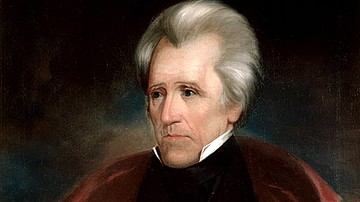

The Petticoat affair, also called the Eaton affair, was a political scandal that rocked Washington, D.C., from 1829 to 1831, during the early years of Andrew Jackson's presidency. Revolving around the rumored sexual promiscuity of Peggy Eaton, wife of the US secretary of war, the affair divided Jackson's cabinet and reshuffled the leadership of the fledgling Democratic Party.

Background

Shortly after winning the presidency in the election of 1828, General Andrew Jackson set about building his cabinet. Aside from Martin Van Buren – a prominent New York politician selected as secretary of state – the president's cabinet consisted of little-known figures who were chosen mostly for their loyalty to Jackson himself or because of their hatred for Henry Clay, Jackson's chief political rival. The most consequential of these appointments would prove to be John Henry Eaton as secretary of war. A former US senator from Tennessee, Eaton was a longtime Jackson loyalist who had become one of the general's few close friends. The pair had met in the Tennessee militia during the War of 1812, with Eaton having served under Jackson in the famous Battle of New Orleans (8 January 1815). In 1817, Eaton had completed the first biography of Jackson, in which he praised the general's career and defended some of his more controversial actions. Suffice to say, Eaton was someone Jackson felt he could trust – for Jackson, as a Washington outsider who wholeheartedly believed the national capital was full of corruption, this kind of trust was a rare commodity, indeed.

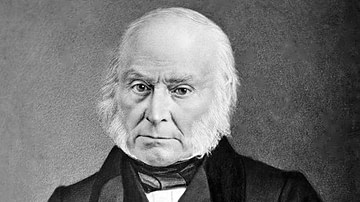

The new president's conclusion that Washington was corrupt had not sprung from nowhere. Despite having won the popular vote in the previous presidential election of 1824, Jackson had lost the race to John Quincy Adams, who had been able to obtain more electoral votes when the final decision was handed to the House of Representatives. A bitter Jackson attributed this to Adams' status as a Washington insider, a notion that seemed vindicated when Adams appointed Henry Clay as his secretary of state – Jackson and his followers believed that Adams and Clay had struck a 'corrupt bargain' whereby Clay was given the State Department in return for his support for Adams. Four years later, Jackson ran against Adams again in a presidential election that became vitriolic and personal. Adams' partisans had gone so far as to slander Jackson's marriage, claiming that his wife, Rachel Donelson Jackson, had not been legally divorced from her first spouse when the couple had first started living together as husband and wife. Deeply distraught by these accusations of bigamy, Rachel had died of a heart attack shortly after her husband's victory in December 1828, a loss Jackson blamed on his political opponents.

To make matters more difficult, Jackson also saw dissent from his own vice president, John C. Calhoun. While Jackson was a staunch Unionist who sought to expand the power of the presidency, Calhoun was a leading proponent of states' rights, who had recently begun to champion the right to nullification – that is, a state's ability to 'nullify' a federal law it believed to be unjust. With the economy of the South stifled by the unpopular Tariff of 1828 – known as the 'Tariff of Abominations' – and the looming question of slavery becoming more and more of a regional issue, states like Calhoun's native South Carolina were looking to fight back against the federal government through nullification, a step that many saw as a precursor to secession.

Finally, Jackson saw opposition in the form of the Second Bank of the United States, a rising institution that could perhaps rival the federal government as a center of power. With Jackson's vision of a strong presidency facing threats from all sides – 'corrupt' Washington insiders, proponents of states' rights and nullification, powerful bankers – it is easy to see why he valued loyalty in his cabinet. Little did he know, his cabinet members would soon have their loyalty tested in a scandal that would shape the development of the burgeoning Democratic Party. It would all begin with the secretary of war, John Henry Eaton – or, more specifically, with his wife.

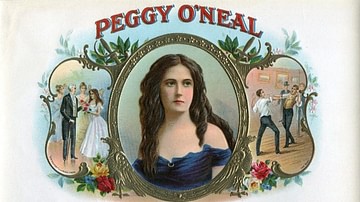

Peggy Eaton

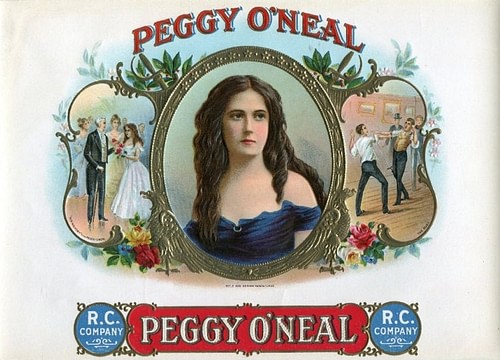

There was no denying that Margaret 'Peggy' O'Neill was a beautiful woman. One contemporary described her in a manner that would seem to invoke the image of Venus herself:

Her form, of medium height, straight and delicate, was of perfect proportions…her skin…of delicate white, tinged with red…her dark hair, very abundant, clustered in curls about her broad, expressive forehead. Her perfect nose, of almost Grecian proportions, and finely curved mouth, with a firm, round chin, completed a profile of faultless outlines.

(quoted in Meacham, 67)

The daughter of an innkeeper, Peggy had always been the subject of male attention. Looking back on her youth from old age, she would recall that she had had "the attentions of men, young and old," from the time she "was still in pantalets and rolling hoops" (ibid). In 1816, when she was only 17, Peggy O'Neill married John B. Timberlake, a 39-year-old purser (payroll officer) for the US Navy. Two years after their marriage, the Timberlakes struck up a friendship with John Eaton, who, at 28 years old, had just been elected to the US Senate. Eaton used his influence in the Senate to help pay Timberlake's debts and to get him assigned to the Navy's Mediterranean Squadron.

This act of patronage, according to the rumors that would later circulate, was actually an excuse to get Timberlake out of the picture while Eaton and Peggy struck up a passionate love affair. In April 1828, Timberlake died at sea – Eaton's detractors would later claim that he slit his own throat upon learning of his wife's affair, although medical examiners would conclude that he had really died of pneumonia. In any case, John Eaton married the widowed Peggy Timberlake on New Year's Day 1829, which raised several eyebrows since widows customarily observed longer periods of mourning before remarrying. Andrew Jackson, however, thought there was nothing wrong with the marriage; in fact, he had encouraged it, telling his friend that "if you love the woman, and she will have you, marry her by all means" (quoted in Meacham, 68).

Now, as the wife of a cabinet secretary, Peggy Eaton found herself moving in the highest circles of Washington society. But unfortunately, her unsavory reputation preceded her. Aside from the nasty rumors circulating about her late husband and hasty remarriage, she was known to have been something of a coquette. While Mrs. Eaton herself would not deny having had her share of lovers – "I do not claim to be a saint," she would write, "and lay no claim to be a model woman in any way" – the stories told about her were certainly slanderous and upset the sensibilities of the day. In one memorable tale, Mrs. Eaton was supposed to have walked by a man in a hallway without acknowledging him, having forgotten that they had once slept together. It did not help matters that Peggy Eaton could be brash and tactless in conversation, often speaking on matters that were considered unseemly for women to talk about, like politics.

The Wives of Washington Rebel

Cognizant of their own reputations, the other women of Washington sought to distance themselves from John Eaton's scandalous wife. At Jackson's inaugural ball, they refused to so much as speak to Peggy Eaton. A few days later, Mrs. Eaton paid a social call to Floride Calhoun, wife of the vice president. Although Mrs. Calhoun received her, she refused to return the courtesy by calling on the Eatons, which would have been proper. Instead, the Calhouns packed up and left Washington for South Carolina shortly thereafter, leaving many to whisper that Peggy Eaton had been deliberately snubbed by one of the foremost ladies in the nation. This emboldened several other prominent women to shun the Eatons as well. Those involved in this anti-Eaton clique included the wives of most of Jackson's other cabinet members as well as Emily Donelson, Jackson's own niece who carried out the duties of First Lady.

To a modern reader, the decision of the Washington wives to shun Peggy Eaton may come across as un-feminist. They were, after all, rejecting a woman based on her history of sexual proclivity. But as historian Daniel Walker Howe explains, these women believed themselves to be defending "the interests and honor of the female half of humanity". According to Howe:

They believed that no responsible woman should accord a man sexual favors without the assurance of support that went with marriage. A woman who broke ranks on this issue they considered a threat to all women. She encouraged men to make unwelcome advances. Therefore, she must be condemned severely even if it meant applying a double standard of morality, stricter for women than for men…the women who had the courage to…[stand] up to Andrew Jackson and [risk] their husbands' careers, insisted that expedient politics must not control moral principle.

(338)

When he learned of the wives' rejection of the Eatons, President Jackson became furious for several reasons. On a personal level, he was scarred by the slanderous attacks his enemies had made against his own marriage, which he still believed had caused the death of his beloved Rachel. This alone may have been enough to lead him to side with John Eaton, who, after all, had always been a good and loyal friend. But more importantly, the issue was causing dissent within Jackson's cabinet, something that a controlling figure like him could not tolerate. If he could not compel his own cabinet members to make peace with one another, how could he hope to stand up to Henry Clay, the banks, or errant states like South Carolina? Jackson repeatedly told his cabinet members to rein in their wives and force them to make peace with the Eatons. When this did not happen, he began to suspect that outside influences – Clay, perhaps, or even Vice President Calhoun – were purposefully encouraging the rift in his cabinet.

On 29 September 1829, Jackson held a cabinet meeting in which he hoped to resolve the issue once and for all. The president told his secretaries that the rumors surrounding Peggy Eaton were false and should be put to rest. When Jackson received pushback on this point, he lost his temper and shouted that Peggy Eaton was "as chaste as a virgin!" (Meacham, 115). Unsurprisingly, when the meeting broke up, no one's mind had been changed. In the coming months, the Eaton affair would become more of a headache and would eat up more of Jackson's time than any other issue. In one instance, Emily Donelson, pregnant and on the point of fainting, made a scene by refusing Peggy Eaton when she rushed over to help – Donelson's hatred for the Eatons would eventually cause Jackson to send her back to Tennessee, replacing her as White House hostess with his daughter-in-law Sarah Yorke Jackson. In another instance, John Eaton looked to satisfy his wife's honor by challenging two of his detractors, the secretary of the treasury and the pastor of the Washington Presbyterian church, to duels (both declined). Meanwhile, word of the affair began to spread, with former First Lady Louisa Adams remarking that the allegations against Peggy "are so public that my servants are telling them [at the] tea table" (ibid). If Jackson wanted to restore peace to his cabinet something would have to be done, and fast.

The Little Magician

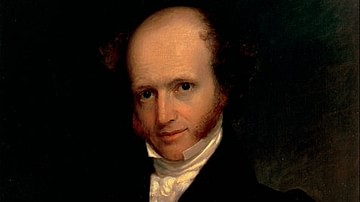

While most of Jackson's cabinet secretaries had been pushed into the anti-Eaton camp by their wives, Secretary of State Martin Van Buren – a widower – did not have this restraint. Van Buren was a crafty man who seemed to enjoy the game of politics for its own sake; nicknamed the "Fox of Kinderhook" or the "Little Magician", he had masterminded the political machine that had swept Jackson into the White House. Now, Van Buren was vying with Vice President Calhoun to secure the spot as Jackson's successor to the presidency. He saw the Eaton affair as a chance to increase his own standing in the president's eyes while simultaneously diminishing that of Calhoun, who, through the actions of his wife, was already associated with the anti-Eatons. And so, noting Jackson's support for the Eatons, Van Buren voiced his support for them as well. It was a consequential decision; James Parton, writing in the 1860s, would famously state that "the political history of the United States for the last thirty years dates from the moment when the soft hand of Mr. Van Buren touched Mrs. Eaton's knocker" (quoted in Howe, 339).

Throughout 1830, Van Buren ingratiated himself deeper within the president's trust by showing his support for Mr. and Mrs. Eaton. But at the same time, the 'Fox of Kinderhook' knew that the scandal would not come to an end so long as Eaton remained in the cabinet. So, in the spring of 1831, he devised a plan that he cautiously revealed to Jackson during one of their customary horseback rides outside the city. It was simple – each cabinet secretary would willingly resign to allow the president to build his cabinet up from scratch and end the roadblock to his administration. Although Jackson was initially wary, he gave his consent to the idea, as it was one of the only ways he could end the scandal while still saving face. Van Buren took the lead and was the first to resign, confident that his sacrifice would not go unrewarded. Eaton went next – despite Peggy's protestations that he stand his ground, John Eaton was persuaded by Van Buren to seek elected office in Tennessee and leave the headaches of the cabinet behind. The other secretaries were also strong-armed into resigning, with the sole exception of William Barry, the postmaster general; ostensibly, this was because the postmaster was not technically a part of the president's cabinet, but really, it was Barry's reward for keeping his wife in line.

The resignations were announced by the Washington Globe, the Jackson administration's mouthpiece newspaper, on 20 April 1831. The news spread across the nation like wildfire; for many of those outside of Washington, it was their first indication that there had been any scandal at all. Even at the time, it was clear that Van Buren had been behind the cabinet purge, with one newspaper writing: "Well indeed may Mr. Van Buren be called 'The Great Magician' for he raises his wand, and the whole Cabinet disappears" (quoted in Howe, 339). But, of course, the resignations were only the first part of Van Buren's plan; to raise himself up, he must next cast Calhoun down. He would find his opportunity when, in the reshuffling of cabinet and staff members, William Lewis became Jackson's favored private secretary. Lewis, as it happened, was also a confidante of Van Buren's and had no scruples showing the president letters that revealed that Calhoun had criticized Jackson's conduct during his invasion of Florida in 1817. For Jackson, who already blamed the Eaton affair on Calhoun and his wife Floride, this was proof enough that his vice president was against him. "I have this moment," Jackson declared, "[seen that which] proves Calhoun a villain" (quoted in Howe, 341).

Conclusion

Had the Petticoat affair been merely a White House sex scandal, it would have been an interesting historical anecdote, though not one of much importance. However, the affair had consequences that would shape the political history of the United States for the next few decades. Most importantly, it solidified Martin Van Buren's position within Jackson's favor while diminishing Calhoun's. Around this time, Jackson wrote:

I now know both Van Buren and Calhoun. The first I know to be a pure republican who had labored with an eye single to promote the best interests of his country, whilst the other, actuated alone by selfish ambition, has secretly employed all his talents in intrigue and deception to destroy them, and to disgrace my administration. The plot is unmasked.

(quoted in Howe, 341)

Because of this, Van Buren became Jackson's heir apparent. Indeed, Van Buren replaced Calhoun as vice president during Jackson's second term and would end up ascending to the presidency itself in 1837. Calhoun, meanwhile, would continue his fight for states' rights outside the administration and would square off against the federal government in the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33. But, while the shake-up of the power dynamics within Jackson's Democratic Party remains the most visible outcome of the Petticoat affair, Howe asserts that there were more subtle consequences:

[The affair] took place at a time when sexual behavior was undergoing reexamination by standards we now term 'Victorian', which laid increased emphasis on impulse control and strict personal accountability. Jackson did not directly challenge conventional sexual morality; he cast himself as a defender of female purity. Nevertheless, his stand on behalf of Margaret Eaton…tended to align the Democratic Party with those (mostly men) who resisted demands being made in the nineteenth century (mostly by women) for a stricter code of sexual morality…[this] may explain why Jackson's opposition, in the years to come, could count on more support from women's groups than the Democrats could.

(342)

The significance of the Petticoat affair, therefore, was to give Jackson greater control over his cabinet, reshuffle the leadership of the Democratic Party, and examine sexual morality and the place of women in society in an era that was becoming increasingly 'Victorian' in its moral standards. It remains a colorful chapter in the political history of the United States.