Plutus (aka Wealth) is a play written by the great Greek comedy playwright Aristophanes in 388 BCE. It was the last of his plays to be performed during his lifetime. Like his earlier play Ecclesiazusae (The Assemblywomen), Wealth was written after the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War. Although the war was basically over, the city of Athens still suffered both economically and politically. The play centers on the status and poverty of everyday people. Aristophanes main character Chremylus, a poor Athenian, and his slave Carion are returning to the city from the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi when they meet a blind old beggar, identified later as Wealth. Upon returning to Athens with a reluctant Wealth, the social and economic structure of the city quickly changes, poverty and injustice quickly disappear. Riches are doled out to the deserving, but, unlike in his earlier plays, the rich in Wealth are not seen as virtuous and many of them lose their fortunes.

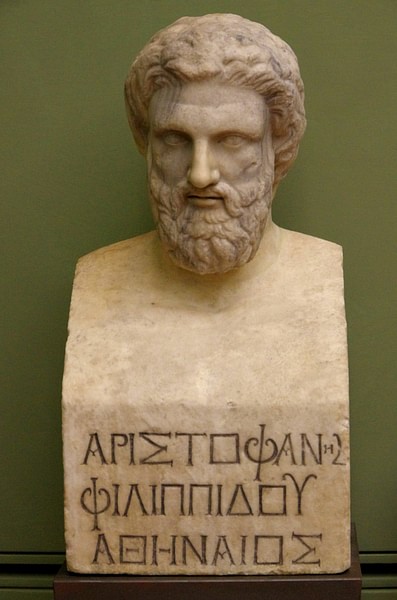

Aristophanes

Very little is known of Aristophanes' early life; even his birthdate is unclear. Since most of his plays were written between 427 and 386 BCE, it helps place his death around 386 BCE. A native of Athens, he was the son of Philippus and owned land on the island of Aegina. He had two sons, one of whom became a playwright of minor comedies. Although participating little in Athenian politics, Aristophanes was an outspoken critic, via his plays, of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and those politicians who supported it. His portrayal and attack of the statesman Cleon in the play The Babylonians landed him in court in 426 BCE. Aristophanes opposed all changes in the traditional aspects of philosophy, education, poetry, and music. Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity said the playwright reflected the conservative opinion of many Athenians, showing them to be people who valued old simplicity and morality.

By the time Aristophanes began to write, Greek theater was in serious decline. Although Aristophanes is sometimes condemned for bringing drama down from the high level of the Greek tragedy written by Aeschylus, his plays, with their simplicity and vulgarity, have been recognized and appreciated for their rich fantasy as well as humor and indecency. Editor Moses Hadas in his book Greek Drama wrote that while Aristophanes could write poetry that was both delicate and refined; however, he could also, at the same time, demonstrate bawdiness and gaiety. To many his comedies were a blend of wit and invention. Unfortunately, with only eleven of his plays surviving, Aristophanes' works from this period are the only known examples of Old Attic Comedy to exist.

Synopsis

Chremylus, a poor Athenian, and his slave Carion are returning home from the oracle at Delphi. He was told to take the first person he meets on the road to his home and that person happens to be an old blind beggar, later identified as Wealth. The old man reveals that he had been blinded by Zeus so he could not tell the just and wise from the bad. Hoping to help his own situation, Chremylus promises to help him restore his eyesight. Soon, the old beggar's presence at the home of Chremylus draws the attention of many of his friends and neighbors. One of them is Poverty who chides Chremylus and his friend Blepsidemus and tells them they are all doomed and promises to make them pay for their schemes.

As promised, Wealth is taken to the temple of Asclepius the Healer to regain his eyesight. Upon returning home, people gradually appear to thank Wealth for their “blessings.” However, many of the rich also appear to show their disdain. Hermes, the messenger god, arrives and tells them that Zeus is angered because people no longer sacrifice to the gods. A priest appears and vows to abandon Zeus for Wealth. Chremylus decides to reinstate Wealth as the guardian of the treasury at the temple of Athena.

Cast of Characters

The rather long cast of characters includes:

- Carion

- Chremylus

- Wealth

- Chorus of farmers

- Blepsidemus

- Poverty

- Chremylus' wife

- a good man

- an informer

- an old woman

- a young man

- Hermes

- a priest

- a slave

- a witness

Plot Summary

The play opens on a street in Athens. Chremylus and his slave Carion are following a dirty old beggar soon to be identified as Wealth. Carion and his master have just come from the oracle at Delphi and are still wearing their laurel wreaths. Carion asks aloud:

Master, I insist on your telling me why we're following that man. If you don't, I'll just keep on asking and asking and asking. (272)

Somewhat avoiding the question, Chremylus replies that he is a poor man, pious and upright “while temple robbers, politicians, informers, wicked men of all kinds have become very rich” (273). He reminds Carion that they went to Delphi for his only son, wondering whether he should become a criminal or villain because it is the only way to get ahead in life. He tells Carion that Apollo told him to take the first person he sees coming out of the temple home. They slowly approach the old man who continually protests, only wanting to be left alone. Finally, after they physically grab him, he tells them:

I was going to keep my identity a secret but since I've no choice but to reveal it. My name is Wealth. (274)

Explaining his blindness, he informs them that in his youth he would only serve the upright and wise and modest but Zeus made him blind so that he could not know the difference. Chremylus says it is only the good and upright who honor the god and promises to restore the old man's eyesight. Wealth is reluctant, fearing what Zeus might do to him if his sight is restored. He is told that he could depose Zeus if he chose to, for Zeus could easily be overthrown if people stopped making sacrifices to the gods.

...you've got far more power than Zeus...Everything in the world is controlled by wealth...You alone are responsible for everything, be it good or evil. (275-7)

As Chremylus and Wealth arrive at his home, he instructs Carion to round up his farmer friends. The two men enter Chremylus' home as Carion speaks to a gathering of local farmers:

My master says that you will now be able to free yourselves from your old, cold dissatisfied life and pass your day in happiness. (280)

Reluctantly, he tells them that Chremylus has brought home Wealth, and he is going to make them all wealthy. As his friends arrive at his home, Chremylus greets them. Although some are accepting of the news, his close friend Blepsidemus is doubtful, suspicious of his friend's new-found riches. Chremylus tells them all that plans are in place to take Wealth to the temple of Asclepius where his eyesight will be restored and if they are successful there will be permanent prosperity. As they speak, an old woman, dressed completely in black, appears. It is Poverty. She speaks to both men:

I shall destroy as befits your evil scheme. You are venturing on an utterly intolerable course of action…. You are doomed. (285)

She introduces herself as Poverty, their constant companion. She asks them who will build their ships, make their bricks, do their laundry, or harvest the fruits. Blepsidemus calls her “the most vicious pest the world has ever bred (286)” Chremylus tells her that restoring Wealth's eyesight will kick her out of Greece. Poverty claims that she, not Wealth, is responsible for all the good things in life. All modesty and decency belong to her:

You don't realize that I give you better men than Wealth ever can, better in body and better in mind. (289)

As she leaves, she tells them that they will one day beg to have her return. They decide it was time to take Wealth to the temple and be healed. The next day Carion announces that Wealth is no longer blind; it is a time for joy. Chremylus' wife comes out of the house; she is told the good news. He tells her of the previous night's stay at the temple and the people who were there seeking help. After Wealth was given a bath, his eyes were wiped with a clean cloth. Next, a red cloth had been placed over Wealth's eyes, snakes came out and licked his eyes, and upon the cloth's removal, he could see. Shortly wealth returns to Chremylus' home:

I am heartily ashamed of my previous experience, thinking how I unwittingly associated with wicked men and ignorantly shunned those who were worthy of my company. (297)

Soon, a number of people gather at the house to speak to Wealth, some thankful and some angry. A man, identified only as Good Man, arrives at the house. He has come to thank Wealth for the blessings he has been given; he has passed from misery to bliss. Unfortunately, a second man, simply called Informer, comes to express his contempt, for he has been ruined, robbed of everything. An old woman and her slave arrive at Chremylus' home; she has been treated horribly, disgracefully and illegally. She speaks of a young man who 'loves' her. She treats him well, giving him whatever he wants, but now he has changed his mind, returning all of her gifts. The young man arrives, hurling a few insults at the old woman. She reprimands him for treating her like dirt. They all enter the house together.

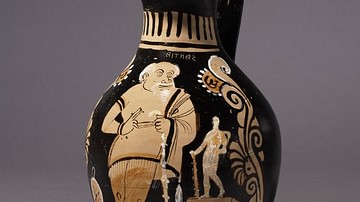

Hermes, the messenger god, knocks on the door. He tells Carion that Zeus is angry and “intends to mash up the whole lot of you in one dish and hurl you into oblivion.” (307) Nobody is sacrificing to the gods. “No incense, no laurel, no barley cakes, no animals, no nothing.” (308) Hermes is troubled; his own life is ruined, so Chremylus offers him the chance to join them; he can be the 'God of Competitions.' Carion calls him the 'Divine Servant.' A priest of Zeus appears and asks to speak to Chremylus, complaining that he is almost dead of starvation as no one bothers to sacrifice at the temple. Finally, he has decided to abandon Zeus and stay with Chremylus and Wealth. Plans are put into place to restore Wealth in his treasury chamber at the temple of Athena. They all form a procession and march to the temple, even the old woman.

Analysis

With the war against Sparta finally over, Aristophanes relaxed his anti-war fervor and turned his attention to the economic and political instability of Athens. In his play The Assemblywomen he dealt with the political aspects of the crumbling city. In it, the control of the city's government was given over to the women; something that had never been tried before. At the end of the play success had apparently been achieved. In Wealth he considered the economic plight of post-war Athens and the extreme poverty of the common people. The city's farmers were hard pressed. Poverty, portrayed as an old woman dressed in black, was many people's constant companion. Aristophanes portrays the rich, often viewed as virtuous, to be angry and bitter at the loss of their wealth. Religion also comes under scrutiny. With wealth everywhere, no one makes sacrifices to the gods. Hermes, the messenger of the gods, abandons Zeus and joins Chremylus and Wealth as a servant. Lastly, a starving temple priest forsakes his duties and marches along with the others to restore Wealth to the official duties at Athena's temple.