Poverty Point is an archaeological and historic site in Louisiana, USA, dated to c. 1700-1100 BCE, enclosing one of the most significant Native American mound sites from Pre-Colonial America. It was once the location of a grand complex of residential homes built on platform earthen C-shaped ridges facing a central plaza with a ceremonial mound and other mounds surrounding the ridges.

The construction of the site suggests a belief in sacred geometry in which shapes focus spiritual power and offer protection. The C-shaped ridges suggest a circle (and some archaeologists have suggested they continued on into the area now occupied by a river and formed a circle until washed away) while the placement of the outer mounds suggests a square.

The site was long thought to be the oldest mound complex in the United States before the discovery in the 1980’s of the site known as Watson Brake in roughly the same area which has been definitively dated to c. 3500 BCE. The name of the original inhabitants is unknown, and the modern name is derived from that of the 19th century plantation the mounds were located on when discovered.

No one recognized the ridges as artificial constructs until the 1950’s (by which time they had been repeatedly plowed for crops), although the site was understood to have been a Native American community as early as the 1830’s and excavations were initiated as early as 1913 by the famous C.B. Moore (l. 1852-1936) who investigated a number of other Native American mound sites. Interest in the site grew in the 1950’s and Poverty Point was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014, preserving the site while allowing for ongoing archaeological work.

Archaic Period & Mound Building

Poverty Point was built during the Archaic Period (c. 8000-1000 BCE) when many mound sites began to proliferate throughout North America. Archaeologist Joe Saunders, who has worked at this site and many others, comments:

During the five-thousand-year span of mound creation, there were two cycles of building and stasis. The first stasis lasted for one thousand years, between the end of the Middle Archaic (2700 BCE) and the beginning of the Poverty Point (1700 BCE) periods. The second lasted about five hundred years, between the end of the Poverty Point (1200 BCE) and beginning of the Tchefuncte (500 BCE) periods. Although mounds were not being constructed during either stasis, campsites dating to each period have been found. Indigenous people continued to live in the lower Mississippi Valley; they just apparently didn’t build mounds then. (1)

The reason for the periods of near-constant construction and those of stasis are unknown and it is also unclear as to why the mound-building was initiated in the first place. Although mounds were constructed by many different cultures across the continent the two best known for the number of sites built are the Adena Culture (c. 800 BCE-1 CE) and the Hopewell Culture (c. 100 BCE-500 CE) both of the period known as the Mississippian Culture which is usually, but not always, dated to c. 1100-1540 CE. The names of all these cultures are modern-day designations and the period of the so-called Mississippian Culture is more fluid than is usually suggested by scholarly dating.

Archaeological dating of mounds is always dependent on what has been discovered and excavated thus far and so rigid periodization is unhelpful as it creates an artificial narrative of “development” from one era to the next when, in reality, the Native American cultures that created the mound sites all maintained their own traditions which cannot be compared as more or less “advanced” than others.

Watson Brake

An example of this is the discovery of the site known as Watson Brake in the 1980’s. Prior to this discovery, Poverty Point was considered the oldest mound site in North America and archaeologists dated cultural progression from c. 1700 BCE. Watson Brake, however, dates to c. 3500 BCE and its discovery opened up a whole new vista of mound building, pushing it back much further than previously understood. Native Americans had been living on the continent for thousands of years, possibly as early as 40-50,000 years ago, and in that time developed their different cultures which eventually found expression in monumental building projects. That much is known but the definition of “development” or “advances” is often an individual interpretation. The “advances” of Poverty Point were considered certainties until the discovery of Watson Brake.

Watson Brake is comprised of eleven mounds connected by ridges built by a hunter-gatherer society that put down permanent roots in the region of present-day northeast Louisiana and raised the site. The purpose of the mounds and ridges is unknown as they were not used for burial, religious rituals, or for residences. Saunders comments:

Mounds exhibit a variety of forms, but conical, dome, platform, and effigy mounds are most common. Some mounds were built in a single episode, while others had multiple stages of construction. Conical mounds tend to be older than platform mounds, but structures were more common on platform mounds. Contrary to popular belief, not all mounds contained human burials nor were they built as high-water refuges. In fact, the first mound builders constructed their earthworks where flooding did not occur. There does not tend to be a singularity of purpose to mound building other than the act itself. It is reasonable to conclude that building earthworks was a communal effort that involved planning, engineering, and organizing labor. (1)

This paradigm is evident at Watson Brake where the mounds appear to have been raised for their own sake. Even so, it is possible there was a ritualistic purpose to the design and construction of the site which simply has not yet come to light. The site, like many Native American mound sites, is only partially excavated. Mounds at other sites, and sometimes whole sites themselves (such as Pinson Mounds), were dedicated to ceremonial, religious rituals which honored the gods, spirits, and ancestors of the people.

Native American Religion

Native American spiritual beliefs took the form of animism – the understanding that all living things are imbued with a spirit and are interconnected – and artifacts discovered at mounds throughout the United States suggest a common purpose of mound-building was to focus spiritual energy at a central location. At Moundville, for example, the homes of the elite were all built on mounds facing a central mound in the middle of a plaza and that central mound itself was astronomically situated and, further, seemingly built to honor all four elements of earth, air, fire, and water. Scholar James Wilson comments:

The common thread running through every level of East-coast society and every aspect of Indian life was the ubiquitous belief in `power’. Although – with a few exceptions - [chiefs] were not themselves shamans, they shared the vision of a world shaped and interpenetrated by potent numinous forces…in a universe where every human act has spiritual ramifications and can affect the well-being of the people, there is no clear-cut boundary between `sacred’ and `secular’… [Their world was] a series of bilateral, reciprocal relationships: between men and women; between families, between humans and the realm of spirits. Contacts and movements between these different spheres had to be mediated through rituals and gift exchanges which acknowledged the respective positions of the two sides and committed them to fulfilling their mutual obligations. (53)

These rituals were performed at sacred sites – places where potent spiritual energies could be identified – and this, it is thought, directed where and how mounds were built. The energies of a given place, it is suggested, could be focused by the mound, enabling interaction between a shaman-priest and the spirit world for the greater good of the community. This model of purpose and design seems to have directed the creation of Poverty Point as much as any other mound site.

Poverty Point

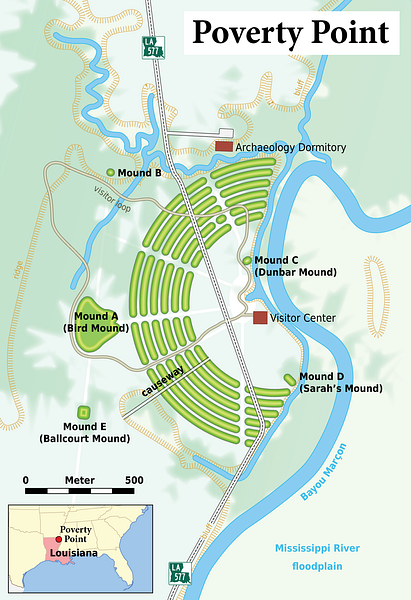

The concentric ridges at Poverty Point all were once platform mounds with homes on top built facing the ceremonial site of the plaza and Mound C. The energies of the homes, therefore, were directed toward the central plaza where rituals were performed and games played and the city was designed this way, perhaps, as an architectural engagement in reciprocity with the spirit world as the energies generated on the plaza would be directed toward the homes. The placement of the other mounds may have been intended to contain these energies in a kind of square. Behind the concentric ridges, which are separated at intervals by gullies, rises the tallest mound, Mound A, with Mound B to the north, Mound E to the south, and Mound D in front of the southeast edge of the ridges near the plaza. A sixth mound, Mound F, built later than the others, rises to the northeast of the ridges.

Mound A is thought to have originally been constructed in the shape of a giant bird which, if so, was most likely the totemic animal of the people. The mound was built quickly in under three months and may have served as the central energy point for rituals before Mound C was constructed. It is also possible that both mounds were used in concert with each other or, as at Cahokia, that Mound A was reserved for private rituals out of the public eye while Mound C was for communal celebrations.

The mounds vary in width and height throughout the site while the ridges are thought to have once been of uniform height. Today, the ridges vary from less than a foot to six feet and have been damaged through agricultural use. The dimensions of the mounds are:

- Mound A: 72 feet (22 m) high and 705x660 feet (215x200 m) at the base

- Mound B: 21 feet (6.5 m) high and 180 feet (55 m) at the base

- Mound C: 6.5 feet (2 m) high on a base 260 feet (80 m) long

- Mound D: 4 feet (1.2 m) high and 100 ft (30 m) at the base

- Mound E: 13 feet (4 m) high and 360x295 feet (110x90 m) at the base

- Mound F: 5 feet (1.5 m) high and 80X100 feet (24x30 m) at the base

Two other mounds are located near the site – Jackson Mound and Motley Mound respectively – both damaged. Jackson Mound was purposefully damaged by the landowner who was not interested in having his property become an archaeological site.

Poverty Point was built in stages over many generations and, unlike the people at Watson Brake, the Poverty Point citizens engaged in long-distance trade which supplied them with materials, like stone and copper, which was unavailable locally. Artifacts such as stone projectile points and various copper artifacts were made with materials imported from areas such as the Tennessee River Valley and the Great Lakes region of modern-day New York.

The inhabitants produced their goods on-site from the raw materials they received in trade and certain sections of the C-shaped ridges were dedicated to the manufacture of various ceramics, tools, and weapons. As noted, the C-shaped ridges are all aligned toward the central plaza which would have been the site of communal gatherings, religious rituals, and sporting events. Scholar Elodie Pritchartt writes:

At the center of the site is a plaza that covers about thirty-seven acres and is believed to have been used for ceremonies, rituals, dances, games, and other activities. On the western side of the plaza, archaeologists have discovered several deep holes arranged incircles of various sizes; they believe the holes held long poles, possibly serving as calendar markers. (3)

It is quite likely the archaeologists are correct in that solar calendars matching the pattern of holes at Poverty Point have been found at other mound sites, notably Cahokia. The lack of more evidence of a calendar like Cahokia’s Woodhenge of 48 posts encircling a central post is thought to be due to the extensive agricultural use of the land at Poverty Point by later European immigrants and American farmers which is also thought to account for the scarcity of evidence for the residences on the ridges.

The city flourished through 1100 BCE, but the population seems to have declined after this time and the city was abandoned sometime before c. 500 BCE. No one knows why the people left Poverty Point any more than why others left the many sites abandoned across the continent, but it is thought that climate change, affecting migration patterns, as well as flooding could have contributed to problems the people were already experiencing, overpopulation most likely being one of the major challenges. As the people subsisted by hunting, fishing, and gathering edible plants, changes in climate and migration were probably the major contributing factors encouraging people to relocate.

Discovery & Excavation

The site was later repopulated by another culture who had already left the area when it was discovered by an American businessman, Jacob Walter, in the 1830’s who stumbled upon it while searching the region for a lead mine. Walter identified the site as an “Indian town” and noted many artifacts strewn about and Mound A but as exploration of mound sites was not his main concern, he went on his way.

The land was purchased by one Phillip Guier of Kentucky in 1843 as a farm and he moved there with his wife, Sarah (who is buried in Mound D, also known as Sarah’s Mound). The plantation was known as Poverty Point by 1851, possibly named for a place near the Guier’s home in Kentucky. Guier was also uninterested in the site as a former Native American city and did not recognize the ridges as anything more than small hills when he had them plowed and planted with crops. Walter’s report did not come to public attention until after the first published account came out in 1873 and, by then, the land had been extensively farmed for decades.

It was not until the early 20th century that scholars and archaeologists began to take an interest in the site and in 1913 C.B. Moore arrived to begin excavations. Moore was a Harvard graduate and amateur archaeologist who financed his own expeditions from the fortune his family made in the paper business. He was especially interested in Native American mound sites, visiting a number of them and spearheading the work that brought attention to sites like Moundville and Poverty Point. Moore, and those who came after him, failed to recognize the scope and complexity of the site – and with good reason – because it could only be fully understood from an aerial view unavailable to them. Pritchartt writes:

While the mounds and artifacts at the site were well known, it wasn’t until 1953, when the discovery of a twenty-year old serial photograph revealed six concentric ridges in the shape of semicircles surrounding an open plaza, that people realized a significant treasure lay there. The man-made structure is so large it defies recognition from the ground and reveals evidence of a highly developed, ancient American culture. (1)

The attention then given to the site led to its declaration as a National Monument in 1960 and a National Historic Landmark in 1962. By 1972, the State of Louisiana had purchased 400 acres of the site and opened it to the public as a park with an interpretative museum and walkways. Interest in the site only grew afterwards and in 2014 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Conclusion

Poverty Point continues to fascinate and draw people from all over the world to learn more about the Native American culture that built it. The park is among the most popular tourist attractions in the area for many reasons, but the historical importance of the site is a major contributing factor. Pritchartt notes:

Before its discovery, the Middle East was considered the cradle of civilization. But at nearly the same time as the pyramids were being built in Egypt, people in the New World were building cities, establishing trade routes that crossed thousands of miles, and creating a complex society in an age in the New World that predated agriculture. Hunter-gatherers, previously considered by archaeologists and anthropologists not to have a complex enough social structure to pull off monumental engineering, were leaving their mark on history in a spectacular fashion. (1)

Although the so-called “Middle East” is still considered the cradle of civilization, it is now recognized that Native Americans were creating their own in the Americas. Visitors to the park today are able to experience their feats of engineering and city-planning first-hand through access to the mounds, ridges, and plaza as well as the many artifacts on exhibit in the museum. Although presently restricted by the Covid-19 virus, Poverty Point hopes to fully open again in the near future to provide this same experience to many more visitors in the coming years.