Piracy, defined as the act of attacking and robbing a ship or port by sea, had a long history in the ancient Mediterranean stretching from the time of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) and throughout the Middle Ages (c. 476-1500 CE). Piracy in the Mediterranean remains a persistent threat in the present day only with different kinds of ships and more advanced technology.

Historians sometimes telescope the history of piracy for narrative convenience and wind up implying or even claiming that piracy in the Mediterranean began with the decline of the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BCE and ended when Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) defeated the Cilician pirates at the Battle of Coracesium in 67 BCE when, actually, Egyptian records substantiate piratical activities in the Mediterranean centuries earlier and Roman accounts report its continuance for centuries afterwards.

Piracy was engaged in by governments and was often considered a legitimate act of war. Pirates were not always the “outsiders” flying under their own flag but were frequently employed by governments and were encouraged in their piracy by the slave trade which continued throughout antiquity. Long after Pompey had defeated the Cilician pirates, Rome continued to rely on them for slaves for the empire and, after that empire fell, piracy and the slave trade continued for centuries.

Early Pirates

The earliest evidence of piracy in the Mediterranean comes from the Amarna Letters, the 14th century BCE correspondence between the rulers of various Near East kingdoms and Egypt. In one exchange, the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten accuses the king of Alasiya (in modern Cyprus) of giving aid and support to pirates from the region of Lukka (in Asia Minor) who were raiding his coastal cities. The Alasiyan king denied any involvement and, further, pointed out how the Lukka had raided his own coastal lands and ports.

The Lukka controlled an amorphous region of Asia Minor referenced as the Lukka Lands and are known primarily from Hittite and Egyptian accounts. They may have been Luwians, one of the earliest tribes inhabiting Asia Minor/Anatolia, and they are most likely the same as the later Lycians, also associated with piracy. All that is definitely known about them is that they practiced piracy on a regular basis, were sometimes allies and sometimes enemies of the Hittites, and are named as one of the nationalities who comprised the coalition known as the Sea Peoples.

The Sea Peoples

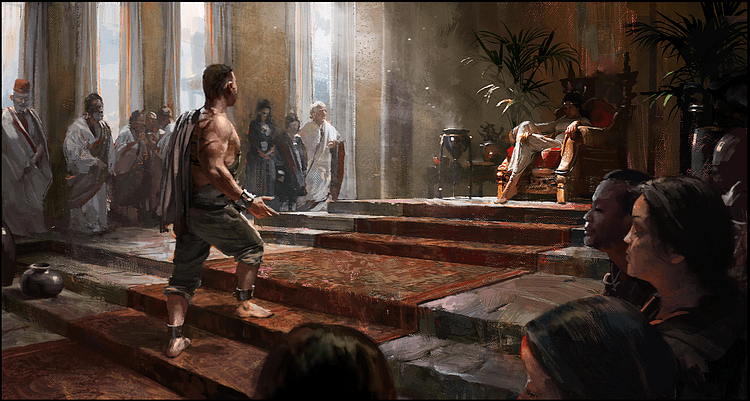

The Sea Peoples were a confederacy of various ethnicities who ravaged the Mediterranean between c. 1276-1178 BCE. Their name is a 19th-century CE designation coined by the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero c. 1881 CE; what they called themselves – if anything – is unknown. Maspero used “Sea Peoples” because the reports of them all claim they came from the sea to attack the coastal cities. They are primarily known from the inscriptions of the three Egyptian pharaohs who defeated them: Ramesses II (The Great, r. 1279-1213 BCE), his son and successor Merenptah (r. 1213-1203 BCE), and Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BCE).

The Egyptian texts record the different groups as the Akawasha, Denyen (Danuna), Lukka, Peleset, Dhardana, Shekelesh, Tjeker, Tursha (Teresh), and Weshesh. Of these, only two have been identified in the present day, the Lukka and the Peleset (Philistines) although the Denyen/Danuna are most likely pirates from the Cilician city of Adana, near Tarsus. Ramesses II records how they came “all at once” and that “no land could stand before their arms” as they “laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth (Inscription from Ramesses II's Temple at Medinet Habu, Bryce, 367). Merenptah adds Libyans to the coalition as does Ramesses III.

The Sea Peoples devastated the region of Anatolia, at the time controlled by the Hittites, and toppled their empire. The last king of Ugarit, Ammurapi (r. 1215-1180 BCE) wrote to the king of Alasiya reporting the Sea People's destruction of his kingdom and how “the enemy's ships came here and my cities were burned and they did evil things in my country” (Bryce, 367). The Sea Peoples are characterized as the first major pirates of the Mediterranean because of the scale of their destruction. Who they were and where they came from remains a mystery.

What is clear is that they were instrumental in the Bronze Age Collapse in the region as well as an increase in piracy and a decrease in trade. They were defeated by Ramesses III in 1178 BCE and, afterwards, disappear from the historical record. Whoever they were, they either established or developed bases – along the southern coast of Cilicia, in Crete, and elsewhere – which would be used by the pirates who came after them.

Pirates & the Slave Trade

Piracy was fueled by the slave trade to such a degree that normally law-abiding sea-traders, such as the Phoenicians, resorted to piracy in kidnapping citizens from coastal towns and ports to be sold as slaves. The slave trade was extremely lucrative. By the time of the Roman Empire, a healthy adult male slave between the ages of 15-40 cost 1,000 sesterces ($3,000.00) and a healthy adult female around 800 sesterces ($2,400.00) while those older or younger would be cheaper (Toner, 21). Slaves might be people taken in conquest or those who sold themselves to escape debt or sold their children for the same reason but they were often people who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and were kidnapped by pirates who then made 100% profit since it cost them nothing to procure the slave other than the effort of hauling him or her aboard ship.

The Tyrrhenians were the most notorious pirates before the age of Rome who were synonymous with the slave trade. According to the Homeric Hymn to Dionysus (c. 7th century BCE and not written by Homer), the Tyrrhenians were not above kidnapping gods to sell into slavery. In the hymn, the Tyrrhenians kidnap a handsome youth and plan on violating and then selling him. They are warned he is the god Dionysus but move ahead with their plan regardless. Dionysus conjures sprawling vines to burst from the boards of the ship and beasts to emerge from them, attacking the pirates, who are then turned into dolphins when they try to escape into the sea. A mosaic depicting this scene (from the city of Utica in the Imperial Age of Rome) is presently housed in the Bardo National Museum in Turin, Italy.

The Tyrrhenians have been associated with the Etruscans of Italy but also with the Tursha (Teresh) of the Sea Peoples in the same way the Denyen (Danuna) are associated with the citizens of Adana. If so (and these associations are far from proven), a direct line is established between the earliest pirates in the Mediterranean and later ones. Even if there is no direct relationship, however, it does not really matter. The basic paradigm of sailing light, agile craft along a coast, seizing ships that could not defend themselves or plundering ports and villages, does not need to have been handed down by some earlier generation; it suggested itself.

The Lure of Piracy & the Illyrians

Pirates who were not members of legitimate trading vessels were most often those who found they could not make a decent living otherwise. The Cilician pirates, for example, were mostly comprised of coastal fishermen in Cilicia Trachea (Rough Cilicia) where the earth was not conducive to farming. When these people felt they were not making a sufficient living from the sea, they turned to piracy either by outfitting their own small boat or joining the crew of one already established.

The typical pirate ship was epitomized in the design of the lembus, a small, agile craft which could easily navigate coastal waters (where the shipping lanes were), intercept and board other vessels, and disappear into coves and harbors inaccessible to larger ships. Any fisherman would have known how to rig and steer a lembus or even build one if they had to.

One need not have been a struggling fisherman to turn to piracy, however. Sea trade and travel could be enticing as it offered the possibility of some kind of upward mobility which one was denied on land as a lower-class farmer, fisherman, or artisan. A member of the crew would have a share in the spoils, could one day perhaps afford one's own ship and crew, and could at least imagine a life more promising and exciting than fieldwork in unrewarding terrain.

Piracy was also considered a perfectly acceptable practice during times of war as long as the action was approved by the state associated with the crew. The Greek orator Demosthenes (l. 384-322 BCE) in one of his speeches notes how three Athenian ambassadors on their way by ship to Caria (in modern Turkey) on a diplomatic mission in 355 BCE had the captain turn the ship around to pursue and intercept a trade vessel out of Naucratis, Egypt. The ambassadors seized the Egyptians' cargo in a blatant act of piracy and then resumed their mission. Demosthenes was not condemning the piracy since Athens was then at war with Egypt; he denounced the ambassadors because they kept the loot instead of turning it over to the state (Demosthenes Against Timocrates, Speech 24.11). As long as one could prove the theft of cargo was against a hostile country, it was not considered 'piracy' but a justifiable act of war.

In an effort to better control Illyria and its pirates, Rome supported Demetrius of Pharos (r. c. 222-214 BCE) as king (who had helped them defeat Teuta) but, as soon as the Romans were distracted, Demetrius rebuilt the Illyrian fleet and returned his people to piracy, thus starting the Second Illyrian War (220-219 BCE). After Demetrius' death, his successors continued to engage in piracy right down to the last king of Illyria, Gentius (r. 181-168 BCE) who started the Third Illyrian War with Rome in 168 BCE and whose defeat led to the destruction of Illyria by the Romans afterwards.

Rhodes & Cilicia

After Illyria, the most active pirates came from ports in Cilicia and Crete. Legend claims that King Minos of Crete was the first ruler to form a fleet to combat piracy during the Minoan Period (c. 2000 - c. 1500 BCE). If so, his descendants veered sharply away from that policy since Crete was a popular haven for pirates by the 3rd century BCE. The Cretan city of Hieraphytna (modern-day Ierapetra) was controlled by pirates who regularly prowled the coasts and islands of the Aegean Sea and into the Mediterranean.

In 167 BCE, the island of Delos was under Roman control and Rome, at odds with Rhodes, sought to undercut their monopoly on trade in the region by making Delos a duty-free port. Rhodes was able to pay for its warships, armed vessels, and patrols through harbor taxes on ships and other duty on cargo. Once Delos became duty-free, more traders began going there and Rhodes could no longer afford to keep up its anti-piracy patrols. Naturally, piracy in the Aegean and Mediterranean seas again flourished and even more so once Roman traders turned Delos into one of the most infamous slave markets in the region. Pirate ships from Melos, Aegina, Crete, and Cilicia now came to Delos with slaves to sell.

Cilician Pirates & Rome

Among those selling slaves were the Cilician pirates, the best known in the present day and the most notorious in their own time. Not all the “Cilician pirates” were from Cilicia as the region's rocky southern coast and many inlets made it naturally attractive to small pirate ships of any nation seeking easy access to harbors they could disappear into and resupply or hide. The Cilician pirates grew in power as the Seleucid Empire, which controlled the coast of Cilicia, began to wane steadily after 110 BCE.

Rome had first become involved in Cilicia in 190 BCE when they took the region from the Seleucids but allowed client kings to continue their rule and ignored the problem of piracy as it did not affect Roman interests. By 103 BCE, however, the problem had grown more serious and Rome sent Marcus Antonius (l. 143-87 BCE, grandfather of Mark Antony) who conquered so-called Smooth Cilicia and then, between 78-74 BCE, sent consul Publius Servilius Vatia (served 79 BCE) who conquered Rough Cilicia but neither did anything to curtail piracy. By 67 BCE, Pompey the Great was in the region campaigning against Mithridates VI of Pontus when he found that Mithridates VI was employing Cilician pirates to interfere with the Roman war effort.

Pompey divided the Mediterranean into 13 districts, assigning a fleet and commander to each. As one district was cleared of pirates (who were captured or killed), that fleet would join another in the next district and, by this process, Pompey drove the Cilician pirates down to the last district off the coast of Coracesium Cilicia where he defeated them in 67 BCE. Pirates were usually crucified, beheaded, or sold into slavery themselves, but Pompey chose the path of rehabilitation and had many of the more promising pirates relocated to central Cilicia where they became productive farmers and members of their communities.

Rome, Pirates, & the Slave Trade

This event is often given by historians as the end of piracy in the Mediterranean but this is simply a convenient falsehood perpetuated by writers following ancient Roman or pro-Roman narratives. After Pompey's victory over the pirates (and later victory over Mithridates VI in 63 BCE), Rome still needed slaves and pirates were still the central agents of the slave trade. Pompey's own son, Sextus Pompey (l. 67-35 BCE) became a pirate and commanded a pirate fleet. Pompey's 67 BCE victory was only a temporary stop-gap which helped win the Mithridatic Wars, not the end of piracy in the Mediterranean. In 31 BCE, the Roman general Octavian defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII at Actium to become Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE), the first Roman emperor. The empire needed even more slaves than the Roman Republic had and so the Cilician pirates were back in business.

The Cilician city of Side (pronounced see-day, modern-day Side, Turkey) was the administrative center for the slave trade in the Mediterranean and became one of the wealthiest because of it. Roman slave traders lavished gifts and money on the city which went to the construction of the monumental gate, the Temple of Apollo, the nymphaeum and baths, and the great theater which could seat over 15,000 people. The ruins of all of these structures and others can be seen in Side today, but the fact that they were built with funds from the slave trade is often overlooked.

Cilician pirates were still plying their trade in the same ways they always had at the time of the writer Pausanias (l. 110-180 CE) who reports on their method of masquerading as legitimate merchants to lure unsuspecting citizens toward their ships. The pirates would announce some quantity of goods they had for sale, wait until a good number of people had either boarded the ship or gathered near to it, and then haul as many as possible aboard and sail away. Unlike earlier, Rome did nothing to stop this practice or curtail piracy in any way because now they were benefiting from it. The Cilician pirates were, in effect, working for the Roman Empire.

Conclusion

Piracy continued in the Mediterranean after the fall of Rome in 476 CE. Pirates continued to provide slaves for the Byzantine Empire and then Arabian fleets of Muslim pirates appeared after the 7th century CE, kidnapping Greek and Roman citizens for the slave markets in their own towns and cities. During the First Crusade (1096-1099 CE), European pirates helped the Crusaders harry the coasts of the Holy Land and Muslim pirates disrupted European ships arriving with supplies. The Frisians (of modern-day Netherlands) acted as pirates during the Fifth Crusade (1217-1221 CE), and other nations did the same.

Piracy continued in the Mediterranean for the same reasons it always had: because it was a way to make a great deal of money and provided one with the opportunity for upward mobility, travel, and excitement, and all at someone else's expense. To the pirate mentality, there was no reason to struggle to make a living when one could more easily steal a living from others; and this is the same reason why piracy – of whatever – kind continues to thrive in the present day.