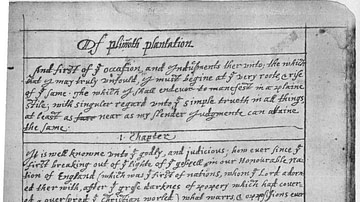

The Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty is the document drafted and signed on 22 March 1621 CE between governor John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) of the Plymouth Colony and the sachem (chief) Ousamequin (better known by his title Massasoit, l. c. 1581-1661 CE) of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The treaty established peaceful relations between the two parties and would be honored by both sides from the day of its signage until after the death of Massasoit in 1661 CE. The primary documents relating the event of the treaty come from the Plymouth Colony's two chroniclers William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE) in their works Of Plymouth Plantation (by Bradford, published 1856 CE) and Mourt's Relation (by Bradford and Winslow, published 1622 CE), both first-hand accounts of the Plymouth Colony's history.

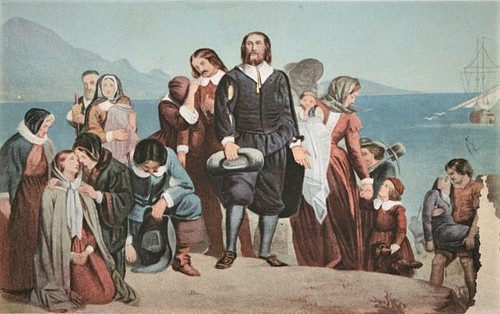

The settlers of Plymouth Colony had arrived off the coast of Massachusetts on the Mayflower in November of 1620 CE and signaled their intention to establish a permanent settlement to the natives by the presence of women and children among them as well as their efforts at building a village. Massasoit would later tell then-governor William Bradford that he had instructed his powwows (shaman) to summon the spirits to drive the new arrivals away but, when this did not happen, decided to try to make peace with them.

Massasoit was interested in this peace because of his diminished status in the region, owing to the loss of a significant number of his people to disease, and the rise of the Narragansett tribe to whom he now had to pay tribute. He hoped, by this alliance, to regain his former power and prestige. The pilgrims, for their part, hoped to establish peace to prevent any hostilities and engage in profitable trade in order to not only make a living for themselves but pay back the investors who had financed their voyage to North America.

The treaty of 1621 CE accomplished both these ends and, contrary to modern-day claims suggesting the Native Americans were taken advantage of by it, was mutually beneficial. It is the only treaty between immigrants and Native Americans from Colonial America (and, arguably, in the history of the later United States) which remained unbroken throughout the lives of the signatories.

Before the Treaty

The natives of present-day New England had been dealing with the arrival of European ships to their shores since at least 1524 CE when the Florentine seaman and explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano (l. 1485-1528 CE) had mapped the eastern seaboard of North America. Verrazzano's map later encouraged attempts at settlement in the region, such as the short-lived English Popham Colony of 1607 CE (in present-day Maine) which lasted only a little over a year. English traders and fishermen regularly came to the area between c. 1610-1614 CE and were at first welcomed until they began kidnapping natives to be sold into slavery. In 1614 CE, Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) arrived to further map the region and left a colleague of his, Captain Thomas Hunt, to finish the business when he returned to England.

Hunt decided to enrich himself by kidnapping 24 natives of the Nauset and Patuxet tribe to sell into slavery in Spain, among them a young Patuxet warrior named Tisquantum (better known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE), who would help Plymouth Colony survive. After being kidnapped, Squanto would later make his way back to North America and, after finding almost his entire tribe had been killed by European disease, came to live with Massasoit, possibly as a captive.

By the time the Mayflower arrived in November 1620 CE, the natives no longer trusted the Europeans, and Massasoit regarded the new arrivals as a significant threat. He sought the guidance of the spirits and divinities of his people in either killing the settlers off or driving them away, but when these efforts produced no results, he thought he might make use of them as allies (possibly after a suggestion by Squanto). Disease had greatly reduced the population of the Wampanoag Confederacy, which had once been the most powerful political entity in the region, and Massasoit had lost his status to the point where he now was paying tribute to the Narragansett tribe (unaffected by the European diseases because they lived further inland) when, formerly, they had been his subjects.

The passengers of the Mayflower (later known as pilgrims after a line in Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation) were equally interested in establishing a peace as they had never intended to land in the area in the first place and were completely on their own. The settlers were a mixed group of Puritan separatists hoping to establish a colony where they could worship freely without the fear of the persecution they had experienced under King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) and so-called Strangers (non-separatists) who were simply seeking to make their fortune in the New World.

They were supposed to have landed in late summer in Virginia, where the English had already established a patent by 1607 CE but, owing to delays, left in September 1620 CE, were blown off course by the fall weather, and wound up off the coast of Massachusetts. Their first encounter with the Nauset tribe, in December 1620 CE, had not gone well, and between December 1620 and March 1621 CE, half the passengers and crew of the Mayflower died of disease and malnutrition. By late March 1621 CE, the settlement still had not been built, most of the passengers continued to live on the Mayflower docked a mile off the coast, and they had little food, having arrived too late in the season to plant any crops.

Samoset & the Pilgrims

As scholar Jonathan Mack observes, had Massasoit only waited, the spirits he had called upon would have answered, and the settlers would probably have died that first year. As it was, however, the chief decided to make first contact with the English and try to form an alliance which would be profitable to them both. He was reluctant to go himself since he was aware of English duplicity and their habit of kidnapping natives without warning. He and his right-hand man, Hobbamock (d. c. 1643 CE), distrusted Squanto because they felt he had been too long among the English and been corrupted so they chose another visitor (or captive) in the village to go as envoy, Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653 CE), an Abenaki chief.

According to the later colonist of Merrymount settlement, Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE), Samoset was a prisoner of Massasoit who, like Squanto, spoke English, which he had learned from European ships in his native region of present-day Maine. Morton claims, in his work New English Canaan (published c. 1637 CE), that Massasoit offered Samoset his freedom in exchange for acting as envoy and Samoset accepted. If the English proved friendly and open to a treaty, Samoset would report back and they would proceed; if the English acted as some had earlier and kidnapped or killed Samoset, Massasoit would know their intentions without having to lose any of his own people.

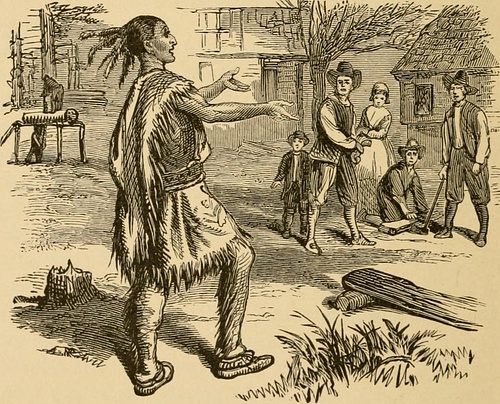

Samoset walked into the settlement on 16 March 1621 CE, welcomed the colonists in English, and was entertained by them for the rest of the day, spending the night in the house of Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644 CE). He explained to them why the natives were wary of them, told them of the kidnapping of many by Captain Hunt and of the diseases which had ravaged the population, and informed them on the area and the relationships of the people who lived there. He left the next day but kept returning throughout the week and, during this time, must have sent word to Massasoit that a treaty looked promising since Massasoit's village was 40 miles away and he arrived near Plymouth Colony before 22 March 1621 CE.

The Treaty is Signed

The account of the signing of the treaty is given first in Mourt's Relation and later, in an abbreviated form, in Of Plymouth Plantation. Mourt's Relation was written by both Bradford and Winslow, but it is unclear who wrote which part. The style of the account of the treaty sounds more like Winslow based on a comparison with his later works, notably Good News from New England (published 1624 CE), but Bradford may have contributed as well. Although the treaty reads as though it favors the settlers, the provisions were understood as applying to both sides even when not specified.

The account is given below as it appears in the 1622 CE publication with modification only in spelling, paragraph breaks, omission of some lines, and parenthetical commentary for clarification:

Thursday, the 22nd of March, was a very fair warm day. About noon we met again about our public business, but we had scarce been an hour together, but Samoset came again, and Squanto, the only native of Patuxet, where we now inhabit, who was one of the twenty captives that by Hunt were carried away, and had been in England, and dwelt in Cornhill with Master John Slaine, a merchant, and could speak a little English, with three others, and they brought with them some few skins to truck, and some red herrings newly taken and dried, but not salted, and signified unto us that their great sagamore [chief] Massasoit was hard by, with Quadequina his brother, and all their men. They could not well express in English what they would, but after an hour the king came to the top of a hill over against us, and had in his train sixty men, that we could well behold them and they us.

We were not willing to send our governor to them, and they unwilling to come to us, so Squanto went again unto him, who brought word that we should send one to parley with him, which we did, which was Edward Winslow, to know his mind, and to signify the mind and will of our governor, which was to have trading and peace with him. We sent to the king a pair of knives, and a copper chain with a jewel at it. To Quadequina we sent likewise a knife and a jewel to hang in his ear, and withal a pot of strong water, a good quantity of biscuit, and some butter, which were all willingly accepted.

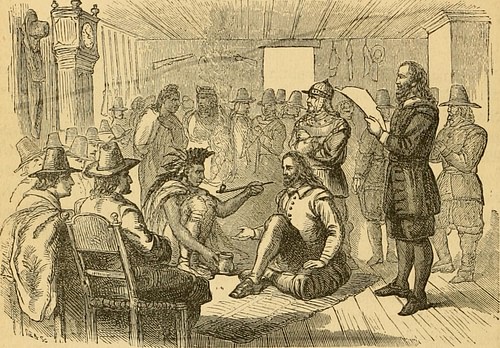

Our messenger made a speech unto him, that King James saluted him with words of love and peace, and did accept of him as his friend and ally, and that our governor desired to see him and to truck with him, and to confirm a peace with him, as his next neighbor. He liked well of the speech and heard it attentively, though the interpreters did not well express it. After he had eaten and drunk himself, and given the rest to his company, he looked upon our messenger's sword and armor, which he had on, with intimation of his desire to buy it, but on the other side, our messenger showed his unwillingness to part with it. In the end, he [Massasoit] left him [Winslow] in the custody of Quadequina his brother, and came over the brook, and some twenty men following him, leaving all their bows and arrows behind them. We kept six or seven as hostages for our messenger; Captain Standish and Master Williamson [a misprint for Thomas Williams, d. March 1621 CE] met the king at the brook with a half dozen musketeers.

They saluted him and he them, so one going over, the one on the one side, and the other on the other, conducted him to a house then in building, where we placed a green rug and three or four cushions. Then instantly came our governor [John Carver] with drum and trumpet after him, and some few musketeers. After salutations, our governor kissing his hand, the king kissed him, and so they sat down. The governor called for some strong water, and drunk to him, and he drunk a great draught that made him sweat all the while after; he [Carver] called for a little fresh meat, which the king did eat willingly, and did give his followers. Then they treated of peace, which was:

- That neither he nor any of his should injure or do hurt to any of our people.

- And if any of his did hurt to any of ours, he should send the offender, that we might punish him.

- That if any of our tools were taken away when our people were at work, he should cause them to be restored, and if ours did any harm to any of his, we would do the like to them.

- If any did unjustly war against him, we would aid him; if any did war against us, he should aid us.

- He should send to his neighbor confederates, to certify them of this, that they might not wrong us, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

- That when their men came to us, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them, as we should do our pieces when we came to them.

- Lastly, that doing thus, King James would esteem of him as his friend and ally.

All of which the king seemed to like well, and it was applauded of his followers…So after all was done, the governor conducted him to the brook, and there they embraced each other and he departed; we diligently keeping our hostages, we expected our messenger's coming, but anon, word was brought us that Quadequina was coming, and our messenger was stayed till his return, who presently came a troop with him, so likewise we entertained him, and conveyed him to the place prepared. He was very fearful of our pieces [muskets], and made signs of dislike, that they should be carried away, whereupon commandment was given they should be laid away. He was a very proper tall young man, of a very modest and seemly countenance, and he did kindly like of our entertainment, so we conveyed him likewise as we did the king, but diverse of their people stayed still. When he was returned, then they dismissed our messenger…

The next morning, diverse of their people came over to us, hoping to get some victuals as we imagined; some of them told us the king would have some of us come see him. Captain Standish and Isaac Allerton went venturously, who were welcomed of him after their manner; he gave them three or four ground-nuts and some tobacco. We cannot yet conceive but that he is willing to have peace with us, for they have seen our people sometimes alone two or three in the woods at work and fowling, when as they offered them no harm as they might easily have done, and especially because he [Massasoit] hath a potent adversary the Narragansetts, that are at war with him, against whom he thinks we may be some strength to him, for our pieces are terrible unto them. This morning they stayed till ten or eleven of the clock, and our governor bid them send the king's kettle, and filled it full of peas, which pleased them well, and so they went their way. (55-59)

Conclusion

After the treaty, Massasoit had Squanto remain with the colonists, teaching them how to plant crops, fish, hunt, and acting as their interpreter in establishing friendly relations and trade with the natives throughout the region. Sometime afterwards, Massasoit also sent Hobbamock, with his family, to live among the settlers, presumably to monitor Squanto as well as the English. Massasoit's distrust of Squanto proved to be justified in that Squanto would later try to play the pilgrims against Massasoit in an attempted coup as Squanto tried to take Massasoit's place.

The plot was revealed through the assistance of Hobbamock, and Massasoit, in keeping with the terms of the treaty, demanded Squanto be handed over for punishment. Bradford refused, since Squanto had become vital to the colony's trade relations with the natives, placing a strain on the treaty. Even so, the agreement was not broken, and the problem was resolved when Squanto died in 1622 CE, possibly poisoned by agents of Massasoit to remove him without endangering the Wampanoag's relationship with Plymouth.

The treaty enabled the colony to survive and elevated Massasoit to his former standing, just as he had hoped. In the course of their early years together, both sides would assist the other in various matters. Massasoit warned the colony of a possible attack by other tribes, Winslow saved Massasoit's life when he became ill and seemed close to death, and trade profited both. Carver died in April 1621 CE, but Bradford continued to honor the treaty as governor throughout his life, and Winslow did the same when he became governor.

The peace established remained firm even during the Pequot Wars of 1636-1638 CE and was only finally broken with the conflict known as King Philip's War (1675-1678 CE) by which time Bradford, Winslow, and Massasoit were dead. It is the only treaty signed between English colonists and Native Americans to have been honored, without modification, throughout the lives of its signatories and established the longest-lasting and most equitable peace between natives and immigrants in the history of what would become the United States of America.