VII.61)

Herodotus also describes the personal apparel of the Immortals and the baggage train which followed them into battle:

Their equipment has already been described, but they were also conspicuous for the huge amount of gold they wore about their persons. They also brought covered wagons for their concubines, sizeable and well-equipped retinues of slaves, and their own personal provisions, separate from those of the other soldiers, transported by camels and yoke-animals. (VII.83)

Under the Sassanian Empire, the Immortals (as noted) were cavalry units. Their uniform and weapons are described by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (l. c. 330 - c. 400 CE) who provides the most complete description of the Persian knight:

All the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces [the helmets] were so skillfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath. Of these some who were armed with pikes, stood so motionless that you would have thought them held fast by clamps of bronze. (25.1, 12-13)

Their weapons were the sword, battle-axe, mace, javelin, and lance. They also carried two composite bows, two bowstrings, a quiver with 30 arrows and, sometimes a sling with stones or pellets. Some modern-day scholars differentiate between two types of mounted Sassanian warriors: clibanarii and cataphracts. Clibanarii had armored horses while the cataphracts did not. It should be noted, however, that this distinction is not recognized by all scholars and many regard the Immortals of the Sassanian Empire as cataphracts who rode horses as heavily armored as they were themselves.

Famous Engagements under Achaemenid Empire

The Immortals unit was continued under Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE), and it is assumed they took part in the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE when Darius I invaded Greece during the Persian Wars and was defeated. Easily the most famous engagement of the Immortals, however, was at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE under the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE). Xerxes I launched his massive invasion of Greece in retaliation for the Persian defeat at Marathon ten years earlier but was met by stiff resistance at the pass of Thermopylae by the Spartan general Leonidas I (r. 490-480 BCE) who, realizing his precarious position against numerically superior forces, sent away the majority of the defending troops and met the enemy primarily with the 300 Spartans under his direct command.

Xerxes I at first sent his Medes and Cissians against the Spartans, but they were driven back. Afterwards, he directed his Immortals against them, as Herodotus describes:

After a while, the Median troops were withdrawn, badly mauled, and their place was taken by the Immortals, as Xerxes called them – the Persian battalion commanded by Hydarnes. It was expected that they would easily finish the job, but when they came to engage the Greeks, they were no more successful than the Medes had been. The result was no different, because the factors were the same: they were fighting in a restricted area, using spears which were shorter than those wielded by the Greeks, and could not take advantage of their numerical superiority. (VII.211)

The central weakness of the Immortals against the Greeks – at Thermopylae and other engagements – was the inferiority of their weapons and body armor when compared to that of the Greeks. The Persians never had to concern themselves with these aspects of warfare prior to their engagements with Greece because the other regions they had encountered – the Lydians, Elamites, and others – used the same weapons and armor they did.

The more durable and resistant Greek shields and body armor, as well as their more effective weapons, outstripped those of the Persians and placed the Persian army at a distinct disadvantage, especially significant at the Battle of Platea in 479 BCE which was most likely fought by regular Persian forces, not the Immortals, who seem to have withdrawn with Xerxes I after the Persian defeat at Salamis in 480 BCE.

The Immortals continued as the elite corps throughout the remainder of the Achaemenid Empire up through the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE) against the forces of Alexander the Great, under Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) where they were defeated through a combination of Alexander's superior military tactics and their own weaponry. The corps was kept intact by Alexander (who styled himself as the successor to Darius III and is often referred to as the last king of the Achaemenid Empire). Polyaenus attests to Alexander's policy of keeping the Immortals intact in his Strategems:

When deciding legal cases among the Macedonians or the Greeks, Alexander preferred to have a modest and common courtroom. but among the barbarians he preferred a brilliant courtroom suitable for a general, astonishing the barbarians even by the courtroom's appearance. When deciding cases among the Bactrians, Hyrcanians, and Indians, he had a tent made as follows: the tent was large enough for 100 couches; fifty gold pillars supported it; embroidered gold canopies, stretched out above, covered the place. Inside the tent 500 Persian Apple Bearers stood first, dressed in purple and yellow clothing. After the Apple Bearers stood an equal number of archers in different clothing, for some wore flame-colored, some dark blue, and some scarlet. In front of these stood Macedonian Silver Shields, 500 of the tallest men. In the middle of the room stood the gold throne, on which Alexander sat to give audiences. Bodyguards stood on each side when the king heard cases. In a circle around the tent stood the corps of elephants Alexander had equipped, and 1,000 Macedonians wearing Macedonian apparel. Next to these were 500 Elamites dressed in purple, and after them, in a circle around them, 10,000 Persians, the handsomest and tallest of them, adorned with Persian decorations, and all carrying short swords. Such was Alexander's courtroom among the barbarians. (4.3.24)

The “Apple Bearers” Polyaenus mentions were the Persian officers who had a gold counterbalance at the bottom of their spears; regular troops had one of silver. They were known as “Apple Bearers” because the round counterbalance looked like an apple. The Immortals carried this same weaponry.

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, his empire was divided among four of his generals, and Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE) took the region of Central Asia and Mesopotamia, founding the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE). Seleucus I continued Alexander's policies and kept the basic form of the Achaemenid Empire but whether he also retained the corps of the Immortals is unknown.

Parthian Innovations & the Sassanid Empire

The Seleucids were succeeded by the Parthian Empire who decentralized the government and established a feudal system, essentially returning to the paradigm of the kara in which satraps decreed a levy of troops when the need arose. The Parthians were aware of the weakness of a centralized government with a standing army which had to be mobilized and set in motion and so allowed for different satrapies to raise their own forces to deal with threats and had no need for a central corps of Immortals. They divided their army into light and heavy cavalry with infantry playing a minor role in engagements.

The heavy cavalry of the Parthians would be taken as a model by Ardashir I when he founded the Sassanian Empire and would form the basic paradigm of the Sassanian Immortals. These warriors, as noted, were heavily armed cavalry and served as the backbone of the Sassanian military. The Sassanian army was so effective that it was able to repeatedly defeat the legions of the Roman Empire, defend Sassanian territory from other incursions, and maintain stability for almost 400 years.

Under the reign of Kosrau I (also known as Anushirvan the Just, r. 531-579 CE), the military, including the Immortals, was at its height but could not defend against the more mobile – and numerous – forces of the Muslim Arabs who defeated the Sassanians in 651 CE through their use of fleet-footed archers and camel-mounted cavalry who could maneuver more easily on rough or sandy terrain. After the Muslim Arab conquest and fall of the Sassanian Empire, the Persian army – including the Immortals – was disbanded.

Conclusion

The Immortals were revived in the 20th century CE under the reign of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941-1979 CE) who instituted a unit of all-volunteer soldiers known as the Javidan Guard (comprising 4,000-5,000 soldiers) as his “Immortals” in an effort to link himself to the illustrious past of the Achaemenid and Sassanian Persian empires. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979 CE, the Javidan Guard was disbanded.

In the present day, unfortunately, the Immortals are best known in popular culture through their depiction in Frank Miller's 1998 CE graphic novel 300 and the 2006 CE film of the same name which was based on it, relating the story of the Battle of Thermopylae and the heroic stand of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans in 480 BCE. In these works, the Immortals are reimagined as malformed beasts (as is Xerxes I) juxtaposed against the heroic Greek warriors under Leonidas.

These depictions serve no purpose other than to denigrate the image of some of the greatest warriors of the ancient world. The Immortals were far from subhuman, snarling animals; they were some of the most refined, cultured, and courageous warriors to take the field in ancient combat and deserve more respect than being remembered primarily as the savage adversaries of the Greeks at Thermopylae. The Persians, in fact, did not regard the defeats of 490 or 480 BCE as major defeats and, most likely, were confident that the Immortals would later lead the army to victory, as they would many times afterwards and, especially, under the Sassanian Empire.