Plebeians were members of the plebs, the hereditary social class of commoners in ancient Rome. Their exclusion from political power by the patricians, who claimed to be the descendants of the first senators, led to Conflict of the Orders, a centuries-long struggle for equal political rights for plebeians, which saw the creation of the Twelve Tables and other laws.

Social Structure in Early Rome

From the days of the Roman monarchy (753-509 BCE) and throughout the early Roman Republic, the Roman political and social structure was divided into two distinct classes or orders: the patricians and the plebeians (plebs). Although there is some dispute, the city's legendary founder and first king, Romulus, was said to have created both the Roman Senate and the Centuriate Assembly (Comitia Centuriata), with the latter enacting laws. The patricians professed themselves to be descendants of the city's original fathers – the first senators appointed by the king – and claimed the exclusive right to rule, thereby disallowing the plebs any access to power. Although some give him credit for its creation, the legendary sixth king, Servius Tullius (578-535 BCE), reformed the Assembly, organizing it into voting blocs or centuriae (blocs of one hundred). Combined with one's accident of birth, the reorganization of the Centuriate Assembly would further deny the plebs any voice in the government.

Historian Simon Baker in his book Ancient Rome wrote that the patricians were able to justify their complete monopoly on power through Rome's strict religious beliefs. Religion, he said, was of critical importance to all Romans, and they believed the success of the city was wholly dependent on the approval of the gods. The patricians claimed the priesthoods, and because they believed they had special knowledge of the gods, they alone were best qualified to hold all political offices. This exclusive knowledge would, therefore, bring favor to Rome. Of course, the plebeians completely disputed this claim.

Throughout the monarchy, because of their ancestry, the plebs was denied access to any political office or the priesthood. Although they had no political power, being a plebeian did not necessarily imply that an individual was poor. While many of the plebeians were poor farmers, others were prosperous merchants and rich landowners. After the fall of the monarchy in 509 BCE and the expulsion of the last king, the patricians maintained their tight control of the government: the Senate, the Centuriate Assembly, and, most importantly, the election of the consuls.

Plebeians Rise Up

As one might expect, this unfair division of power caused considerable tension between the two orders. In his book The Storm Before the Storm, Mike Duncan wrote that this conflict between the patricians and plebeians defined the early Republic. After the founding of the Roman Republic, the plebs continued to resent being denied access to any political office. Mary Beard in her book SPQR wrote of the plebs' feelings of exclusion and exploitation:

Why fight in Rome's wars …when all the profits of their service lined patrician pockets? How could they count themselves full citizens when they were subject to random and arbitrary punishment, even enslavement if they fell into debt? (146)

Within two decades of the Republic's birth, the plebs decided to rise up against the abuses of the patricians and force concessions. The result was to stage a walkout – the first in a number of such protests – that became known as The Conflict or Struggle of the Orders.

Prior to the Roman expansion across the Mediterranean Sea and their dependence on allies to fill the legions of the military, the Roman army relied heavily on the plebs to fight in their military conflicts. In 494 BCE, the plebeians, many of whom were poor farmers and mired in debt, refused to answer the call to serve in the army when Rome's borders were being threatened. Many of them were unable to maintain their farms while serving in the army and were forced to turn to the patricians for assistance, which led to their indebtedness and possible imprisonment. Together, the plebs exited Rome (although many of the richer plebeians remained in the city), gathered on Aventine Hill, and demanded concessions, vowing to remain outside the city until their ultimatums were met.

The patricians soon realized their dependence on the plebs and submitted to their demands. Negotiations began between the plebeian leadership and the moderate former consul Gaius Menenius Agrippa and other senators, and the strike (some call it a mutiny) saw the beginning of a change in the balance of power.

Plebeian Assembly & Tribunes of the Plebs

Several concessions were made to satisfy the plebeian demands. The first concession came in the creation of the Concilium Plebis or the Council of the Plebs, which initially only represented the concerns of the plebeians (ius auxilii) against patrician abuse, but its authority gradually increased over time. The assembly enacted laws and elected two officials or tribunes of the plebs (tribuni plebis); this number later increased to ten. One of the first two tribunes elected was Lucius Sicinius Vellutus, the individual who had led the walkout to Aventine Hill. The second one elected Lucius Junius Brutus (no relation to the future consul).

Each plebeian was required to take an oath to support the decision of the tribune whose power gradually increased, eventually becoming inviolable under the sacred law (lex sacrata), in a concept known as sacrosanctity (sacrosanctitas). He could summon the Plebeian Assembly to convene, elicit plebiscites (laws), and veto any magistrate or even another tribune's decision (intercessio) that pertained to the plebs. The tribune even had the authority to interfere physically (auxilium) to defend a citizen who was being wrongfully punished or oppressed. According to Anthony Everitt in his The Rise of Rome, "He could fine, imprison, or execute anyone who challenged his authority, or even, badmouthed him" (96).

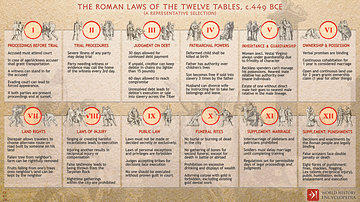

The Twelve Tables

At the time of the first walkout, the Romans had no written constitution. Instead, they had unwritten rules and traditions (mos maiorum), or "the way of the elders." The plebs demanded the patricians make the laws public. This demand led to another concession: the Twelve Tables of 450 BCE. In 451 BCE, ten men, the decemvirs with consular power (decemviri consulari imperio legibus scribundis), had gathered together to collect, draft, and make public the laws. This first decemvirate wrote ten tables, and two years later a second decemvirate convened and added two more tables. One of these new laws prohibited the marriage between a patrician and a plebeian, however, this rule would be overturned later.

The Twelve Tables were displayed in the Roman Forum. Some historians contend this to be the starting point of the development of Roman law. In further concessions, the plebs was guaranteed no imprisonment for debt and the right to appeal the decisions of the magistrates (provocatio ad populum). Over time, after additional pressure, more laws were passed and, most importantly, the decisions of the Plebeian Assembly became binding to the patricians.

The voice of the plebs would also be heard in the increased power of the Tribal Assembly (Comitia Tributa). For years, the assembly was controlled by the wealthy; however, after the Conflict of the Orders, the assembly was reclassified into 35 districts or tribes. Four of these tribes were in Rome while the remaining 31 were in the rural areas. The assembly enacted laws and appointed quaestors, military tribunes, and curule aediles. Each tribe contained both poor and wealthy, thereby becoming more representative.

Conclusion

It took the plebeians almost two centuries to achieve equality with the patricians. By 367 BCE, the plebs could stand for election to consul, and by 366 BCE, the first plebeian consul was elected. In 342 BCE, it became law that one of the two consuls had to be a plebeian. By 172 BCE, the plebs had held both consulships. Mary Beard wrote:

[The Conflict of the Orders] had done something far more significant and wide-ranging than simply end political discrimination against the plebeians. It had effectively replaced governing class defined by birth with one defined by wealth and achievement. (167)

Although there are those who question the historical accuracy of the Conflict of the Orders of 494 BCE, the final acquisition of power made the plebs an integral part of the political system. In Beard's words, "The history of the Conflict of the Orders adds up to one of the most radical and coherent manifestation of popular power and liberty to survive the ancient world" (150).