The Powhatan Confederacy (c. 1570-1646 or 1677) was a political, social, and martial entity of over 30 Algonquian-speaking Native American tribes of the region of modern-day Virginia, Maryland, and part of North Carolina, USA formed under the leadership of Wahunsenacah Chief Powhatan (l. c. 1547-c. 1618). These tribes are best known in history for the Anglo-Powhatan Wars of 1610-1646.

The tribes’ economy was based on agriculture and trade as well as prizes taken in battle from other native groups outside of the confederacy. Each tribe had its own chief (known as a weroance for males and a weroansqua for females), and they knew their land by the name Tsenacommacah (densely inhabited land), which they treated with respect as a living entity.

Each weroance was subject to Wahunsenacah of the Powhatans and paid him tribute which was redistributed throughout the confederacy to ensure proper food supplies for all. The confederacy maintained the matrilineal model of the individual tribes in which one’s family name and status was passed down from the mother’s bloodline, and women played important roles in government, finance, and food production.

The various tribes had lived as separate entities in the region for over 12,000 years before they were formed into a confederacy by Wahunsenacah. In 1607, the English established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia and this proved to be the beginning of the end for the Powhatan Confederacy. European diseases, to which the natives had no immunity, killed many, the Anglo-Powhatan Wars killed many others, and survivors were relocated to reservations and then removed further from their ancestral lands by the Treaty of 1646 and the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677.

One of these two dates is usually given for the official end of the confederacy, but their use depends on what one is emphasizing. The 1646 treaty dissolved the confederacy but allowed the indigenous people some of their former rights while the 1677 treaty completely ended Native American autonomy in the region. In the present day, only the Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes still retain their 17th-century reservation rights.

Wahunsenacah Founds Confederacy

Wahunsenacah inherited his position as chief from his mother who would have been a powerful member of the Powhatan tribe, perhaps even its weroansqua, and the responsibility for governance over six tribes:

- Appamattuck

- Arrohateck

- Chiskiack

- Mattaponi

- Pamunkey

- Powhatan

The Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee), who controlled the land from modern-day Canada down through Virginia, had been formed sometime in the 12th century and become a powerful political and military presence through their union of formerly warring tribes. Their example may have inspired Wahunsenacah to do the same. The tribes in and around Tsenacommacah frequently fought each other and the Iroquois also presented a significant threat.

Beginning with his six tribes, Wahunsenacah expanded his kingdom from his village of Werowocomoco (near modern-day Richmond, Virginia) throughout the region by bringing other tribes under his control. He accomplished this through attacks on other tribes which killed their chief and elders, later replacing these with Wahunsenacah’s sons, trusted family members, or responsible members of the confederacy. He also used diplomacy, making clear to a tribal chief the benefits of joining him, and bribery by way of offering certain incentives. By 1607, he had over 30 tribes as members of his confederacy.

Wahunsenacah kept peace between the tribes of the confederacy by organizing large-scale hunting expeditions each winter that sent his warriors toward the interior where they were encouraged to attack non-member tribes (especially those of the Iroquois Confederacy), take scalps, and bring back prisoners. The need for a young man to prove himself a warrior in battle was thereby met and tribal honor and prestige maintained through military victory.

Government & Spirituality

Wahunsenacah organized a cohesive system of government which depended on each individual understanding his or her place and behaving responsibly. Wahunsenacah was the Mamanatowick (Great Chief), and below him was a Peace Chief who handled domestic affairs and a War Chief responsible for military actions against others. Decisions were made for the confederacy as a whole by Wahunsenacah in consultation with his sages/counselors which numbered at least seven although later English accounts give the number at 14 or 20.

Each tribe of the confederacy followed this same model. The people paid tribute to the local chief who passed on what was owed to Wahunsenacah. A system was in place whereby the tribute would then be dispersed to all of the tribes according to their need. A certain amount was stored as surplus against poor harvests and lean times. The Powhatan government operated efficiently to maintain unity and meet the goals Wahunsenacah had in mind in bringing the tribes together:

- Peace through common interest, ending intertribal warfare

- Protection against other tribes, primarily the Iroquois Confederacy

- Protection of the resources and land of Tsenacommacah

- Ensuring an adequate food and clothing supply for all the people

- Honoring the land and the deities who had provided them with a home

To the tribes of the confederacy, as with all Native American nations, the land had been placed in their care by higher powers and it was their responsibility to keep that trust and honor the land. Scholar Joseph Eppes Brown comments:

Many tribes believe in the sustaining power of the land. Indeed, according to most Native American traditions, land is alive. Every particular form of the land is experienced as the locus of qualitatively different spiritual beings. Their presence sanctifies and gives meaning to the land in all its details and contours. These spirits also give meaning to the lives of the people who cannot conceive of themselves apart from the land. The recognition of a multitude of spirits does not preclude all of these spirits from coming together in one unitary principle. Like the spokes of a wheel, the spirits meet at the center in what some tribes refer to as the Great Mysterious or the Creator. (24)

For the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, the Creator was Ahone from whom all life flowed and order was maintained. Ahone caused the sun to rise in the morning and the crops to grow, brought life, and took life away. Ahone had a twin, Oke, who served the individual needs of the people because Ahone had enough responsibilities already with the maintenance of the world. The people would pray and sacrifice to Oke who would report their good or bad deeds to Ahone, and the tribe would then prosper or suffer accordingly. The care of the land was intimately tied to the recognition of a world imbued with spirits and so all of nature had to be treated with respect.

Agriculture & Daily Life

This understanding is seen in the agricultural practices and daily life of the tribes. The people of Tsenacommacah had been nomadic prior to the 16th century and, by the time of the Powhatan Confederacy, were semi-nomadic with some permanent villages and others established as seasonal communities. Scholar Rick Sapp describes their relationship with the land and agricultural/hunting practices:

They cleared fields by felling, girdling, or firing trees at the base and then setting fire to the slash and stumps. A site became unusable when soil productivity declined and local fish and game such as buffalo (which migrated into this area before 1400) were depleted. The bands then moved on. In every new location, the people used fire to clear virgin land. (290)

Once the fields were cleared, the women were responsible for planting the staple crops of corn, beans, and squash (the Three Sisters), maintaining, and harvesting them. Thanks were given to the spirits of the place as well as the twin gods for providing the people with sustenance and crop rotation was observed to allow the earth to replenish itself. The earth, as noted by Brown, was thought to be alive and would speak to the people and let them know its needs. The people, in turn, would speak to the earth, the trees, and the crops, explaining their needs and encouraging growth and health.

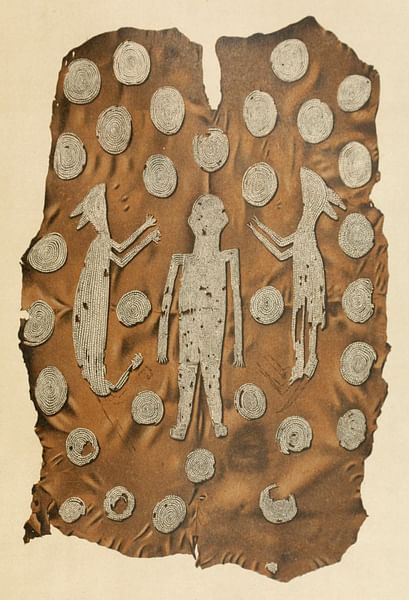

Women not only cared for the crops but were also responsible for building homes and managing a tribe’s finances. Homes, temples, and community structures were all built the same way by bending saplings over to form an upside-down U, anchoring the top to the ground, and covering the structure with woven reed mats, leaving a hole at the top to draw smoke from the hearth fire. A Powhatan building was similar to those of northern tribes of the North American eastern seaboard and was known as a longhouse (a yehakin); the teepee, so often depicted in colonial and later art concerning Native Americans was not used by the Powhatan. Even with seasonal hunting communities, the women would go out before the men and build them shelters along the same lines as permanent settlements.

The men were responsible for hunting, fishing, carrying out orders from the chief, and waging war. Girls learned the domestic skills expected of women, and boys were raised to be warriors or, if they showed certain abilities or certain signs presided over their birth, shamans (known as sachems). A day’s work began after sunrise – which was observed with a ritual of gratitude – and ended after sunset. An evening’s entertainment would have included storytelling, music, and dance.

Men were also given the task of making canoes (quintans) by felling trees, setting a small fire in the center of the log, surrounded by mud to contain it, and then scraping out the charred wood to form a hollow. They continued this procedure until the quintan was finished. The size of the quintan was dictated by the size of the tree used. Some, such as those used for hunting, trade, or war parties, were up to 50 feet (15 m) long and could carry as many as 40 men. The canoes were rowed with paddles or moved by poles and could travel quickly up- or downstream.

Women often used the canoes in trade or foraging expeditions. Women traded foodstuffs, skins, and furs with other tribes and were also responsible for the manufacture of wampum, polished shells strung together to form a belt or sash which usually told a story and served as currency. The central form of currency is thought to have been ohanoak (also given as roanoke which provided the place- name for the English Roanoke Colony as ohanoak was produced in that area). Ohanoak was polished beads or shells of different colors which were used to make wampum but could serve as currency on their own or strung together in a length but not intricately woven as with wampum. The tribes would later trade wampum with the English settlers and sent wampum of great value as gifts to English monarchs as an expression of friendship and peace.

Jamestown & the English

The English first made contact with the Virginia natives when they established the Roanoke Colony (in 1585 and again in 1587) which failed by 1590, primarily because of the behavior of the colonists toward the Native Americans. They tried again in 1607 and established the Jamestown Colony which would have also failed if Wahunsenacah had not ordered his people to provide the immigrants with food and supplies. Between 1607-1609, the Powhatan tribes endured continual theft of their goods and foodstuffs by starving colonists who could not manage to fend for themselves. Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) encouraged some measure of productivity in the settlers, but his efforts were not enough since more and then even more colonists kept arriving.

The famous account of John Smith’s capture by the Powhatans and being saved from execution by Wahunsenacah’s daughter Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617) has come to be understood by modern scholars as either a complete fabrication on Smith’s part or his misinterpretation of a death-and-rebirth ritual which made him a werowance of the English and part of the Powhatan Confederacy. Wahunsenacah had provided the English with food, not necessarily out of the goodness of his heart, but because he hoped they would be allies against other hostile tribes as well as the Spanish (who had colonized the West Indies, South and Central America throughout the 16th century) who raided the coasts for Native Americans they could kidnap and sell as slaves. The ritual Smith describes would have been enacted to symbolically “kill” him to his old life and allow him to be born again as a tribal chief, subject to the laws of the confederacy.

Smith clearly did not understand this and the Virginia Company of London – who had funded the Jamestown expedition – considered the Native Americans as just one more resource to exploit for profit. They ordered Smith and Captain Christopher Newport (l. 1561-1617) to make Wahunsenacah an English prince subject to King James I of England (r. 1603-1625) but Wahunsenacah either did not understand the coronation ritual they imposed on him or feigned ignorance; either way, he did not acknowledge James I’s supremacy and continued to regard himself as the autonomous ruler of his people.

After his coronation, the colonists were encouraged to think of the Powhatan tribes as subjects of the king who should willingly continue to supply them with food. Wahunsenacah had already provided them with plenty, however, and could not endanger his own food supply and his people for others who could not – or would not – provide for themselves. He cut relations with the colony in 1609 CE and ordered the settlers to remain within the walls of Jamestown. His warriors were given leave to kill any English found on Powhatan land.

Smith returned to England in October 1609, and the colonists starved. When a supply ship arrived in May 1610, the new governor Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) found only 60 people still alive in the colony. He ordered it abandoned and was bringing the survivors back to England when his ships were met by another carrying the aristocrat Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618) who ordered Gates to return to shore and re-establish Jamestown. This was the beginning of the end of the Powhatan Confederacy and Native American autonomy in the region.

Conclusion

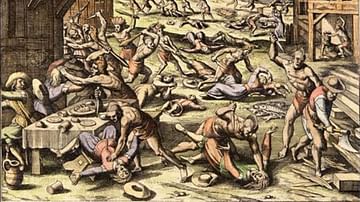

De La Warr engaged in a no-compromise policy in dealing with Wahunsenacah who, for his part, refused to be ordered about by a man he considered a commoner. The First Powhatan War (1610-1614) was a bloody series of conflicts, which only ended after Pocahontas was kidnapped in 1613, converted to Christianity, and married the wealthy tobacco farmer John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622) in 1614. Rolfe had arrived with Gates in May of 1610 carrying tobacco seeds which he experimented with to produce a sweet-tasting crop that drew easily in a pipe.

Rolfe’s tobacco saved Jamestown as its most lucrative cash crop but doomed the Native Americans of the area because, as the crop became more popular, more land was required for its cultivation. The Native Americans had long used tobacco for sacred rites, as a stimulant, and as medicine but the English turned it into a profitable commercial crop for recreational use and demanded more land as that use increased world-wide.

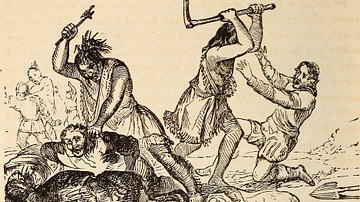

Pocahontas died in 1617 and Wahunsenacah c. 1618. His half-brother Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) then became Chief Powhatan and tried to drive the English out of his lands through the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626) but was defeated and lost more land. He tried again through the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646) which he also lost and in which he was captured, imprisoned, and then killed when he was shot in the back by his guard.

His successor, Necotowance (l. c. 1600-1649) signed the peace treaty of 1646 which dissolved the Powhatan Confederacy. Necotowance was succeeded by Totopotomoi (l. c. 1615-1656) who was only leader of two tribes, and his successor, his wife Cocacoeske (l. c. 1640-1686), had even less power and fewer lands.

In 1676, a wealthy landowner named Nathaniel Bacon (l. 1647-1676) rebelled against the policies of the Virginia governor William Berkeley (l. 1605-1677) and called for the extermination of the remaining Native Americans in the region or their removal. Bacon’s Rebellion failed when Bacon died of dysentery and the other leaders were hanged, but the Virginian government forced another agreement on the remaining tribes, the Treaty of Middle Plantation, in 1677, pushing the natives onto reservations.

The government also reinstated the headright system which encouraged colonists to take land from Native Americans in return for clear rights to 50 acres of whatever they were able to acquire. Through these means, as well as European diseases to which the natives had no immunity, the remaining tribes, once of the Powhatan Confederacy, were either killed, driven from the region, or pressed into reservations, and the immigrants turned Tsenacommacah, once densely inhabited by indigenous tribes, into the even more densely populated English colonies of Virginia and Maryland.