The Phoenician Religion, as in many other ancient cultures, was an inseparable part of everyday life. Gods such as Baal, Astarte, and Melqart had temples built in their name, offerings and sacrifices were regularly made to them, royalty performed as their high priests, and even ships carried their representations. Influenced by their predecessors and neighbours, the Phoenicians would spread their beliefs around the Mediterranean wherever they traded and established colonies, and their religion would continue to evolve and be perpetuated by their greatest colony of all, Carthage.

Sources

The details of the mythology, gods, and practices of the religion of the Phoenicians are few and far between because of the scarcity of surviving written records. These are principally from inscriptions excavated at various Phoenician cities as no single religious work such as a Phoenician equivalent of the Bible has survived, if there were ever one in the first place. Secondary sources, written long after the original Phoenician cities had declined, include snippets from Plutarch and Lucian, and surviving fragments of the work of the 1st-century CE historian Philo of Byblos, who himself quoted extensively from an earlier work by the Phoenician priest Sanchuniathon from Berytus. Once thought to be a mythical figure, archaeological excavations at Ugarit suggest that Sanchuniathon did actually exist.

Later historians such as the 5th-century Neo-Platonist Damascius quote the work of Mochus who wrote a history of Phoenicia but the original is now lost. There are also descriptions of the religious practices in the colonies of Phoenicia such as Carthage but these may well have absorbed local traditions and evolved over time so that a direct comparison with the original cities of Phoenicia may be problematic. Finally, there are passages within the Old Testament in which the Phoenicians are referred to as the Canaanites, where they are portrayed in a particularly negative light, as they are in Roman sources eager to portray the defeated Carthaginians and their Phoenician founders as wholly uncivilized and debauched.

Main Phoenician Gods

Although the historical sources present some difficulties of interpretation, the Phoenician Religion was remarkably constant, almost certainly due to the geography of the region where the Phoenicians were contained on the narrow coast of the Levant and backed by the mountains creating a border with their Aramaean and Hebrew neighbours. This is not to say it was uniform throughout the region as ancient Phoenicia was very much a collection of individual city-states rather than a single homogenous state. Each city had its chief god and pantheon for example, although some, such as Astarte, were worshipped throughout Phoenicia. The mythology of the origin of the world from the union of the primeval elements of Wind and Desire, followed by creatures hatched from an egg, which in turn generate humanity, also seems a common element in various cities' creation mythology. Beyond the big three cities of Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre, however, little is known of the religious practices at other Phoenician cities.

Byblos

El, Baalat, and Adonis were particularly worshipped at Byblos. El was of Semitic origin and, although equated with Eliun in the Bible, was a separate deity. He was important but not especially active in the daily life of the Phoenicians which led the Greeks to equate him with their Cronus. Baalat was a female deity associated with the earth and fertility. She is often referred to as Baalat Gebal or 'Lady Baalat of Byblos' and frequently mentioned in inscriptions where she is appealed to by kings so that their reign may be a successful one. Altars and monuments constructed from precious metals were dedicated to her. Her equivalents in other Near Eastern cultures were Ishtar, Innin, and Isis. Adonis is familiar from Greek mythology, and he represented for the Phoenicians the annual cycle of nature. Again he shares some characteristics with deities from neighbouring cultures, notably Osiris in Egypt and Tammuz of Babylon and Assyria.

Sidon

The most important god at Sidon was Baal, probably equivalent in function to El of Byblos, he was head of the pantheon but detached from everyday worship. The city did, though, have at least one temple dedicated to him. Much more prominent was Astarte (in Semitic inscriptions Ashtart and in the Bible Ashtoret) who had many temples dedicated to her and was the equivalent of Baalat at Byblos. The kings of Sidon were referred to as the priests of Astarte, and she frequently appears in surviving Phoenician inscriptions. In art she is often depicted with a crescent on her head, a reference to her close association with the moon. A third important god at Sidon was Eshmun, who does not appear before the 7th century BCE and was the equivalent of Adonis. Temples were built in his name and he was associated with healing, hence the Greeks identified him as their Asclepius.

Tyre

The highest god at Tyre was Melqart (also spelt Melkarth), equivalent to Baal at Sidon and probably confused with him in several passages of the Bible. Melqart, in addition, assumed some of the characteristics of both Adonis and Eshmun as he was the focus of a festival of resurrection each year (February-March). He was considered to represent the monarchy, the sea, hunting, and colonization. Further, he was responsible for the cities commercial success as the discoverer of the dye the Phoenicians extracted from the murex shellfish, which they used to create their famous purple cloth.

A long-lasting temple was dedicated to Melqart in the city and was famously visited by Herodotus, who described its entrance columns of gold and emeralds, and Alexander the Great, who made a sacrifice at its altar. The god was depicted on coins from Tyre in his guise as a sea god riding a hippocampus. Melqart was exported to many Phoenician colonies around the Mediterranean and was especially worshipped at Carthage, which sent annual tribute to the temple of Melqart at Tyre for the next few centuries. The Greeks identified him with Hercules. The other important deity at Tyre was Astarte, who also had her own temple, built by King Hiram in the 10th century BCE.

Other Gods

Besides those gods already mentioned the Phoenicians also worshipped Reshef, the god of fire and lightning; Dagon, the god of wheat, who was credited with inventing the plough; and Shadrapa, who was associated with snakes and healing. The god Chusor was thought to have invented iron and metalwork, and several deities were personifications of ideals, such as Sydyk and Misor, who represented Justice and Righteousness, respectively. Other gods were worshipped besides these, although fewer than in most ancient polytheistic religions. For these lesser gods it has become almost impossible to separate them from similar deities from neighbouring cultures, and the misunderstood associations applied by writers living centuries after the Phoenician culture had already been absorbed into the larger Mediterranean world.

Worship

The Phoenicians worshipped their gods, as we have seen, at purpose-built temples constructed on prominent locations in cities. Although the Phoenicians seem not to have built idols of their gods to place inside their temples as in many other ancient cultures. They also worshipped at natural sites which were considered sacred such as certain mountains, rivers, groves of trees, and even rocks. Rivers carried the names of the gods such as the Adonis River near Byblos and the Asclepius River which ran through Sidon. Here, at these natural sites, small shrines were built but sometimes larger structures too, for example at Aphka, a hill outside Byblos, where an entire sanctuary developed.

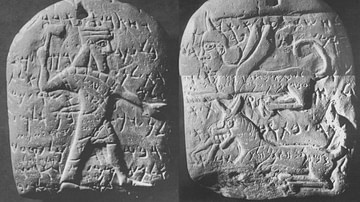

Ceremonies at such locations involved prayers, burning incense, the pouring of libations, and making offerings to the gods of animal sacrifices, foodstuffs, and precious goods. In addition, votive columns made from wood (aserah) or stone (betyl) were placed upon sacrificial altars. These were inscribed with prayers and decorated in festivals with flowers and tree boughs. In the case of Astarte, there was a tradition of women prostituting themselves in her honour. At particular times of danger, for example war or natural disaster, human sacrifices, largely children, were also made as indicated in exaggerated biblical and Roman references, in Phoenician colonies, and in art. Where this rite, in imitation of the sacrifice by El of his own son, was performed is known as a topheth (tophet), and the act of sacrifice molk. The victims were killed by fire, although it is not clear precisely how, and there is no archaeological evidence from Phoenicia itself, only its colonies.

The temples and sacred sites were administered by a class of priests and priestesses. It seems likely that the highest class of priests was closely associated with the royal family. Kings and princes may also have themselves performed religious functions. Not only did priests perform in public ceremonies and feasts but they also carried out funeral processes such as embalming. This fact and the presence of votive offerings in rock-cut tombs reveal that the Phoenicians did believe in an after-life. Inscriptions in tombs call for the dead not to be disturbed and that there was an underworld for those who had not led a pious life.