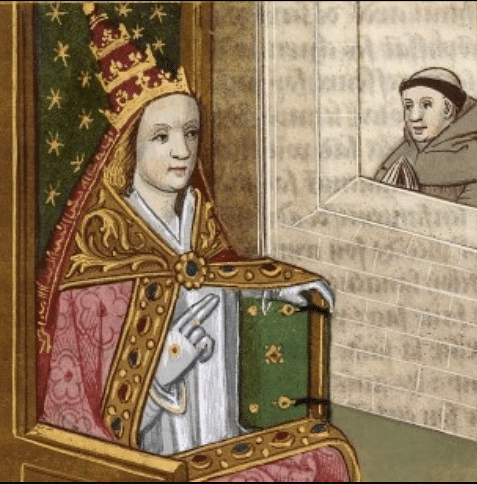

Pope Joan was a legendary female pope of the Middle Ages said to have reigned from 855 to 858. After her story was popularized by Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), a statue of her was placed alongside those of other popes at Siena Cathedral. During the Reformation, her status was a focus of controversy.

When Czech reformer Jan Hus (1372 – 1415) discussed the story at his trial before the Council of Constance, none of the assembled elite of the church questioned it. Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) claimed to have seen a statute of Joan when he visited Rome in 1510. Luther and John Calvin (1509—1564) both used Joan to dispute Catholic doctrine. Her statue was removed from the cathedral after the story was questioned by French writer Florimond de Raemond (1540– 1601).

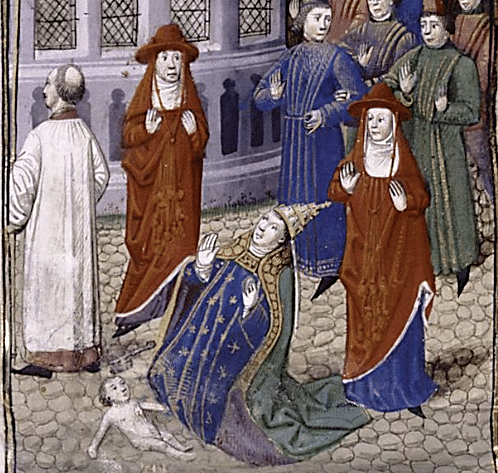

According to the legend, Joan was born of English parents in the German city of Mainz. She travelled to Athens with her lover and disguised herself as a man to receive a religious education. She distinguished herself as a scholar and rose up the ranks of the church. In 855, she was unanimously elected pope by the College of Cardinals. She was exposed as a woman and an adulteress when she unexpectedly gave birth during a procession.

Jean de Mailly

The earliest surviving account of Joan’s papacy is in the Universal Metz Chronicle written in 1255 by Jean de Mailly. Jean was a Dominican in Metz, Lorraine.

To be verified: About a certain pope, or rather a popesse, for it was a woman. Pretending to be a man he was made a notary of the curia on account of the uprightness of his character, and then cardinal and finally pope. On a certain day, when he had mounted a horse, he gave birth to a child and immediately by Roman justice had his feet tied together and was dragged by the tail of the horse and was stoned by the people for half a league and where he died, he was buried, and it was written there: Peter, Father of Fathers, Publish the Parturition [childbirth] of the Popesse [Petre, Pater Patrum, Papisse Prodito Partum]. Under him was instituted the fast of the Four Times, called the fast of the Popesse. (Noble, 220)

Although Jean does not give us the name of the pope in question, the text points us to an inscription on a tomb or a monument somewhere in the vicinity of Rome. Perhaps he had a friend of a friend who took a pilgrimage and noticed this inscription. Latin inscriptions used initials, so this one would be PPPPPP. The original meaning may have been something unrelated to popesses. A wit spun it as a reference to a female pope giving birth, thereby inspiring the legend of the great popess who never was.

The phrase "father of fathers" is associated with Mithras, whose cult was prominent under Emperor Diocletian. If the original monument was a plinth for a statue of Mithras, the inscription could have been, “Have mercy, father of fathers, paid for with his own money.” (Parce, pater patrum, pecunia propria posuit). (Noble, p. 226)

“The fast of the Four Times” refers to the Ember Days, namely St Lucy's Day (13 December), the first Sunday in Lent, Pentecost, and Holy Cross Day (14 September).

Martin Strebsky

The version of the story that was most widely accepted as historical was given in Chronicle of the Roman Popes and Emperors, written by Martin Strebsky of Troppau. The entry on Joan first appears in the 1277 edition. Strebsky was a Dominican in Prague and a papal chaplin:

After that Leo [that is, Leo IV], John, an Englishman, born in Mainz, reigned for two years, seven months, and four days. He died in Rome and the papacy was vacant for a month. He, as is said, was a woman, and when she was still a girl she was taken to Athens dressed as a man by a certain lover. She advanced so much in various branches of knowledge that no one could be found to equal her. Subsequently she taught the trivium in Rome and had great teachers as her disciples and auditors. And because her life and learning were held in high repute in the City, she was elected pope unanimously. But while pope she was impregnated by her lover. Not knowing the time of her delivery, when she was headed from St. Peter’s to the Lateran, she gave birth in a narrow passage between the Coliseum and San Clemente and, after her death, as is reported, she was buried in that very place. Because the lord pope always avoids that street it is believed by many that he does this on account of his detestation of that event. He is not placed in the catalogue of the holy pontiffs on account of the deformity of the female sex as it applied to this matter. (Noble, 222)

Strebsky gives us a second basis for the story, an allegedly shunned street between the Colosseum and the St. Clement’s Church. This church is built on a mithraeum, a cave once used for the worship of Mithras. This street was blocked for a time in the Middle Ages, which may explain the papal detour.

That both Jean and Strebsky were Dominicans may be significant. The order refused to turn over a priory in Genoa to the family of Pope Innocent IV (r. 1243-1254). In 1254, the pope retaliated with a decree restricting the rights of Dominicans to preach and hear confessions. The Dominicans recited litanies and the pope suffered a stroke and died a few weeks later. This led to the expression, “Beware the litanies of the Dominicans.”

Strebsky tells us that Joan studied in Athens. In the 9th century, the city was overrun by barbarians and had no schools. The author may have been thinking of Agnodike, a legendary Greek woman who dressed as a man to study medicine in Athens in the 4th century BCE.

Boccaccio

Florentine writer Boccaccio produced the version of Joan’s story that people of the Middle Ages were most likely to be familiar with. In Concerning Famous Women (1362, De Mulieribus Claris), he placed her alongside goddesses and other mythical figures, so there is no attempt to hide that the story was fiction, or at least fictionalized. “Joan, an Englishwoman and pope,” is how Boccaccio described her. She was, “Spurred by the devil who had led her into this wickedness and made her persist in it.” (231-232)

All the same, Boccaccio was not unsympathetic to Joan. She “had a good mind and was attracted to the charms of learning” and she was “very virtuous and saintly.” She was “deemed to have excelled all others” and she “lectured on the trivium,” the medieval version of being a high school teacher. (231-232) This pattern of lavish praise alternating with passages that revel in a subject’s humiliation is typical of how Boccaccio dealt with female subjects. Around 1400, Boccaccio’s story was popular enough to get Joan recognized as an official pope with her own statue at Siena Cathedral.

Reformation

When Protestants questioned the authority of the pope during the Reformation, Catholics responded by appealing to the doctrine of apostolic succession. This is the idea that the pope’s authority is confirmed by an unbroken line that goes back to Peter. Rome is one of three apostolic sees, along with the churches of Antioch, also founded by Peter, and Alexandria, founded by Saint Mark.

A woman pope would seem to run afoul of several biblical injunctions. “And I do not permit a woman to teach or to have authority over a man,” Paul wrote to Timothy (I Timothy 2:12, NKJV). “Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you,” God told Eve (Genesis 3:16). Yet Timothy himself was taught by his mother Eunice and by his grandmother Lois. Deborah was a prophetess and a judge of Israel, and she defeated the Canaanites guided by God rather than by her husband: ”The Lord will sell Sisera into the hand of a woman." (Judges 4:9)

”Was not the church without a head and without a ruler during the two years and five months Joan occupied the See of Rome?” Hus asked at the Council of Constance in 1415. (Stanford, Chapt. 10) He went on to use Joan as an example of sin and error. Mere election cannot be enough to make a pope, Hus argued. You had to be worthy. The council wasn’t impressed. It condemned Hus to death. If there had been a female pope, there could not be an unbroken line of succession, according to both Luther and Calvin. Even if one ignored the male heretic popes, one couId never, “leap over Popess Joan,” as Calvin put it. (Rustici, 40)

According to one story that is really too good to check, Joan inspired the church to add a ritual to the papal crowning ceremony to prevent another female candidate from escaping detection. The popes were crowned on an enormous purple marble chair called the Estercoraria Chair. This chair had an opening like a toilet that allowed a cardinal to verify that a new pope was really male. After the examination, he would announce, "Duos habet et bene pendentes." (He has two and they hang well.)

Debunking the Myth

Bordeaux magistrate and writer Florimond de Raemond debunked the story of Joan, at least as far as Catholics were concerned, in Erreur Populaire. The first edition published in 1587 was forty pages long. Enlarged editions were published in 1588 and 1594, suggesting enormous public interest in this subject. Florimond showed that a 1082 chronicle by Marianus Scotus had been altered to include a reference to Joan. This meant that the earliest authentic reference was four centuries after the purported event. As for the story of the perforated chair, it was “so gross” that the only appropriate response was to laugh, Florimond wrote. (Tinsley, 391) He campaigned against the statue in Siena, which was removed in 1601 and replaced by one of Pope Zachary (r. 741 – 752).

Among Protestants, Florimond’s efforts only backfired. The 200-page 1594 edition found its way to distant lands, including England. It gave the Siena statue attention it might not otherwise have received. The statue’s removal led to the suspicion that Catholics were destroying evidence. With her own legitimacy as a female ruler questioned, the reign of Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603) was perhaps not the right time to bring this issue up. John Jewel, the bishop of Salisbury (1560-1571) wrote pamphlets that made Joan part of official anti-papal propaganda.

French protestant clergyman David Blondel (1591-1655) wrote a thesis debunking Joan in 1647. Few Protestants were ready to listen in Blondel’s own time, but he got a rave review from British historian Edward Gibbon a century later. Pope Joan “was annihilated by two learned protestants, Blondel and Bayle,” Gibbon wrote in 1776. For Gibbon, the fact that the story is repeated in so many manuscripts shows that it was considered extraordinary, and it is therefore less believable. “The advocates for Pope Joan produce one hundred and fifty witnesses, or rather echoes, of the XIVth, XVth, and XVIth centuries,” he wrote. (Gibbon, Vol. 8, Chap. XLIX.)

Pope Leo IV reigned from 847 to 855 while Benedict III reigned from 855 to 858, leaving no gap for Joan, according to Noble. There is a coin with Benedict on one side and Frankish Emperor Lothar I on the other. This means that it was issued when both men were reigning. Lothar died in September 855, so the coin confirms that Benedict was pope that year.

Tarot

The popess card in the tarot deck naturally brings Pope Joan to mind. The original card was part of a deck produced for the Visconti-Sforzas, the ruling family of Milan, in the mid-15th century. The cards in this deck are unlabeled, but the woman resembles images of Mother Church that were common at the time. (“"Papesse" as an allegory”)

The name popess comes from Jean Noblet’s deck of 1650. The name makes her card complimentary to the pope card. Jean Dodal’s deck of 1701 gives this card as “La Pances” (the belly). This refers to the expectant mother of Revelation 12:1-2, interpreted as Mother Church. In the Rider-Waite deck of 1909, the card is inscribed “high priestess.” But the crescent moon under her feet is from Revelation.

Enduring Interest

For over 700 years, Joan has been a popular subject with one generation of writers after another. Protestant writers used Joan to undermine the authority of the papacy. In the Enlightenment, she represented medieval backwardness and superstition. In the romantic 19th century, she represented joyous liberation from traditional roles, according to Noble.

A film version of Joan’s life released in 1972 was directed by Michael Anderson and starred Liv Ullman. It received horrendous reviews. In 1996, Donna Woolfolk Cross revived the tale with the novel Pope Joan. In 2009, German director Soenke Wortmann made a film based loosely on Cross’s novel. (Germany has always been at a center of the cult of Pope Joan.) Boccaccio explained Joan’s crossdressing as motivated by her desire to follow her lover and “assuage her lecherous ichings.” After he died, she went to Rome to use her learning as a teacher and later as curial notary. In contrast, the film shows Joan adopting male dress for personal safety after a Viking raid.

No longer a sex-crazed villain, a modern Joan heroically rises to the top in the face of misogyny. Her prominence today is not what it was in the 19th century. But she still ranks among the top ten popes in terms of mentions on Google Books, overshadowing the vast majority of the 266 real popes.